| |

Taken from Reggae Vibes (February, 2004)

The Father's Place

A Concert Review Essay

by Gregory Stephens

ZIGGY MARLEY & MICHAEL FRANTI / SPEARHEADSUNSET STATION, SAN ANTONIO, FEB. 10, 2004

When Michael Franti and Spearhead were booked as an opening act for Ziggy Marley's first tour as a solo act, I immediately arranged an interview with Franti, and booked a flight to Texas for the concert in San Antonio.

I have followed both artists from the beginning. I reviewed Ziggy and the Melody Makers on their "Conscious Party" tour of 1988, and have seen the band several times in California and Texas. I was disappointed in much of Ziggy's music during the late 1990s. But Ziggy's first two CDs of the 21st century, "Spirit of Music" and "Dragonfly," revealed an artistic rebirth. Ziggy had finally escaped his father's shadow and developed his own voice, it seemed to me. And he did so by recording music that often no longer really fit within the reggae genre. Ziggy's decision to rent his own house in L.A. while recording "Dragonfly" was a courageous move, necessary to escape an often inbred scene in Kingston, or Miami, the two primary homes of the Marley clan, where there is no escaping the expectations of being Bob Marley's oldest son.

|

Franti's career I followed at close range while living in the San Francisco Bay Area during the 1990s, from the early Beatnigs project, through the phenomenal 1994 CD "Disposable Heroes of Hiphoprisy," and several albums with his band Spearhead. I'm a father of biracial children and a scholar of interracial relations, so Franti's background resonated with me. He was a biracial child "who was adopted by parents who loved me/they were the same color as the kids who called me nigger/on the walk home from school," he said in "Socio-genetic Experiment."

Franti's latest CDs, "Stay Human" (2001) and "Everyone Deserves Music" (2003), were a cut above anything else being done in American music, in my view. They showed remarkable growth as an artist and human being, although this wasn't always what hip-hop fans wanted to hear. Great production, addictive hooks, fierce social criticism, and uplifiting love-and-unity anthems all combined to make "Stay Human" an instant classic. "Everyone Deserves Music" was more subtle, but over time revealed itself as the mature work of an artist at the height of his creative powers. Franti's "Bomb the World" has become an anthem for those who maintain both hope and a critical consciousness in the cynical post-9/11 world.

"Six foot six above sea level," in the signature line from "Listener Supported," Franti, a former basketball player at the university of San Francisco, is singular presence. When he walked barefoot towards me for our interview, his dreads up in a tam, I saw him as if in split screen. He has a regal bearing, but also a huggable brotherliness, a ragamuffin, latter-day beatnik vibe. I told Franti about a mutual friend in his hometown of Davis, California, and then he stepped gingerly across the parking lot on this cool drizzly evening.

On the tour bus, Franti sat beneath an illuminated Che Guevara poster. I compared that iconic shot of Che, the implacable "true revolutionary," with the peaceful self-assurance that Franti exuded. Franti's music is still radical, but a compassionate generosity of spirit permeates "Everyone Deserves Music." This stood in marked contrast to a bitter mood that was often dominant in works like "Chocolate Supa Highway," or the radio skits on "Stay Human" about a racist governor (voiced by Woody Harrelson) executing a Mumia-like prisoner on election eve.

Franti's practice of yoga over the last two years has probably played an important role in his shift in tone. But I also think that his focus changed in the post 9/11 world. The stakes were lifted. It was no longer enough to voice rage against the bad guys, to name enemies.

"Even our worst enemies deserve music" sings Franti.

Franti has evolved beyond mere opposition, to sing redemption songs:

"We can bomb the world to pieces - But we can't bomb it into peace."

That awareness of the need to create a new world, not just oppose the old, has colored Franti's songwriting in creative ways. The world's hatred will make you think about the conflict of your personal life in new ways, and vice versa:

"Hatred is what got me here today. But I know that love is

gonna set me free"

Franti hugged us after our interview, like he hugs many people who cross his path. Watching his band at soundcheck, I was excited about seeing them interact with a new audience, most of them come to see Bob's son, Ziggy. This was the fifth date of a joint tour that started in Arizona, on the eve of Bob's 59th birthday, and would end in Eureka, California on March 31.

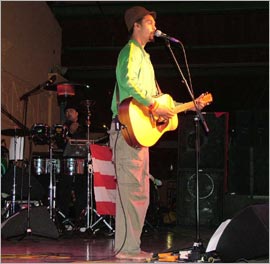

Photo courtesy of DJ-RJ |

Photo courtesy of DJ-RJ |

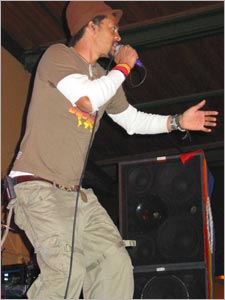

Michael Franti and Ziggy Marley presented a striking contrast, in their stage personae. Franti is a showman who has a great time on stage. He has a charismatic ability to fire up an audience and keep them involved. He feeds off his long-term band-members, especially bassist Carl Young, who had just released his own jazz-fusion /R&B style CD, as well as guitarist Dave Shul and percussionist Roberto Quintana.

Franti told me that his primary musical inspiration continues to be the classics of reggae and soul, mostly 1970s. This comes across in his talent for hooks, and a performance style that may be closer to Sly Stone than any other template. Live, it became clear how Franti's musical imagination centers on interaction with his audience. The show was filled with high-energy call-and-response enactments of hooks like "all the freaky people make the beauty of the world."

Or this simple, hummable, and blessedly inclusive affirmation of equal rights from the anti-war song "Crazy, Crazy, Crazy":

"No life's worth more than any other - No sister worth less than any brother"

Spearhead didn't play much reggae. "Bomb the World" live was a far cry from the remix hip-hop/dance hall version he cut with Sly and Robbie. "Pray for Grace" did have a reggae influence. The only other straight-up reggae song, "Listener Supported," has some lines that call to mind the UK reggae smash "Pirates" (by Cocoa Tea, Shabba Ranks, and Home T.):

"High crime treason we broadcasting sedition

Commandeering airwaves from unknown positions

Live and direct we coming never pre-recorded

With information that will never be reported

Disregard the mainstream media distorted

We're coming listener supported."

That's the essence of Franti and Spearhead. Rebel music from and for the people. It's no wonder he's a repeat guest on shows like "Democracy Now!". On "Rock the Nation" he sang:

"Everybody wants to be some fat tycoon

Nobody wants to sing a little bit out of tune

Or be the backbone of a rebel platoon

It's too soon to step out of line

You might get laughed at, you might get fined"

These lines connect on several levels. They can be read as a critique of the materialism in which most hip-hop wallows. And they are certainly prophetic of the "watch what you say" timidity and conservatism that has descended on American popular culture post-9/11.

But not Franti. On "We Don't Mind" he sings, with a swing you've got to hear to believe:

"I'm prepared now to suffer the penalties for speaking the truth."

Photo courtesy of DJ-RJ |

Photo courtesy of DJ-RJ |

Franti often calls his group a "rock band," although clearly funk and soul are cornerstones of their vocabulary. The notion of being a rock band is more a matter of on-stage attitude, I think: Franti's roots in punk as well as hip-hop are still evident. But the reggae influences come through in many ways, from Franti's dreads, to lyrical inflections, to the unity themes that one can hardly hear in any other genre of music nowadays. This reggae audience clearly had no trouble at all connecting with Franti. When he made an exaggerated nod at "The Sound of Music" on "Stay Human," people clearly got the

joke.

When I asked Franti what he thought it meant to be a real revolutionary nowadays, his answer reflected how his thinking has evolved. "Sometimes our evolution is moving too slow, and people jump off to give the circle a push," he said. But even more, "a revolutionary act right now" is just to spend some time reflecting on "how we want to be viewed as a nation.". I thought about that when, on tour in a genre (reggae) that is intensely homophobic, and in the midst of a divisive debate about gay marriages, Franti had Ziggy Marley fans singing along to these lines:

"It ain't about who you love. It's all about do you love"

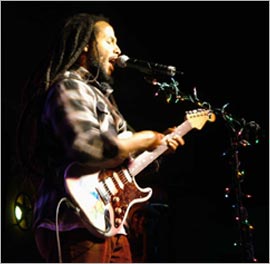

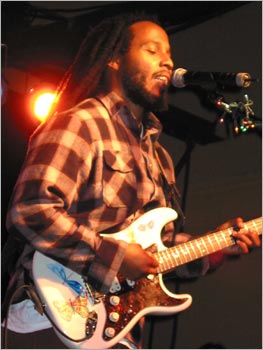

Ziggy Marley's band carried a very different vibe. Although Ziggy is recording a lot of music that is not reggae, for this tour he had assembled a world-class band that played arena-calibre reggae rock. I was simply awed by the sophistication of the sound and the clarity of the mix. I haven't heard a lot of live reggae since my children came along, but this was a quality of live reggae I'm not sure I've heard since Bunny Wailer's band at Sunsplash in 1988. And it was all anchored by legendary drummer Carlton "Santa" Davis. The greatest pleasure of Ziggy's set, for me, was simply listening to this master at work.

It was also a gas to watch and listen to the interplay between two outstanding guitarists, Ian "Beezy" Coleman and Tekashi Akimoto. The rolling mountain of bass came from Paul Setnnett. The rest of the band consisted of Michael Hyde, keys; Angel Roche, percussion, and the lovely Tracy Hazzard, backing vocals.

The band started slowly with "Melancholy Mood." This was followed by Ziggy's "peace in the Middle East" song, "Shalom Salaam." It took a Bob cover, "Wake Up and Live," to get his audience in gear. This was the first of four or five Bob covers, too many I think. But it's understandable for an outdoors concert in February when a lot of your audience comes expecting you to "channel" your father.

Photo: Gregory Stephens |

Ziggy appears a bit heavy-set now, with thick legs that sometimes seemed planted on the stage. "Channeling" may be a good word for what it looks like he's doing. He only rarely looked out at or spoke to the audience. Sometimes he would go into trance with a very private muse. There was a long section in the middle of a cover of Bob's "Africa Unite" in which Ziggy repeated, over and over, until it became painfully awkward:

"Your grace, you are the foundation."

Ziggy could have been in communion with either of two father figures, either his dad Bob or Bob's "perfect father," Haile Selassie. But it was not a contagious sort of trance. I found myself increasingly focused on his terrific band, and just listening to some of Ziggy's lyrics, which are often visionary. "I Get Out" is a catchy song about escaping the boxes people put you in-something with obvious relevance for Ziggy. "In the Name of God" is a powerful condemnation of those who kill in the name of their deity. It has a line stated almost casually that lingers long afterwards:

"All religion should be wiped out"

Photo: Gregory Stephens |

Ziggy also performed several songs that show his talent for writing a pop hook inflected with his father's natural mystic:

"Rainbow in the Sky," "Good Old Days," "True to Myself."

Ziggy remains an enigma as a performer. If I think about him as an artist, and put aside expectations that he will entertain me, then I remember that there have been musicians that resolutely refused to play the role of entertainer. Miles Davis famously turned his back on his audience. Ziggy has a much sweeter vibe than that, of course. But whereas Franti's performance brought his songs to life in new ways, Ziggy's performance almost detracts from his songs. They are private meditations, and I suspect that they are not really conceived with the audience foremost in mind, as with Franti. But sometimes their beauty takes my breath away. In particular, there is a passage from "Don't You Kill Love" which has become a quiet anthem for me:

"It's the greatest things in life

That call for the most sacrifice

Are we brave enough?"

A lot of fans across the United States who have written reviews of this pairing on Franti's <A href="http://www.spearheadvibrations.com/" target=_blank i <>Spearheadvibrations.com website came to see Ziggy, but left as Franti fans. Many of them felt Ziggy should have been the opening act. From a performance standpoint, I would have to agree. But this has been a good pairing for both artists, I think.

JULIAN MARLEY & THE MAU MAU CHAPLAINS

FLAMINGO CANTINA, AUSTIN, FEB. 11, 2004

left to right,

David Roach (keys),

Steve Carter (guitar),

Moe Montsarrat (bass),

Mike Pankratz (drums)

Photo courtesy of DJ-RJ. |

Steve Carter on left...

Moe Monsarrat on right

Randy Kirchhof on left- background

Louis Meyers on right-background

Photo courtesy of Mike and Betsy Pankratz. |

I saw another interesting contrast between opening band and headliner the following night in Austin. The gig was in the close quarters of the Flamingo Cantina, where I had the honor of helping my Idren DJ-RJ put together a set of rare Marley dubs and remixes. Again it was the "present absence" of the father, Bob, which drew in the massive through his son, Julian Marley. But it was a relatively unknown act, the Austin-based Mau Mau Chaplains, who played the most entertaining music.

The Mau Maus (named after a dominant 1960s Kingston street gang) are a middle-aged collective, an all-star group comprised of former members of some of the best of 1980s Austin reggae groups. I knew some of these guys from back when I was a songwriter on the 1980s Austin scene.

I hadn't seen keyboardist David Roach since I used to buy gear from him at Strait Music in the 1980s. I remembered that David had retired from the music biz at a rather young age, in spite of being in demand, because he was a father and was not willing to tour. As if reading my mind, David greeted me and made a joke about how this band would not cross the river for gigs. "The Red River?" I asked. "No, the Colorado River," he responded (which divides North from South Austin). The Mau Mau Chaplains are the ultimate local band, family men most of them, making world-class reggae, but as fathers and breadwinners, mostly sticking close to home.

Like several other members of the band, Roach wore a cowboy hat, boots, and a beard. He was definitely a South Austin sort of guy, which is to say, the old Austin, not the high-tech north side. They were kind of relics from the Armadillo World Headquarters era, when a bunch of guys dressed up in cowboy garb, calling themselves I-Tex and the Frontier Dub Boys, and skilfully blending classic reggae with real country-western, somehow seemed almost natural. Still, the shtick carried enough cognitive dissonance to make for compelling entertainment. They were "widely believed to be the only band in the world that combined songs from Johnny Cash and quotes from Chairman Mao into a danceable reggae medley," as keyboardist Randy Kirchof writes in a hilarious band history.

It would be hard for many to imagine just how "authentic" much of the reggae played in Austin over the last three decades has sounded. It's a sound that is certainly not Jamaican, but not derivative, either, like so much U.S. reggae. We're talking a rich legacy of central Texas reggae groups including the Lotions, I-Tex, The Killer Bees, Pressure, and into the present, Root 1 and Tribal Nation. One thing is easy to explain: the Mau Mau Chaplains bring together over 150 man-years of stage experience. This goes back to Hawaii in 1973, when Roach and his friend Alan "Moe" Monsarrat, a bassist, brought home Marley's Burning and began figuring out how to play those backward beats. The band's history includes sojourns for some of the band members in New Orleans. And when they get on stage together, all these influences come together seamlessly: island music, second-line, old-school country, and more.

They opened with a terrific version of the UK group Black State's "Legalize Collie Herb." Their setlist certainly showed which part of the reggae tradition they feel comfortable in: Toots' "Reggae Got Soul," the Heptones' "Fatty Fatty," and Black Uhuru "Shine Eye Gal."

I was enjoying their version of the Meditations classic "Woman is Like a Shadow" when the multi-talented bassist Courtney Audain told me, "my wife doesn't like that song. She says it's sexist." I checked the lyrics:

"Never let a woman know how much you care

Because they will do things to hurt you"

Courtney's wife is right, but it's a point of view that rings true to the experience of many guys. There are a lot of troubling attitudes about gender in Jamaican music. You can hardly play your favorites without forwarding some of those prejudices. But Courtney, a Trinidadian who has toured internationally, was being forced to think about that culture in a new way, because he is now sticking close to home, helping raise his children.

The Mau Mau Chaplains also played the Joe Higgs song "Family":

"I got family all around the world"

Maybe that's a telling lyric for guys that don't get around much anymore!

If you said Mau Mau was "just a local cover band," you would be mostly right. But that would be about like saying that Jamaican music mostly recycles old riddims over and over. That's also true, but the trick is in how this tradition is reinvented. Louis Meyer's burning slide guitar, along with the soulful five-part harmonies, make their interpretations something special. (Those harmonies are also voiced by drummer Mike Pankratz and guitarists Boomer Norman and Steve Carter).

As is their custom, the Mau Mau Chaplains closed with an a cappella rendering of "Rastaman Chant." All those country inflections sounded beautiful, and moving, and were a reminder, to me, of just how closely related roots reggae and roots country are in spirit.

Photo courtesy of DJ-RJ |

Photo courtesy of DJ-RJ |

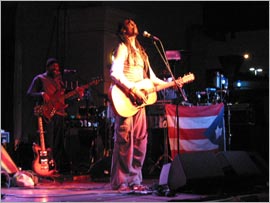

By contrast, Julian Marley's band sounded very green to my ears. I doubt that mattered much to the youths crowding the stage. But my dominant impression was that this was a college-circuit level reggae band. They have a niche to fill, and because of the name, they will always have an audience. But their style of reggae rarely rose above the generic.

There was a young dread on stage whose sole duty was to wave a red-gold-and green Lion of Judah flag. From where I stood, the flag floated back and forth across the images of a Bob Marley concert video (at the Rainbow in London) that Flamingo Cantina projects non-stop on one wall. It was visual confirmation of just where Julian stands. I doubt any of these bands-Franti, Ziggy, the Mau Mau Chaplains, or Julian-would have been performing these concerts without Bob having set the example. But in Julian's case, the repeated references to his father, both direct and indirect, were a pointed reminder of how much he is indebted to these family ties.

Julian's first album A Lion in the Morning was widely panned. One critic called

Julian "the ugly duckling of Bob's offspring," but offered that his sophomore release A Time and Place (on the Bob-founded Tuff Gong label), was a relatively pleasant surprise, showing that Julian had matured into "at least an attractive parrot," if not a beautiful swan. That may be damning with faint praise, but "tell the children the truth," as Bob sang. There is no getting away with comparisons with the father at this stage.

The song that struck me as catchiest, in Julian's live set, was "Harder Dayz." And that was based on Bob's "Natty Dread" riddim. On the album, "Harder Dayz" includes a hip-hop breakbeat. In fact, there is a musical stew on A Time and Place that didn't come through with the fairly generic reggae performed by Julian's live band.

Two other songs from Julian's set that stood out for me depended, on reflection, completely on associations with Bob. The lead song of A Time and Place has this hook: "Come with me to my father's place." Any casual reggae fan will have heard similar themes from many Rastas. The only reason this has any particular resonance, in Julian's version, it seems to me, is that it's double meaning: Julian's talking not only about Zion, the father's place for all Rastas, but also about Bob's place on Hope Road, a new Zion gathering the

children.

Perhaps Julian's most original lyric, for me, was:

"Sitting in the darkWaiting for your fatherto put you in the light"

Who else could write that but a youth whose vision emerged in the absence of the father? Again, there is a double meaning: Julian is praying to the father, but he's also waiting for Bob the father to lead Julian from loneliness into the limelight. That is a terribly poignant lyric, like Kymani Marley's "Dear Dad" on the Crazy Baldhead riddim.

The Father's Place

Thoughts about our mothers and fathers

These concerts got me to thinking about the role of the father, in the lives of all of we who are playing and promoting bass culture. This is personal for me: I've got custody of two children, and being a full-time single father means that live music has almost disappeared from my life. It means I had to pay for help with my kids to be able to make this trip. So I am hungry to see artists, and freedom fighters, who talk about how parenting changes their life and art.

Of the four lead singers I saw Feb. 10-11, three grew up either not knowing their father (Franti), seeing him only intermittently (Ziggy), or almost never (Julian). And the absence of their fathers has been a powerful presence in their artistic imagination. Franti talked about this in an interview with Amy Goodman on Democracy Now!--that absence played a big part in making him want to raise his voice for the underdog, for other people that also feel pain, often in large part because the absence of their own fathers.

But that pattern gets repeated. Ziggy Marley, a father of several children, is travelling so much that when asked what his home base is, he just says "Earth."

We often think about singers in bass culture as freedom fighters. The rhetoric of equal rights and justice is central to that culture. The singers ritually call on that legacy. But how many freedom fighters stick around to raise their own children? No, they take their cause on the road. It's still almost always the women who stay home to raise the next generation. And when that generation comes of age, what will they think the father's place should be? Not at home, surely?

I have never heard any of the Marley clan sing about being a father (or mother) themelves, although they have all sung about the father repeatedly, in an abstract, spiritual sense. Bob did sing about his children once, in "Keep on Moving." Aside from that, my sense is that in this tradition, the father's place is revoluting (or siring more offspring) away from home. The father is a distant horizon towards which we move. And the home front is still ruled by women. Even though we often refer to their domain as "the father's place."

Photo: Gregory Stephens |

Franti sang about his son in "Water Pistol Man," a touching and profound lyric:

"Water pistol man

Full of ammunition

Shooting out fires on a world-wide mission

But did you ever think to stop and shoot some water

On the flowers in your own back yard"

When our mission takes us far from yard, we have to water thirsty flowers wherever we find them. Franti does a lot of this gardening work in prisons, which are full of men who hated or did not know their fathers, and who are not around to raise their own children. Ziggy does his part through projects like Unlimited Resources Giving Enlightenment (URGE), which as he describes it, is a corporation he started to send money to needy youths he sees while driving by.

"Anywhere the Father send us, we will go, because it's the Father's work," Yami Bolo once told me. "The Father will always keep attacking Babylon, you know?" he said.

I understand that sense of mission very well. It's something I feel sent to do, in ways small and large, in each and every day. But like some of those dads in Austin, I've been sent to the father's place in my own life. If I can't attack Babylon, or sing the praises of the Creator and her Creation, with my children present, I won't be doing it at all. So there is something in Jah music that still leaves me hungry. I want to honor the "Queenly Character" of this world, too. Singing praises to the King alone sometimes feels like "just another

illusion."

At the same time, I honor the sacrifices that all the fathers have made, and that the mothers of their children make, so that they can barnstorm the world, lifting our spirits. And oh how much we need that communion! But I wonder when the Father will send us home. When Zion will be not just a holy mountain in a foreign land, but a place where fathers and mothers join forces to nurture the next generation.

|

|