| |

Taken from PopMatters (Nov 6, 2006)

Dispatches from the front are in searing protest music

by Greg Kot, Chicago Tribune

With America immersed in an increasingly controversial war in Iraq, and soldiers coming home weekly in body bags, protest music is once again flourishing. In recent months, high-profile artists such as Neil Young, Pearl Jam, Bruce Springsteen, Paul Simon, Pink, Audioslave, the Flaming Lips and the Roots have addressed the conflict in songs or on entire albums. With America immersed in an increasingly controversial war in Iraq, and soldiers coming home weekly in body bags, protest music is once again flourishing. In recent months, high-profile artists such as Neil Young, Pearl Jam, Bruce Springsteen, Paul Simon, Pink, Audioslave, the Flaming Lips and the Roots have addressed the conflict in songs or on entire albums.

Most of that music comes from a second- and third-hand perspective, an outraged response to newscasts and media reports from overseas. But two recent albums break the mold. They address the consequences of war from a more personal vantage point; they’re musical bulletins from the front lines.

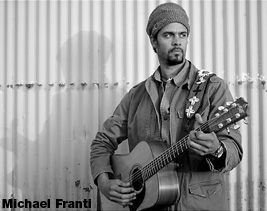

On the Refugee All Stars’ debut album, “Living Like a Refugee” (Anti), a ragtag group of musicians and singers who survived Sierra Leone’s 11-year civil war tells its story in song, an epic tale of slaughter, exile and redemption. Michael Franti and Spearhead’s “Yell Fire!” (Anti) chronicles Franti’s visits to Baghdad, Israel and occupied Palestine, armed with only an acoustic guitar and a video camera.

In addition, movies documenting these extraordinary journeys through what can only be described as hell on Earth have been released; “The Refugee All Stars Movie,” shot by fledgling filmmakers and musicians Zach Niles and Banker White, has been playing at festivals around the world, and Franti’s “I Know I’m Not Alone” (Anti) is now available on DVD. Both provide a powerful visual counterpoint to music that describes the human cost of war and celebrates the spirit of those who rise above their harsh surroundings.

“The Refugee All Stars Movie” depicts a world immersed in chaos, as tens of thousands died and 2 million fled a bloody civil war in the West African nation of Sierra Leone. These refugees spent the better part of a decade moving from camp to camp in neighboring Guinea. Along the way, a longtime musician from Freetown, Sierra Leone, named Reuben Koroma and his wife, Efuah Grace, started putting together a band that would eventually include 11 members. At first they had no instruments, but this didn’t deter Koroma from writing and performing songs that documented their experience. Eventually, they acquired guitars and an amplifier through the aid of a Canadian relief agency, and they fashioned drums out of cans and hubcaps.

In 1994, Koroma’s father was hacked to death by machete-wielding rebels, and his mother died while trying to escape. Rebels chopped off the arm of one of his future bandmates, Abdul Rahim Kamara, and cut off the hand of another, Mohamed Bangura, after forcing him to kill his child. After fleeing Freetown in 1999, Koroma and Grace drifted through five camps. Music saved his life, he says.

“I was highly traumatized,” Koroma says in a phone interview from Guinea, where he was awaiting visas that would allow him and the rest of the Refugee All Stars to tour North America, including a Nov. 4 date at Martyrs. “Grace is an experienced woman, and she could handle a husband who has such a problem. But sometimes you have something painful in your mind, and there is no way to express it. I was able to express that pain in songs.”

“Ya N’Digba” is a tribute to his late mother, and “Akera Ka Abonshor” is addressed to his family, encouraging them to stay unified in the face of turmoil. Other songs describe the life of a refugee, the yearning for home, and the greed of politicians.

“Sometimes when a man is facing difficulty, that is the best time for him to write,” Koroma says. “Most of the songs on the album were written in the camps. I was very much frustrated for my siblings, my children, my whole country. I was separated from everything I loved. Music was a way of comforting myself, a form of therapy and treatment. It was music that healed me, reformed me, made me normal again.”

In turn, Koroma’s music and the Refugee All Stars become the social center of camp life. Though written under dire circumstances, the music is joyous, upbeat, a blend of West African folk, pop and Caribbean reggae known as goombay. It is built on simple melodies and urgent call-and-response vocals sung in English, a style of music the 42-year-old Koroma had been playing since the mid-’80s.

“I had no plan to ever make an album,” Koroma says. “I kept the music I made for myself.” But the film crew recorded some of the All Stars’ music while making their documentary, and once the group returned home, it set out to make a record. They recorded the bulk of “Living Like a Refugee” in a windowless concrete bunker in the Freetown ghetto, an area where, Koroma says, “no one would expect that great things would come.”

“Living Like a Refugee” cuts through all the politics and sloganeering that can weigh down protest music to deliver a moving testament about the healing power of music. The cross-generational blend of voices, ranging from a teenage rapper (Alhaji Jeffrey Kamara, aka “Black Nature") to a guitarist in his 50s (Francis John Langba), is a stunning affirmation of resilience and hope in the face of debilitating odds.

Franti found that same spirit as he ventured to the Middle East and Iraq. A longtime activist who has folded political commentary into the agit-rap of the Beatnigs and Disposable Heroes of Hiphoprisy before forming the soul-funk band Spearhead, Franti is a San Francisco-based musician whose trip grew out of frustration with news coverage of the conflicts overseas. Franti found that same spirit as he ventured to the Middle East and Iraq. A longtime activist who has folded political commentary into the agit-rap of the Beatnigs and Disposable Heroes of Hiphoprisy before forming the soul-funk band Spearhead, Franti is a San Francisco-based musician whose trip grew out of frustration with news coverage of the conflicts overseas.

“Every night I’d be watching the news and I’d hear some general or politician explaining the economic cost of war, the machinery of war, but I never saw anyone speaking about the human cost of war,” he says in an interview.

He almost got more than he bargained for. In the documentary, bombs go off in the near distance as he interviews a U.S. soldier in Baghdad. While walking the crowded streets of Hebron in the occupied West Bank in Palestine, shots ring out and civilians scatter.

“You feel you could be shot or killed at any time,” he says. “I would hear gunfire or bombs going off and I would panic. The people in Hebron would tell me, `Walk, don’t run.’ In Baghdad, they can tell you what kind of bomb just hit and how far away it is. They get accustomed to the daily violence, but they don’t get comfortable with it.”

Franti said he expected to return from these war zones with fodder for “14 songs about how upset I am with the U.S. administration.” Instead, he gravitated toward songs with a more empathetic perspective. Music unlocked doors for him and defused potentially violent situations. Whatever suspicions the war-zone denizens might’ve harbored about the 6-foot-6-inch dreadlocked stranger in their midst melted away into smiling, hand-clapping celebrations when he began strumming his guitar. Similarly, Franti’s camera focused on local musicians _ folk singers, rappers, metal bands—playing with a joy that flew in the face of their circumstances.

“The guitar saved our ass a little bit,” Franti says with a chuckle. “The goddess of music was at work, and not just for my music. The music these people made, whether it was soldiers at a checkpoint beating on top of a Humvee singing Bob Marley songs or (Iraqi youths) playing heavy metal in a bombed-out basement, helped these people get through incredibly difficult situations.”

The experience shifted Franti’s perspective on what kind of album “Yell Fire!” would become. Blending folk songs with reggae grooves supplied by the Jamaican rhythm section of Sly Dunbar and Robbie Shakespeare, Franti has made a rare breed of protest album. It not only encourages dancing, it has a sense of humor. “I like my bass loudy, loudy louder,” Franti exults, “ ... the one sound louder than a bomb.”

Underlying both the Refugee All Stars’ “Living Like a Refugee” and Franti’s “Yell Fire!” is the tacit acknowledgement that the most precious and fragile commodity in any war is the human spirit. As long as that survives, these albums proclaim, no people can be defeated.

“When you think about tough times, there are times when you want to acknowledge what is happening politically in the world, there are times when you want to write songs that move hearts and bring a tear to the eye, and there are times when you need to move on, and make music that will inspire people,” Franti says. “Even though what I just watched on the news makes me feel like hell, when I get up in the morning I want to put on a record that makes me feel like the world is still worth fighting for. It’s not about changing minds. It’s about opening them.”

© 2006, Chicago Tribune.

|

|