|

Taken from Indepedent.UK (May 04, 2001)

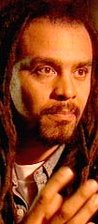

Michael Franti: And for my next rhetoric...

The work of Michael Franti retains its polemical edge, he

tells Fiona Sturges, but it's tempered with soul, even compassion

by Fiona Sturges

I am wandering around London's West End with Michael Franti, looking for a quiet place in which to talk. We've just been ejected from a basement bar in the Trocadero because of a fire drill. Hordes of backpackers hamper our progress on the pavement, and conversation is near-impossible with the sound of shrieking teenagers, car horns and unsynchronised bass grooves thumping from every shop. It's not a situation that a visiting rap dignitary likes to find himself in, but if Franti minds, he's not showing it. I am wandering around London's West End with Michael Franti, looking for a quiet place in which to talk. We've just been ejected from a basement bar in the Trocadero because of a fire drill. Hordes of backpackers hamper our progress on the pavement, and conversation is near-impossible with the sound of shrieking teenagers, car horns and unsynchronised bass grooves thumping from every shop. It's not a situation that a visiting rap dignitary likes to find himself in, but if Franti minds, he's not showing it.

These days he is the epitome of calm, extolling the virtues of love and compassion ­ not to say "the herb" ­ and walking around the streets barefoot. "My feet are pretty tough," he shouts over the crowd. "Chewing-gum's a problem, though."

We finally alight on a caf?, where the waitress visibly gasps at Franti's height. Before his career as a rapper and spokesperson for the disenfranchised, the six-foot-six Franti was making a living as a professional basketball player. He is still friends with Michael Jordan and the HIV-positive Magic Johnson, who partly inspired the song "Positive". But Franti opted instead for a career in consciousness-raising via the Beatnigs (signed to Jello Biafra's Alternative Tentacles label), the Disposable Heroes of Hiphoprisy and his most recent enterprise, Spearhead.

It has been four years since Spearhead's last record Chocolate Supahighway, yet, even in this short time, the industry has radically changed. Corporate mergers and rationalisations have given rise to some ruthless culling of artists. For the remaining musicians, the pressure is on to produce hits. When a new set of directors swept into Capitol two years ago, Franti was hauled in to shake hands with the president.

"He hadn't listened to any of my records at all," he growls, wrapping his long limbs around a bar stool. "He said, 'I really think you should do a song with Will Smith on his new album.' I was like, 'You don't really get it, do you?' "

It took nine months to extricate himself from his contract, since when he has set up his own label, Boo Boo Wax, on which he is releasing his third Spearhead album, Stay Human.

Politics has driven Franti since his Beatnigs and Disposable Heroes days. The heavy-duty rhetoric of songs such as "Television: the Drug of the Nation" and "Socio-Genetic Experiment" earned him a reputation as a hard-nosed polemicist as well as a gifted rapper. But since the inception of Spearhead, you might say that Franti has got in touch with his sensitive side. His songs have largely retained their political edge ­ issues of race and poverty still recur ­ yet they are tempered with the sound of R&B and soul music. While he insists that he is proud of his work with the Disposable Heroes, there is a hint of regret in his voice.

"I have always tried to enrage, enlighten and inspire people, but as a person I want to express a wide range of emotions," he says. "I'm not doing this just to be some kid's anger-management class because he's mad at his mom and he wants to go and slam-dance. I'm doing it because I need to express myself in my music."

Is he less angry than he used to be? "I don't think it's about being less angry," he ponders. "I think it's about becoming more centred and being able to deal with anger. When you look at Marvin Gaye, he was a really troubled soul, but when you listen to the album What's Going On?, it's clear he didn't just think, 'I'm pissed off so I'm gonna make an angry record.' He tried to make beauty out of that pain. Same thing with Bob Marley ­ no one would say that his records aren't militant, but when you listen to the rhythm and his voice, it's something that you would want to allow in."

Yet in Stay Human, he is revisiting the old days. It's as if the young, confrontational Franti has collaborated with his older, wiser self. The album displays the same rage and passion of the Disposable Heroes' d?but, Hypocrisy Is the Greatest Luxury ­ on "Rock the Nation", Franti is fiercely insistent, railing against American gun laws, globalisation and the power of the media. Yet the backdrop is unadulterated soul: during "Love'll Set Me Free", you could even mistake Franti for a young Curtis Mayfield.

The songs are constructed around a fictional broadcast on a community radio station, discussing the impending execution of a black activist on the eve of state elections. An interview is conducted with the state governor, played by Woody Harrelson, who in one instance declares, in a Southern twang: "It is our job to eliminate the people who do not function in our society."

Franti likes to call Stay Human a protest album. Over the past two years he has helped to organise anti-death-penalty benefits in his native San Francisco, which were originally intended to highlight the case of the jailed former Black Panther leader Mumia Abu-Jamal.

"There's been a number of high-profile cases in America concerning either death prisoners or people convicted of crimes that most of us feel they didn't do," he states. "Mumia Abu-Jamal just happens to be one of the major ones in California state. But I want to raise awareness for all those facing execution. I've been against the death penalty ever since I was a kid. I always thought: 'What if they've got the wrong guy, and what if that guy happens to be me or my child?' And as a black person in America, the threat of being wrongly accused or being a scapegoat is real."

Wrongful imprisonment is also a subject that is close to Harrelson, whose father is currently serving a double life sentence for the murder of a police officer.

"I first got involved with him in the marijuana movement," Franti remembers. "Woody is a long-time advocate of marijuana reform. He was reluctant at first to get involved with this album, as he was worried about the effects it might have on his father's case. But like me, he knows that being reactionary doesn't lead down a positive path. It's all about the perpetuation of violence; I see it in the community where I live. All around the neighbourhood you have these balloons and flowers laid out where people have been shot. I don't think it's right to kill people in that situation. Neither do I think it's right for governments to wage war on individuals, no matter what they've done. Ultimately, violence begets violence."

Franti is no stranger to violence. Born in Oakland, California, to a white mother and a black father, he was put up for adoption when he was still a baby. His foster father was an alcoholic and used to "take out his frustrations" on his son.

"He stopped drinking when I was 17 but he never left his tensions behind," he confides. "Two years ago he had a stroke and he became a different person. He came to me and said he was sorry for the things that happened when I was a kid."

Franti settled in San Francisco when he was 18 and has been there ever since. Now he has kids of his own ­ one is two; the other 14 ­ and is trying to teach them about tolerance and compassion. "San Francisco's a peninsula, so there is no place for it to grow out, yet the population keeps on growing. You learn to live with other cultures and people with other sexual preferences. If you can't, you're never going to get along there."

When I suggest that maybe it's hard to arouse feeling and political debate in music in such complacent times, Franti wags a finger at me and shakes his head. "I think of my own life. I get up in the morning; I might put in Thievery Corporation to start my day. Then I might listen to Rage Against the Machine when I'm driving in my car, and when I get home I might listen to some jazz and then go to a party and listen to Wu-Tang Clan. I figure that if music can affect my life that much in one day, then think how much effect it has on the masses of people over a lifetime."

'Stay Human' is out on Parlophone on Monday

|