|

Taken from Washington Post (March 16, 2007)

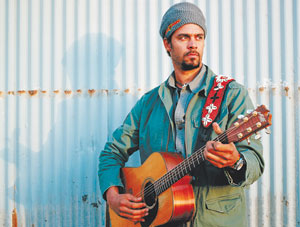

Franti, Raising The Alarm

by Richard Harrington, Washington Post Staff Writer

As musician, writer and now documentary filmmaker,

Michael Franti is a triple threat. |

With a concert tour to support a recent CD ("Yell Fire!") as well as a new book ("Food for the Masses: Michael Franti -- Portraits & Lyrics") and a documentary film ("I Know I'm Not Alone"), has Michael Franti become the King of All Media?

"I'm the underground Rupert Murdoch!" Franti says with a hearty laugh from his San Francisco studio, where he's preparing his next album and the launch of a Spearhead tour that lands at the 9:30 club Friday night.

Franti being Franti -- definitely not Murdoch -- "Yell Fire!" opens with a declamation: "A revolution never come with a warning / A revolution never sends you an omen / A revolution just arrive like the morning / Ring the alarm, we come to wake up the snoring."

Wake-up calls have been a constant in Franti's career, including in his mid-'80s quintet, the Beatnigs; his early '90s agit-hop ensemble, the Disposable Heroes of Hiphoprisy; and Spearhead, which dates to the mid-'90s. The sound has evolved and expanded from the Beatnigs' noisy industrial sound and Disposable Heroes' mix of hip-hop, rock and jazz to Spearhead's danceable swirl of hip-hop, funk, reggae and rock. But the center has always held: sharply crafted, socially and politically conscious lyrics addressing a wide range of topics, such as racism, poverty, hunger, the death penalty, corporate globalization and media manipulation. Always, there is a message of peace and global unity.

"When you have something you want to say, you need to say it," the always outspoken Franti says.

Franti's best-known song, the scathing denunciation of "Television, the Drug of the Nation," first appeared on the Beatnigs' 1988 EP, though the Disposable Heroes' updated version is better known.

"I rewrote the lyrics to reflect how during the Gulf War, cable and CNN started bringing us 24-hour war coverage in new high-tech and 'sanitized' ways," Franti says, describing "a method where it appeared as though no one was actually being killed. I could probably write another version today, and if I did it, it would be about Fox."

Okay, he's definitely not Rupert Murdoch.

After watching coverage of the current war in Iraq on television -- Franti is a critic of the medium, not a Luddite -- the musician did what few other critics have: He grabbed his acoustic guitar and, with a ragtag crew of eight and three digital video cameras, headed to Baghdad for a firsthand look at the human cost of war. He also made a side trip to Israel, visiting the West Bank and Gaza Strip to examine the long-term costs of war and occupation.

"I Know I'm Not Alone," which Franti produced and directed, uses songs from "Yell Fire!" In fact, Franti worked on both projects concurrently (they were released in July) in his San Francisco home. With an editing studio on one floor, a recording studio on another, Franti found himself immersed in the projects.

"It was really a catharsis for me," he admits, "because when I came back, I was so filled with deep, deep sadness and intense anger and rage, and I was trying to find a way to communicate that to other people without them turning their heads away. As I watched all the footage, it became a way for me to purge all that and put it into my songs."

Not that all the songs rage against the machine, though Franti does declare that "those who start wars never fight them / And those who fight wars never like them" and insists it's "Time to Go Home." But the album also includes the reggae ballad "One Step Closer to You," "Tolerance," "Hello Bonjour's" multilingual plea for global unity and the anthemic "I Know I'm Not Alone."

"When I came back, I thought I would write a whole bunch of songs that would, perhaps, point a finger at the president," Franti explains, "but something happened to me while I was over there. I saw that when we spent all our efforts trying to prove that we're right and convince another person that our side is the right side, and they're trying to do the same thing, we never reach the middle ground that leads to a lasting peace. That's been the biggest lesson for me, coming back to America and trying to communicate what I had seen to other people.

"I don't believe anymore in the politics of trying to convince somebody that my way is the right way. I believe in the politics that considers the other side, that listens to the other side. It's the key to what's happening in the Middle East, to the environment, to all of it."

Franti's journey began in May 2004, when he arrived at the Baghdad airport via Jordan, learning quickly how dangerous things were when the pilot of his small passenger plane explained that its spiraling descent at a 45-degree angle was necessary to reduce the chances of being hit by surface-to-air missiles or small-arms fire.

According to Franti: "As soon as you get on the ground, you look around the airport and see the holes in the field where missiles and rocket-propelled grenades have landed. The road leaving the airport and into the city used to be lined by palm trees, and every one of those trees has been chopped down to matchsticks. And you see where cars have gone off the road and blown up and are still sitting there. It's a really vivid thing."

How vivid?

"As we were leaving the airport, there were two cars that had just been blown up and were on fire, with bodies still in them, and soldiers all around pointing their weapons in ready position," he says. "We lifted our cameras to film it, and our driver slammed them down and said, 'You can't ever film anything around U.S. military operations, or they'll open fire on our vehicle.' That was an awakening."

Iraqi officials asked Franti the purpose of his visit and classified him as a tourist when he said, "To play guitar in the streets." So, was he there as a tourist or as a reporter?

"I felt maybe something in between," Franti says, "but mainly I felt like a troubadour, somebody who was just traveling and bringing music to people and then having conversations."

The towering Franti -- he's 6 feet 6 inches tall -- spent his time busking the streets of Baghdad and chatting with locals, learning how they made it through their daily lives under extraordinarily tough circumstances.

"When I was playing music on the street, people would come up and I would say, 'Tell me about your life here.' At first people were a little bit hesitant. But when they'd hear the music, they'd start to open up, and they would invite me to their homes, invite me into their cafes or whatever, and then they would really open up. And you'd see this passion: 'This is the moment we've been waiting for to tell our stories to the world.' It was through the power of music that would really open people's hearts up."

Even a simple vamp consisting of a single word, "habibi," an Arabic term of endearment along the lines of "my beloved friend": When Franti sang it, little kids and wary adults alike would dance and sing along to its momentary relief, he says.

"That's what I found as I was going around, that the people who were hit the hardest were the people who were most responsive to music. You could feel the pressure drop."

Franti also visited the Gaza Strip and Palestinian territories, speaking to refugees and Israeli soldiers and interviewing grieving mothers from both sides of the divide. He'd gone to Iraq to see the effects of a single year of occupation; the West Bank and Gaza Strip journey was to see what three generations of occupation had done to Palestinian society. Franti found "a lot more hopelessness and despair" there but also instigated some revealing dialogue between Palestinian farmers and Israeli soldiers.

"It really restored my faith that way, just seeing how simple it is to get people to stop and be quiet and listen to one another," Franti says.

It was natural that Franti gravitated to local performers, from street musicians and a Palestinian hip-hop crew to a collective of Israeli and Palestinian musicians and Iraqi metal band Black Scorpions, which not surprisingly had great difficulty finding instruments and accessories, sometimes using telephone wire for guitar strings.

Franti says he quickly recognized that nobody wanted to hear protest songs, or songs about the war, though he did play "Bomb the World" ("You can bomb the world to pieces, but you can't bomb it into peace") to a group of off-duty American soldiers in a Baghdad bar. Franti called that "the hardest show I'd ever done in my life" but also facilitated a party that brought some of those soldiers together with the Iraqis behind Radio Iraq, Baghdad's first independent radio station.

In the film, Franti says the trip "made me realize one very important thing, which is that I'm not on the side of the Americans, Iraqis, Israelis or Palestinians. I'm on the side of the peacemakers . . . whichever country they come from." He's still in touch with quite a few of the Iraqis in the film, "in e-mail touch, which is difficult in Iraq, and there's a lot of people in Israel and Palestine we still keep in touch with. The lead singer from the Black Scorpions now goes to school up in Victoria, B.C., and I've seen him several times -- he comes out to our shows."

Franti has written a companion paperback, "I Know I'm Not Alone: A Musician's Journey Through War and Occupation in Iraq, Palestine & Israel," and put together "Food for the Masses," a collection of lyrics and black-and-white portraits from his early years with the Beatnigs to Spearhead's CD "Everyone Deserves Music." It showcases why many place Franti in the hallowed tradition of Bob Marley, Marvin Gaye and Curtis Mayfield.

Besides copies of original handwritten lyrics, "Food for the Masses" includes a CD/DVD of unreleased live performances. Franti hopes the book will lead to a reconsideration of the breadth of his work and its evolution from militant passion to a more compassionate, personal bent.

"I've been known as a political artist," Franti concedes, "but if you go through the book and read the lyrics, there are songs about s.e.x, songs about food, songs about partying, songs about sadness, songs about love and songs about political things. I've always tried to express the full cycle of human experience."

Listen to an audio clip of Michael Franti and Spearhead

Appearing Friday at the 9:30 club

Next:"Probably the funkiest, most danceable record, but also the most raw sounding," Franti says. "I'm writing from little one-minute video clips that I take with my little still digital camera and edit together on my Mac. So I'll make the music first, put the images and then write from what the images are telling me. It's just been a different way of writing songs."

|