|

Taken from Hindustan Times (Mar 29, 2020)

The discreet charm of Karsh Kale

The guy behind the famous Train song in Gully Boy is the face of Asian Underground for an entire generation. What makes Karsh Kale the king of Alternative Music?

by Ananya Ghosh, Hindustan Times

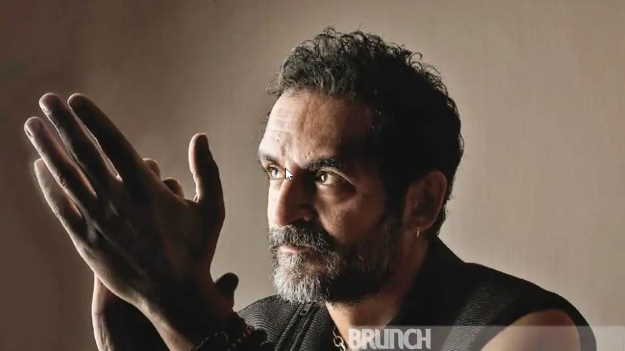

Karsh Kale is one of the pioneering musicians who defined the Asian Underground scene of the early '90s (Aalok Soni) |

To one generation, Karsh Kale needs no introduction- he is one of the pioneers who defined the Asian Underground musical scene of the early '90s. To another generation, he is the guy who scored the famous Train song for Gully Boy (2019). Point this out, and he laughs. Because Kale has always been fiercely protective of his independent artiste tag, and it is ironic that he is known to GenZ for a film song.

"I have experienced situations where I knew it was my skin tone that didn't land me the gig!"

"I am 45 and I have been doing this for too long to be swayed by adulation," he says. "The joy of making music is what you have written and not what happens after the track is released. It is not because you have got so many likes on YouTube, but because you believed in that piece of work before anyone else even heard it. Everything else - numbers and views - is just an illusion."

Brush with Bollywood

Kale admits that if he had such success with a film song early in his career, he might have made more of the praise. Now, however, with a long view of different music scenes, pop, electronica, rap, Bollywood, it does not matter so much.

"I always knew my relationship with Bollywood would be intermittent," he explains. "However, I have always been roped in when a unique approach was required for an interesting story. So I have never been a Bollywood go-to-guy, but an alternative. This is a position I enjoy."

"People assume the bigger audience base you reach, the better. For me, that has never been the case!"

The record producer, songwriter, composer and DJ has collaborated with the likes of the late Pandit Ravi Shankar, the late Pandit Hari Prasad Chaurasia, Ustad Zakir Hussain, Anoushka Shankar, Nora Jones, Sting, Chaka Khan, Herbie Hancock, Amel Larrieux, and Bill Laswell. Recently, he worked with Amaan and Ayaan Ali Bangash to create an album called Infinity.

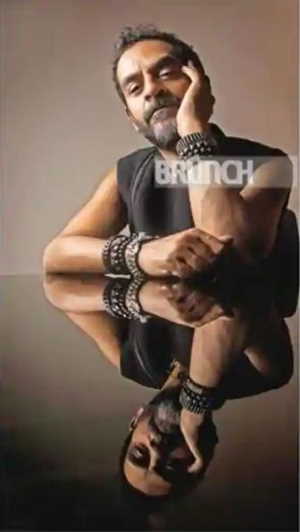

Last year, Karsh Kale had one of the biggest Bollywood hits to his credit(Aalok Soni) |

While explaining how each piece of music has its own journey, Kale reveals that he was working with Ankur Tewari, his frequent collaborator, for another Bollywood film. "We were doing the music for Tumbbad (2018) but those were initial days. It was very experimental, ambient, non-language music with alien-sounding vocals. The movie took a different path and the music was too out there for the project. So we put it out as a single called Little Whale. It was released the same month as Gully Boy.

"I am 45 and I have been doing this for too long to be swayed by adulation"

"It is not always necessary to have a huge release. People always assume that the bigger audience base you reach the better. For me that has never been the case. I have always admired people like Zakir Hussain and Peter Gabriel...people who made artistic choices and kept the integrity of what they do alive, never letting their music get exploited."

Not a one-trick pony

Kale refuses to be pigeon-holed into any particular music scene. "The moment I realise doors are closing, I jump out and do something entirely different. I would hate to be a one-trick pony," says the multi-hyphenate musician, who at this phase of his life, prefers to call himself a composer. "For decades I loved travelling and performing live more than anything else. Nowadays, I seek situations that require me to stay in one place for a while. I like being a composer. I often play the piano for fun because I have a lot of music stirring inside me. I still enjoy performing, but I'm finding a new balance with it now. I think music producer is the best way to describe all that I do."

He became a household name in India with MTV India's music incubation project, Coke Studio. "I did one season on Coke Studio. I had a very mass audience, but that audience knew only just that side of me. That was a particular sound more geared towards the Indian audience," he recalls.

Far from the maddening crowd

Kale seems a tad disappointed with the live music scene today. "For me, playing live is always about capturing the moment," he says. "There is that dichotomy of a well-rehearsed show, with one piece where I flip it on the artistes I play with. That is what makes every live show a unique experience. Otherwise it is a recital."

"I would hate to be a one-trick pony"

He describes the performances of today as video games because there is so much light and electronica. "I don't understand why 10,000 people want to stand and stare at a DJ waving his arms around and swaying to music that keeps the same tempo for two hours. There is nothing spontaneous in the shows. People are happy with the same thing that they listen to on YouTube."

The breakout musician

Kale was the first Indo-American musician to have signed a solo recording contract in the United States. He dropped a self-produced EP in 2000 and followed it up with his debut solo album, Realize (2001). He also joined Tabla Beat Science, a musical group whose members included Bill Laswell, tabla player Zakir Hussain, percussionist Trilok Gurtu, sarangi maestro Ustad Sultan Khan and electronica artist Talvin Singh, among others.

He agrees that today the international scene is looking better than ever for Indian artists. "America is currently having a Brown revolution of sorts. Indians are thriving in film and TV as well as comedy, music, politics. You would be hard pressed today to find a show or movie without an Indian character. This is very different from our generation's experience," he says, recollecting his teenage years. "I was isolated. We were living in Long Island which had very few Indians. So Indian music was my way of holding on to something that felt very distant in terms of culture and my own identity. I grew up listening to Stevie Wonder and a lot of early hip-hop. At home, my dad played a lot of Hindi film music and Indian classical music by Hariprasad Chaurasia, Pandit Ravi Shankar, Pandit Shivkumar Sharma, and of course a lot of Zakir Hussain."

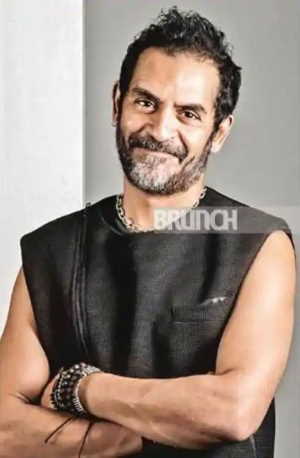

Kale was the first Indo-American musician to have signed a solo recording contract in the United States (Aalok Soni) |

In fact Zakir Hussain did a lot of fusion in those days. "Him, Trilok Gurtu, Bill Laswell are the people I listened to in the '80s. It was not electronic music, but a different kind of fusion. They were already opening the doors for us."

"I always knew my relationship with Bollywood would be intermittent"

However, Kale has Bollywood to thank for his music career. Well, in a way! The film music from the '60s and '70s influenced how he approaches his own musical stories, he says, but it was a trip to Bombay in 1978, when he was four years old, that decided the course of his musical journey. "We spent a couple of days with one of my father's best friends. He was a composer in the film industry, and had a living room full of instruments. I, however, was drawn instinctively to the tabla."

When West met East

Kale's tabla-playing Indianness was confined to his Long island house. Outside, he was a rock drummer! "I never really tried to merge the two until I was in college. But then I started producing electronic music, trying to incorporate tabla. I realised soon that I was not the only one doing this. There was a movement brewing simultaneously in London and India and all over the world. It was about making sense of the confused identity of the diaspora. It was the '90s! There was no social media, but we were on the streets, pasting posters on top of other people's posters! We were very competitive. We would go door to door," he says.

"When anything goes mainstream, it quickly becomes a cookie cutter version of itself... thus watering down the sentiment that made it rise to the mainstream in the first place"

Before this, the Indian music scene was for Indians only. Now young artists of Indian origin wanted to open it to the world. "We were inviting people to share our culture, telling them who we are," says Kale. "Everything was an experiment. In the '90s, many diasporic Indians changed the mainstream's view of what an Indian or Asian artist looks and sounds like."

It still wasn't easy though. "Being a drummer and tabla player, I was often hired to be a session musician. However, on the live scene I experienced situations where I knew it was not my playing but my skin tone that didn't land me the gig. These experiences however, taught me to find my own niche and create something unique out of my own multicultural make-up," he says.

The rolling stone

Today, almost three decades on, Kale says his approach to music has changed. "The older I get, the less I feel part of any scene. When I was younger, my music was informed by what was happening in the clubs and on the global fusion stage. Today, I listen to my inner muse without much concern for what styles are trending. It's a good thing to finally understand what makes me unique as an artist and a storyteller. Also the older I get, the less I feel the need to wave any flags, culturally or otherwise. I feel like a citizen of the world, and more a part of a continuum rather than a generation."

But he is buoyant about India's simmering underground hip-hop scene finally bursting into the mainstream. "Hip-hop is perhaps the biggest and most widely adopted genre around the world. I hope we see Indian MCs and producers working with hip-hop artists from all over the world," he says. He also points out that it can go either way from here. "When anything goes mainstream, it quickly becomes a cookie cutter version of itself, imitated by those who know little about its history, thus watering down the sentiment that made it rise to the mainstream in the first place. It's up to those representing the genre to keep it evolving."

Kale is also evolving. "I don't want the same things I did when I was 18, and I don't want to die doing the same thing. I have written a few scripts and I want to direct a film. But at the right time!"

|