| |

Taken from PopMatters (28 July 2006)

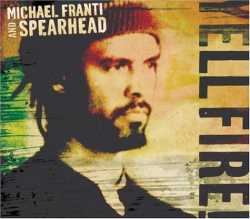

Michael Franti & Spearhead: Yell Fire!

(Boo Boo Wax)

PopMatters Music Review

by Dan Raper

"Searing" is probably the one adjective that's be most liberally applied to Michael Franti's music over the course of his long career. Critics with longer memories than mine point to Franti's violent work with the Disposable Heroes of Hiphoprisy as a way of putting in stark relief the Spearhead's present-day vibe, but in reality, Franti's last couple albums with the group have shown a continued trend away from this militant activism. Franti now preaches peace by lamenting the lives wrecked by social ills. That's all well and good, but he's chosen a somewhat surprising soundtrack on his latest album, Yell Fire!: the contained and upbeat sounds of reggae and U2 guitars. "Searing" is probably the one adjective that's be most liberally applied to Michael Franti's music over the course of his long career. Critics with longer memories than mine point to Franti's violent work with the Disposable Heroes of Hiphoprisy as a way of putting in stark relief the Spearhead's present-day vibe, but in reality, Franti's last couple albums with the group have shown a continued trend away from this militant activism. Franti now preaches peace by lamenting the lives wrecked by social ills. That's all well and good, but he's chosen a somewhat surprising soundtrack on his latest album, Yell Fire!: the contained and upbeat sounds of reggae and U2 guitars.

2001's Stay Human is still a vital album-it teaches us insulated iPodders what it means like to be discriminated against, why rage is justified; it motivates all of us through both incendiary calls-to-arms and celebratory positivity; and you won't find a better protest song than "Rock the Nation", or a better soul celebration than "Sometimes". And when was there more weary horror in a singer's voice than on "Oh My God"? It's Franti's best work with Spearhead. Everyone Deserves Music, the group's 2003 follow-up, largely ditched the vitriol to lay out a more positive message of acceptance and spiritual harmony. Even the outcries "We Don't Stop" and "Bomb the World" are full of a vitality and, yes, happiness. As a whole, the album wasn't quite as successful; the happiness felt a little forced.

Turns out Everyone Deserves Music was an indication of the direction Franti's thinking was headed, because Yell Fire! isn't as dark as you'd expect for an album born out of Franti's 2004 trip to Baghdad, the West Bank and Gaza Strip. It's understandable that Franti could come to the conclusion that "people don't want to hear songs against the war. They want to hear songs about connection to people, and songs about love and life."

Now, if you don't like your hip-hop preachy, Franti's music will most likely never have appealed to you. So it may come as a welcome surprise to hear of this resolution, above. Further, you may think: the best recent anti-war song is "I Was Only 19" by Australian hip-hop group the Herd, because it's all emotion, drained of the righteous outrage (so that when that line "I can still hear Frank, a screaming mess of bleeding flesh" drops, it's all the more powerful). Then you may wonder if Yell Fire! can emulate that. Unfortunately, it falls short. "Yell Fire!", the prime example of agit-hop on the disc, takes on Iraq, corporate greed, pharmaceutical marketing and environmental policies, as well as repping Rasta pioneer Peter Tosh, within the space of a few minutes. Behind Franti's booming voice, a singing guitar riff and ska accompaniment mark the album's most fiery, but still catchy, cut: still, its impact is greatest intellectually, not emotionally.

That's a problem with Michael Franti's music, when it comes down to it. His songs are pleasant but derivative, and never rise above being an appropriate accompaniment for his words. So that when he tries to drain the words of their fire, to create songs "about love and life", he slips down into this stale musical vocabulary that relies on clichés and tricks to impress.

There will always be something uplifting, something horrific, and something silly on a Spearhead album, and Yell Fire! is no different. Pink guests with backup vocals on "One Step Closer to You" (one step up the ladder of respectability for that choice, Pink), and shows remarkable restraint, daintily echoing the chorus and some lines in the verse. The slow reggae ballad explodes into a celebratory chorus before-yes, they do-the whole song gets the one-tone-up transposition treatment. Shameless! Similarly, "Hello Bonjour" is too incessantly happy, and the chorus is hard to swallow (in particular, the repeated "wa" at the end of "konnichiwa"). Soul music (the inspiration for "Sometimes") may work better to communicate these feelings than reggae, which can sound empty, or worse, smoke-addled. And an overdose of sappiness is so easy to ridicule; as on "Tolerance", Franti recalls a little too closely David Brent's song "Spaceman":

Spaceman came down to answer some things

The world gathered round from paupers to kings

"I'll answer your questions, I'll answer them true

I'll show you the way, you know what to do"

"Who is wrong and who is right --

Yellow, brown, black or white?"

Spaceman he answered, "You no longer mind

I've opened your eyes-you're now colourblind"

The best songs are still worth a listen, though. You can hear Franti's awakening as "Time to Go Home" progresses: opening with a simple reggae beat infused with soul and some gently-placed surf chords, Franti's voice is familiarly distraught, carrying the weight of experience. And by the song's mid-point, when the texture has expanded and his voice filled out, the classic "How many people..." repetition recalls "Blowin' in the Wind", entirely re-contextualised. "Light Up Ya Lighter" is an entirely successful melding of a call-to-arms style and he band's adopted reggae mode, using satire and an upbeat chorus to convey the experience of being a soldier abandoned by your government.

It seems a familiar critical refrain at this point that Franti doesn't get the recognition he deserves; why, for instance, he's a marginal figure (at best) in his home country. It seems to give credence to his posture of hated-by-the-system, but it may be more a consequence of the fact that he's now making music (forget the message) that's decidedly unfashionable, and-why beat around the bush-a tad dull. Slipping into genre stereotypes should sound a warning bell for the artist's career, and it's a shame, because Michael Franti's message, even if it is overly idealistic, should be welcomed when war is an unfortunate reality.

|

|