| |

Taken from Paste Magazine (Apr 22, 2024)

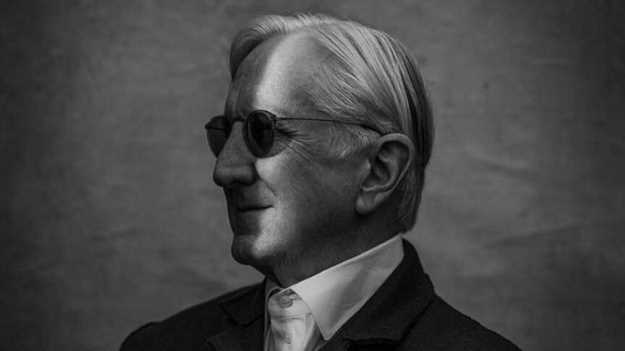

T Bone Burnett Finds 'The Other Side'

The legendary producer discusses his inspirations and the all-star cast of musicians featured on his first solo album in 16 years.

by Geoffrey Himes

Photo by Dan Winters |

T Bone Burnett is best known for producing such classic albums as Los Lobos' How Will the Wolf Survive, Elvis Costello's King of America, Robert Plant & Alison Krauss's Raising Sand and the soundtrack for O Brother, Where Art Thou? But he is now reviving his own fruitful-if not sporadic-career with his first solo album in 16 years: The Other Side. If it's less brittle and biting than much of his previous work, it's no less skeptical about the state of the modern world.

"We live on a hostile planet," T Bone Burnett says over Zoom from the patio of a Los Angeles hotel, "and life has always been outrageous. That hasn't changed. What has changed is the tone of my response to that world. Before my tone was too strict, too hard, not loving enough for what I care about now. I asked myself, 'Do I want to be in the room with that tone?' The answer was no." When he uses the term "tone," Burnett means more than just the timbre or texture of the music. After a note is first struck, it hangs in the air, either ringing with sympathetic overtones or clanging with discordant vibrations. The one unconsciously evokes conciliation in the listener, while the other suggests confrontation. Either way, it creates an emotional temperature for the song. There's a time and place for each, and in the past Burnett has often chosen the latter, but for his new album, he adopted a friendlier tone.

"I'm too old to be an angry young man," he explains. "I'm 76. It's not that I believe in something different; it's that I believe in more things. Hopefully I've gotten smarter in my old age. I've had incredible experiences in my life, and all that experience goes into these songs. I feel I've come into a clearing where I don't have to save myself or anyone else, where the songs don't need to be anything but beautiful.

"Tone is underneath everything," Burnett continues. "Authors, filmmakers, painters all talk about the tone of their work. In the human voice, there can be a kind tone and an angry tone; people can say one thing with their words and another thing with their tone. When you're reading there's a tone underneath the words. That's what poetry is all about; it takes you into the mystery of life. That's tone; that's music. It's clear to me that we invented spoken language to be able to lie, because when you sing, the tone lets everyone know what you mean."

Burnett's use of tone is evident on the new song "(I'm Gonna Get Over This) Some Day." Over the drummer-less, clickety-clack train beat reminiscent of Johnny Cash & the Tennessee Two, there's a bouncy, friendly dobro lick from Colin Linden and a fence-mending vocal from Burnett. "I don't want to be the judge, and I don't want to hold a grudge," he sings. "I'm gonna get over this someday; I might as well get over it now." Cash's daughter Rosanne adds a humming harmony, and the song's healing, hymn-like quality is complete. "That was like a song by Don Gibson, a 1950s country songwriter I like a lot," Burnett explains. "And the arrangement had that Tennessee Two sound. To me, Johnny Cash is like Walt Whitman, an American giant. I like that early rockabilly period before they had drums, and there are no drums anywhere on this record. Drums take up a lot of sonic space-they reach your ears very quickly-and I wanted a lot of room on this album."

T Bone Burnett had produced the Grammy-winning soundtrack for the 2005 Johnny Cash biopic, Walk the Line. This time, he was applying to his own songs the "tone" of Cash's earliest Sun singles. On those, the resonance of Cash's baritone and the clipped, percussive sound of the guitars and upright bass made drums superfluous. As such, Burnett is returning to the approach of what many believe is his greatest solo album, 1980's Truth Decay.

"I did that record without drums," he remembers. "We sat around in a circle and just played. Working with those guys-Jerry Douglas, Edgar Meyer, Mark O'Connor and Roy Huskey-led me into the world of O Brother, Where Art Thou? We recorded that with one mic, so the instrumentalists were several feet away. When you put a mic too close, the attack overwhelms the tone. Singers can get close, and it sounds exciting, but a drum or banjo has too much attack. When the drums are loud, they force everyone else to play loud too. It forces you to play through a microphone into an amplifier and back from a monitor, you're further removed from the source."

Burnett is stretched out in a chair-all six-feet-four-inches of him-in front of his hotel's stucco wall. His silver hair is cut short, and he wears a black suit that makes him look like a 19th-century preacher. There have been times when Burnett has climbed into the pulpit to skewer the contradictions and dysfunctions of contemporary America by casting it as "Zombieland" or "Fear Country." These apocryphal pronouncements were accompanied by stabbing, jagged music.

But on Truth Decay, 1986's T Bone Burnett and this year's The Other Side, Burnett becomes a different kind of preacher, one whose comforting hymns assuage wounds and channel longing. The opening track on the new album is "He Came Down," a lulling, rolling river of song that praises a hero who may or may not be a Messiah. The vocal is backed only by Linden's tumbling dobro figure. "My wife Callie and I were having coffee one morning," Burnett recalls, "and she asked me something about Appalachian music. I played those opening lines-'After he climbed the mountain high, he came down'-as a kind of explanation. I liked them. I asked myself, 'Is he coming down from drugs? Is he coming down from heaven or from his high horse?' When I started chasing the song down, I didn't think of it as religious but as mythical, as everything we've learned from Greece and India."

It's just Burnett and Linden on the second song too, but on the third they are joined by Rosanne Cash and bassist Dennis Crouch. On the fourth and fifth songs, Rosanne is replaced on harmonies by the two women in Lucius: Jess Wolfe and Holly Laessig. On the sixth song, mandolinist Stuart Duncan and singer Peter More are added. Thus the album begins at its leanest and quietest and gradually expands without ever losing its hymn-like, country-blues feel-and without using any percussion heavier than a tambourine. "T Bone felt there was a natural arc to the way the songs played," explains Linden, who not only played on every track but also co-produced the album. "It started out with just him and me then adding Dennis and Rosanne. That was his way of reeling you in. Then you get to 'The Town That Time Forgot,' and it sounds like the climax of the Ten Commandments."

During the pandemic, Burnett broke his own longstanding rule against buying guitars that were too expensive to lose. He went ahead and bought three instruments he's always wanted: a 1949 Gibson Southern Jumbo, like the one Don Everly played on "Wake Up, Little Suzie"; a 1959 Epiphone Texan, like the one Paul McCartney played on "Yesterday," and a 1932 Gibson L5, Maybelle Carter's guitar. The new guitars soon sparked new songs. The first was "Come Back." "T Bone sent me an email at the end of '22," Linden explains. "It said, 'I just got three new guitars; why don't you come over and we'll play them.' Then he called me one morning and said, 'I just wrote a song, can I come over and play it for you?' That was 'Come Back,' and we started recording on February 15, 2023. He'd come over every day at noon and we'd work till six. He'd come over and work on songs, just chipped away at them. He's got such a great vision of what something can be, so he's extremely patient."

"Ringo asked me to write a song for him," Burnett says. "I'd always liked his voice and his way of telling stories, so I decided to write him a Gene Autry song on the L-5. That was 'Come Back.' Once that happened, it all started happening. On the first verse of that song, it sounds as if those four lines rhyme, but actually they're alternating rhymes though they're very close. That made me want to write in perfect rhyme again. When you start writing in perfect rhyme, it sounds like a classic song. I find it's freeing, because when you find a rhyme, you can work backwards from that, and you can go in either direction. I never would have said something like 'I feel you gone' without looking for a perfect rhyme. It's a phrase that feels completely new."

Linden and Burnett first met on a 1991 Bruce Cockburn tour. Burnett had just produced Cockburn's Nothing but a Burning Light album, and Cockburn had just hired his fellow Toronto guitarist for the road band to support the record. Burnett played parts of the tour, and he bonded with Linden over their shared love of the blues. In 1997, Linden moved from Toronto to Nashville, where Burnett often worked as a producer. Burnett's wife Callie Khouri was a showrunner for the TV series Nashville from 2012 through 2016, and the couple moved permanently from California to Tennessee in 2020. "He and I loved so much of the same music," remembers Linden, who also worked on the TV series, "especially early blues, I'm so connected to '20s and '30s blues and also Howlin' Wolf. From the first time I met him, I was blown away by T Bone's sense of calling as a musician. He felt that playing music was a beautiful thing, and he was so eloquent and heartfelt in how he talked about it. He's a towering figure, both literally and figuratively."

The blues element flavors all the songs on The Other Side, sometimes subtly, sometimes obviously. It's most apparent on "Sometimes I Wonder," co-written by Burnett and Linden. The song is anchored by a relaxed, two-bar Jimmy Reed-like riff, reinforced by off-beat handclaps as Burnett and harmony vocalist Weyes Blood sing, "He heard her singing in a mournful tone." "That definitely comes out of Jimmy Reed," Burnett agrees. "When I was growing up in Texas, Jimmy Reed was like the Beatles. Everyone's repertoire was part Jimmy, part Chuck Berry, part Buddy Holly. All three of them were great songwriters; all wrote their own music when not many people did. His touch and his tone were incredible-and yet easy to play, like the Carter Family. In my day, the first songs every guitar player would learn first would be 'Wildwood Flower' and 'Big Boss Man.' I wanted a woman to sing on that song, but it needed to be a deeper voice. So I asked Natalie Mering, who goes by Weyes Blood. I'm a big fan of Flannery O'Connor, and I was interested that a young woman would adopt one of O'Connor's titles as a stage name."

Burnett grew up in Fort Worth, where at 16 he played on the garage-rock classic, "Paralyzed" by the Legendary Stardust Cowboy. Through his hometown pal Stephen Bruton, who played guitar for Kris Kristofferson, Burnett met Kristofferson, Bob Neuwirth, Steven Soles and Willie Nelson. When these men made a 1974 trip to Hawaii, Burnett, Neuwirth and Soles co-wrote "Hawaiian Blue Song." It remained unreleased until Burnett added a much needed bridge and harmonies from Soles and the song became part of the The Other Side album.

When Bob Dylan decided to do the Rolling Thunder Revue in 1975, he asked his former road manager, Neuwirth, to put a back band together. That's how the virtually unknown Burnett, Soles and David Mansfield wound up on the legendary tour of small New England venues. Afterward, that trio made three albums as the Alpha Band between 1976 and 1978. "We met on the Rolling Thunder Tour," Burnett explains, "and we've remained good friends through the years. We were scuffling around on the street when Bob swept us up and put us on stage and gave us the benefit of his energy and his audience. In many ways, it's been downhill ever since. Steven's an amazing musical intellect. I haven't co-written many songs over the years, and most of them have been with Steven and/or Bobby Neuwirth."

It wasn't until 1980 that T Bone Burnett released his first solo album, Truth Decay. But thanks to his mid-1980s work with Los Lobos, Elvis Costello, Marshall Crenshaw and the BoDeans, Burnett became more acclaimed as a producer than as an artist, and he directed his energies in that direction. When he did record under his own name, it was usually with an edgy kind of satirical surrealism-reinforced by the music as much as the lyrics. "Almost all my work since the time I was a teenager has been about this dystopia we're currently in," Burnett says. "As a kid I learned about Ivan Pavlov and his experiments with dogs. It was clear to me that the experiments he ran on animals were now being performed on humans. I had this recurring dream that there was a line of people wrapped around the block, waiting to have their right hands removed and replaced with consoles."

"Then in 2005, I walked into an L.A. coffee shop, and everyone was staring at their phones," Burnett furthers. "I realized they didn't have to cut off our hands, they just convinced us to keep the consoles in our hands at all times. When I was living within and writing about this dystopia, a lot of my work was hard; the tone was hard. Only by learning how to accept the dystopia in my own life has my tone become kinder, a better tone for my work, for my relationship and for my friends. This album reflects that."

|

|