| |

Taken from BeyondRace (Nov 14, 2008)

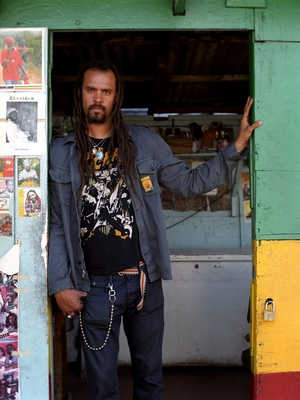

MICHAEL FRANTI & SPEARHEAD: REBEL MUSIC

by David Terra

Most people believe that to be revolutionary means to be violent, and that these (alleged) acts of violence are carried out by rebels. Michael Franti, front man for the politically charged rock/ reggae/ hip-hop hybrid Michael Franti & Spearhead, states that "to be a rebel today means to be in support of peace, in support of reconciliation, and in the power of the people." This proclamation also provides insight into the meaning of All Rebel Rockers, the group's sixth full-length album. Most people believe that to be revolutionary means to be violent, and that these (alleged) acts of violence are carried out by rebels. Michael Franti, front man for the politically charged rock/ reggae/ hip-hop hybrid Michael Franti & Spearhead, states that "to be a rebel today means to be in support of peace, in support of reconciliation, and in the power of the people." This proclamation also provides insight into the meaning of All Rebel Rockers, the group's sixth full-length album.

America's image of the rebel has varied over the years, ranging from the likes of James Dean, the cooler-than-thou ladies' man, to guerilla messiah Che Guevara. In 2008, Michael Franti is redefining what it means to be a rebel. No stranger to political activism, he has been using music to fight the power for over twenty years. His lyrical content spreads awareness about a myriad of relevant, yet controversial topics, such as the death penalty, gay rights, AIDS, police brutality, the environment, and most recently, the war in the Middle East.

The subject of the war has been an issue of significance for Franti over the last few years. At times, he has invited veterans of the Iraq War on stage, allowing them to voice their opinions, which usually involve a desire to see American troops safely returned home. In 2004, Franti decided to experience life in Iraq first hand. Traveling to the heart of Baghdad, armed with his guitar and a camera crew, he created the documentary I Know We're Not Alone, a film that offers a multi-dimensional perspective on the Iraqi people and the war that continues to devastate their country. According to Franti, "The most eye-opening thing for me was to meet with people on different sides and be able to see the humanity of these people. Although there's this war raging on, there's so many people who want normal things like safety and education."

I Know We're Not Alone captures Franti's essence as a humanitarian, as he conveys ideas of awareness and unification in an effort to eradicate the world's problems. His genteel demeanor brings smiles to Iraqi citizens who are physically and psychologically disenfranchised as a result of the war. As he walks down an Iraqi street cheerfully strumming his guitar, while chanting "habibi," Arabic for "my beloved friend," Franti attracts hordes of young children who sing along and stare in awe at the six and a half foot, dreadlocked mystery man. Being the only able bodied male in Iraq not holding a M-16 allowed for mostly peaceful exchanges, although there were moments of tension serving as very real reminders that he was in the middle of a war zone. Franti recalls, "There was one moment where this guy [who was pointing a gun at me] says, 'Will you stop playing guitar?' and I said, 'Yeah, when you take your finger off the trigger.'" It is this fearless optimism and his indefatigable spirit that has earned Franti legions of fans who idolize him as a prophet. Franti humbly dismisses the notion, considering his actions to be more aligned with the court jester, whom he personifies as "the funny guy with the hat who happens to make comments on the kingdom."

Franti, an enlightening performer with universal appeal, is probably the closest thing this generation has to the spirit of Bob Marley, who brought rebel music to the masses in the 1970s. Similar to Marley, Franti is a gifted poet with a keen ability for articulating honest, well informed criticisms about government and society. Back in the early '90s, his words were presented in a more confrontational way, allowing Franti to infiltrate the minds of late night MTV watchers with his seminal industrial punk and hardcore rap group, Disposable Heroes of Hiphopcrisy. Their hit single, "Television the Drug of the Nation," contains the hypnotic chorus of Franti chanting, "Television, the drug of a nation, breeding ignorance and feeding radiation" over a seductively raw sounding beat that combines a mesmerizing blend of electronic groove and funky rhythm. Renowned jazz musician Charlie Hunter, who played guitar in the Disposable Heroes, remembers Franti as "always having a natural talent for poetry and writing intelligent lyrics."

Hunter, who is best known for mind-blowing improvisations and deft skill at playing an eight-string guitar, befriended Franti while the two worked together at a guitar store in Berkley, California. Franti approached Hunter about joining a new project he was forming with Rono Tse, Franti's collaborator from his first band, The Beatnigs. Along with the electronic flavorings of Mark Pistel (Consolidated) and Jack Dangers (Meat Beat Manifesto), the Disposable Heroes scored a huge break when they were invited to tour the world on U2's Zoo TV tour. While giving Franti his first taste of an international platform, the tour awakened his desire to express himself in a more positive way through the art of storytelling. The result was the disbanding of the Disposable Heroes after only one album and the emergence of Spearhead.

From their debut, Spearhead has served as Franti's vehicle for expressing his uplifting ideology, while turning up the funk factor. In addition to biting social commentary promoting personal and political change through action, Franti's lyrics exude an introspective mentality, often conveying emotions of deep hurt and remorse. His talent for being able to effectively communicate feelings of struggling to overcome hard times is getting better with age, a notion which should be in contrast to his rising star power. Although it's hard to imagine Franti, an internationally renowned rock star, filmmaker, and activist, experiencing a difficult situation in years, he is human and deals with his share of trying times. In addition to losing a close friend to cancer during the past year, he recently broke up with a long time girlfriend. Franti reflects on the grieving process that you go through whenever somebody leaves and goes out of your life, "She's an artist and I'm an artist and her art takes her away and my art takes me away and it got to the point where we hardly ever saw each other. And that's the hardest part of my life, which is being away from my home."

Franti has always felt a strong connection to all the creative people who feel like outsiders in the world. Growing up in Davis, California, a conservative city about an hour northeast of San Francisco, Franti was raised by a white couple that adopted him. According to Franti, "The reason why my parents gave me up was because my mother is white and my father is black, and she felt her family would never accept their grandson." To make matters more difficult, Franti's adoptive father was a physically abusive alcoholic. A tumultuous home environment found Franti leaving Davis at an early age for the utopian vibe of San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury, where he first fell in love with live music. Although painful to discuss, Franti is reflective about the influence his upbringing continues to have on his development as an artist, "All of us have times when we feel like we don't belong. And I think to stress your individuality, and apply it to the interconnectedness of other people, is one of life's greatest ambitions." After earning an athletic scholarship to pursue his hoop dreams at the University of San Francisco, Franti eventually became disillusioned by the pressures and homophobia rampant in college sports, dropping out of school to pursue a career in music. The rest, as they say, is history.

While his early musical years were spent railing against the system, Franti has evolved to a place where he is more interested in using his voice as a means to unite and support. In recent times, his lyrics have become known for bumper sticker worthy slogans such as, "You can bomb the world to pieces, but you can't bomb it into peace." Equally as thought provoking as "Television the Drug of the Nation," yet more refined in its approach, he suggests a solution instead of just illuminating a problem. Franti attributes his lyrical evolution to getting involved with various grassroots organizations. One of the most relevant organizations Franti works with is Power to the Peaceful, a not-for-profit, non-partisan organization "dedicated to the promotion of cultural co-existence, non-violence and environmental sustainability through the arts and music." The organization is best known for its free annual festival, which originated in San Francisco and has recently held events in Africa and Brazil. Franti beams about the uniqueness of the festival's origins, "We were looking at what was happening with the amount of money spent on schools, versus the amount of money being spent on prisons. We wanted to say this is an emergency situation." Originally staged on September 11, 1999 and also on September 11, 2001, the meaning of the festival shifted away from being just about prisons after 9/11. According to Franti, the festival has grown to become about "the war, and giving the call to end all political violence and domestic violence….Everywhere we have a different theme, as long as it's happening in the local community." While his early musical years were spent railing against the system, Franti has evolved to a place where he is more interested in using his voice as a means to unite and support. In recent times, his lyrics have become known for bumper sticker worthy slogans such as, "You can bomb the world to pieces, but you can't bomb it into peace." Equally as thought provoking as "Television the Drug of the Nation," yet more refined in its approach, he suggests a solution instead of just illuminating a problem. Franti attributes his lyrical evolution to getting involved with various grassroots organizations. One of the most relevant organizations Franti works with is Power to the Peaceful, a not-for-profit, non-partisan organization "dedicated to the promotion of cultural co-existence, non-violence and environmental sustainability through the arts and music." The organization is best known for its free annual festival, which originated in San Francisco and has recently held events in Africa and Brazil. Franti beams about the uniqueness of the festival's origins, "We were looking at what was happening with the amount of money spent on schools, versus the amount of money being spent on prisons. We wanted to say this is an emergency situation." Originally staged on September 11, 1999 and also on September 11, 2001, the meaning of the festival shifted away from being just about prisons after 9/11. According to Franti, the festival has grown to become about "the war, and giving the call to end all political violence and domestic violence….Everywhere we have a different theme, as long as it's happening in the local community."

This enlightened attitude is evident on All Rebels Rockers, which Franti views as "a collection of songs for people who wake up and go, 'Man, I don't know if I can make it through the day. The weight of the world seems so much.'" The album is heavy on inspiration and chilled out reggae vibes, a direct result of recording in Kingston, Jamaica. To Franti, Jamaica is an ideal place to create and record because "it's like the meeting place between Europe, Africa, and North America…so the music there is the instruments of Europe, the rhythms of Africa, and the creativity of the United States."

Noteworthy throughout the album is the influence of riddim masters Sly Dunbar and Robbie Shakespeare, the all-star production team who has worked with a number of popular music's most influential artists during the past forty years, ranging from Bob Dylan to the Rolling Stones, and virtually every Jamaican reggae artist of significance. Franti first met Sly and Robbie in 2000, collaborating with them a handful of times over the years. Dunbar speaks fondly of their relationship, "Michael has been a longtime friend of ours...we'll keep on saying to him, 'If there's an album that people can only listen to, then you score one point. If there's an album that people listen to and dance to, then you score two points.' And I think you have to score two points." After having Sly and Robbie produce a handful of songs on 2006's Yell Fire!, Franti and crew returned to Jamaica to record All Rebels Rockers in its entirety, once again utilizing the guidance of the duo's musical expertise. It was through Sly and Robbie that Franti learned he could make reggae music. While he has been a fan of the genre for many years, Franti remembers thinking, "I never thought I could make reggae music…then I met Sly and Robbie, and they told me reggae is not a nationality. It's a rhythm."

While the soles of Franti's feet are worn from not wearing shoes, the desire to use his life and art as a catalyst to move people to revolutionary actions through peace is as strong as ever. Franti's usual post-performance routine involves making himself available to fans for hugs and well wishes, no matter how big the crowd, which, in recent times, is often well into the thousands. Franti's spirit and uplifting messages continue to grow more sincere over time, something he attributes to his maturation as an artist, "I think in the last five or six years, I've taken on more serious responsibility to be the best musical communicator I can be…I'm going to all these places and seeing these things so I can report back to the people and help create awakenings." While the future is still to be written, as long as he's armed with his guitar, Michael Franti will forever be a rebel.

|

|