|

Taken from The Sydney Morning Herald (Aug 02, 2021)

The idiosyncrasies, inspirations and horrors of Sinead O'Connor

The Irish singer tells her story of a life full of abuse, genius and struggles.

by Michael Dwyer

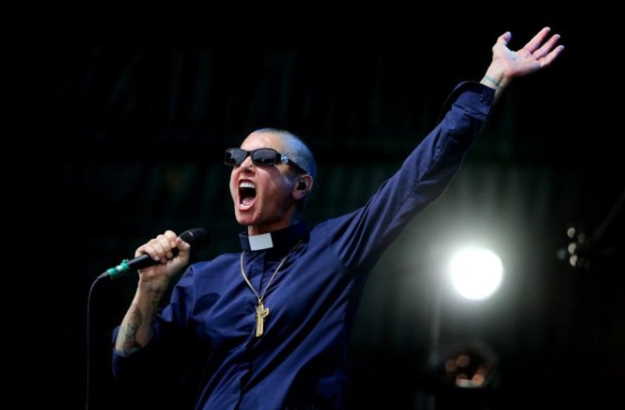

According to Sinead O'Connor, "when one lives with the devil, one finds out there's a God". Credit: Robert Charles |

Sinead or Prince? Sorry, it's time to choose. Her account of the one night she spent at his grim Los Angeles palace is not the kind of story that leaves you on the fence. (She accused him of being a devil worshipper, in case you missed that little revelation.) The delusion spectrum may be wide and slippery at the upper end of the pop business, but one of these two rock stars is completely crazy.

I know, the c-word is on the naughty list in these enlightened times. It's meant in the same spirit in which O'Connor calls herself "as nutty as a f---n' fruitcake and as crazy as a loon". Mental illness is the pointedly exposed nerve binding her fractured, often deeply uncomfortable memoir.

It's her mother's illness that dominates the first of these three parts, written in the voice of the daughter she battered into hospital and police protection. Family "should be a comforting word. But it's not," O'Connor writes near the end of this surreal and harrowing section. "It's a painful, stabbing word. Cuts the heart into pieces."

She follows this, mind you, with a portrait of her father bursting with affection. Her three siblings and four children each earn similarly ecstatic dedications and everything, in the end, is for the now departed mother who made her childhood hell.

Nobody said it wasn't complicated. The contradictions of love and violence are stark and dizzying. In this story, love ultimately wins in a mystical package deal with God and music, but the broken home remains the void beneath our heroine's feet as she takes off, a hopelessly ill-prepared pop sensation, in Part Two.

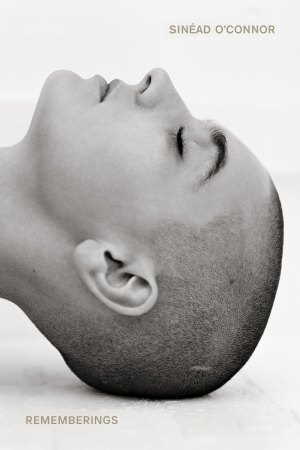

Rememberings, Sinead O'Connor, Penguin, $45 |

In our late-dawning post-Whitney/Britney awareness of how the pop patriarchy works, the highs and vicious lows of Sinead O'Connor's dramatic music career are, sadly, more easily understood. She recounts shaving her head in defiance of her record company's directive to dress more girly. She also declines their advice to abort her first child.

As the Grammys and cash roll in, she alone sees the crash looming: "I'm a punk, not a pop star." Snubbing awards shows, telling the truth about the child abuse and theocracy that poisoned her homeland and her upbringing, she was a pariah long before the infamous Pope-tearing incident on American TV in 1992.

She writes of this absurdly over-publicised moment as a personal watershed: at last, liberation from the tacky treadmill where good girls shut up, act sexy and sell records. The meltdown the rest of us imagined actually came much later: a medical procedure in 2015 led to mental breakdown, suicide attempts and a final, opportunistic humiliation inside an American rehab scam.

She blames this horrific episode for memory loss that, in turn, leaves a 20-year hole in her narrative. But then, The Whole Chronological Story is very much out of fashion in the world of rock memoirs. Unless you're a hardcore fan, the album-by-album exposition that pads out most of Part Three is a bit of a slog.

Infinitely more readable are random episodic flashes of heroes such as Michael Hutchence, Lou Reed and Muhammed Ali; and fleeting sideswipes at Bono, Adele, Peter Gabriel and the guy from the Red Hot Chili Peppers (he says they did so, she says "only in his mind").

To be sure, given all her vividly recounted trauma - not to mention her Herculean marijuana intake - the reliability of our narrator is a reasonable concern. Her rage still burns so brightly at times that it's impossible to tell her literal truth from flailing retribution.

"All rock stars are rule-breaking, delinquent, drug-guzzling pigs, careless sluts, unfit parents and alcoholic maniacs," she writes in a climactic open letter to her father. Joking. Kind of.

Similarly, the less enlightened reader can only wonder about the threads of reason that lead her to various all-consuming spiritual paths, from Jesus to the kabbalah, Rastafarianism and most recently to Islam. "God is a concept," John Lennon once sang, "by which we measure our pain." O'Connor's spin: "When one lives with the devil, one finds out there's a God."

Only the hardest heart could deny her right to that truth. The ghost who speaks through the family piano? Well, OK, she was only five. When it comes to clear-as-day visions of a red-haired angel in a red and white sweatshirt sitting on her sleeping daughter's chest though ... well, you do have to wonder what really happened that night at Prince's house.

|