|

Taken from Hour.ca (March 16, 2006)

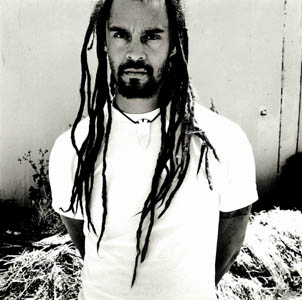

Natty dread

The iconic Michael Franti challenges the hip-hop nation

by Bugs Burnett

Franti knows key to staying human

photo: Anton Corbijn,

courtesy Michael Franti |

Michael Franti and I are blabbing about dreadlocks when I mention that legendary Black Uhuru frontman Michael Rose has dreads that now measure over six feet long. "I've been growing them since 1976," Rose told me some years ago.

"The last time I cut my hair was in 1989," says Franti.

Back in those days, Franti, the adopted son of white parents in Oakland, California, had formed the Beatnigs with turntablist Rono Tse. Then Franti released an album as half of the Public Enemy-influenced Disposable Heroes Of Hiphoprisy, challenging materialism and misogyny in rap music, which was then followed by his current band Spearhead, whose 1994 debut Home addressed such issues as homelessness and AIDS. Today, Spearhead's brand of soul and R'n'B branches out to dub, and Franti himself has become a Gil Scott-Heron of sorts, a voice and conscience of a maturing hip-hop nation.

Following the 2005 release of Love Kamikaze: The Lost Sex Singles and Collectors' Remixes, a Spearhead collection of previously unreleased tracks plus remixes of songs from his 2001 Stay Human album, last November Franti found himself performing an acoustic set before inmates at Folsom County Prison.

"It was a life-altering experience," Franti recalls. "I was really scared shitless going in there because they hadn't had anyone play there since Johnny Cash [37 years ago]. I played for about 55 prisoners and 30 of them were lifers. I asked one of the guys what helps him get up every day and he said, 'The only thing I have left is my ability to give and receive compassion.' I saw the room transform when the music started. It restored my faith in music."

Franti follows the hip-hop scene with avid interest, right down to Jamaican dancehall, which itself gave birth to American hip-hop and reggaeton, Spanish-language dancehall that has taken Latin America by storm. In fact, legislators in the Dominican Republic, upset over the slack lyrics in reggaeton (sound familiar?), attempted to ban the genre of music from that nation's airwaves this past January.

"Any time you have music that connects strongly with youth culture, especially at the street level, it arouses fears in people who are in control," Franti explains. "I see it in my all-black neighbourhood. I see the effect hip-hop has on young people here, and going to community meetings I've heard reactions against hip-hop by the police. When you have youth grow up in that [deprived] environment, what else do you expect them to talk about? Let's try to look at the larger picture. How can we bring support to the community? Do that and you'll see hip-hop change."

Franti is currently touring with his documentary film I Know I'm Not Alone, a musical journey through war and occupation in Iraq, Israel and Palestine. The special screening is followed by a Q&A session and an acoustic set that will feature Franti's great song Stay Human. But in our world, how does Franti himself stay human?

"It's about connecting with other people," Franti says, "the experience of culture through music, laughing, that's how I stay sane. The moments I feel most alive are on stage. It's about feeling connected to people. I think that's one of the great opportunities God has given us - learning to get along."

Michael Franti

Performs at Théâtre Outremont (1248 Bernard W.), March 17

|