| |

Taken from Hyperallergic (Jan 26, 2019)

British Rock Meets Modernism

Clive Arrowsmith's photographs of Peter Gabriel spotlight a short-lived era when rock aspired to the condition of art.

by Tim Keane

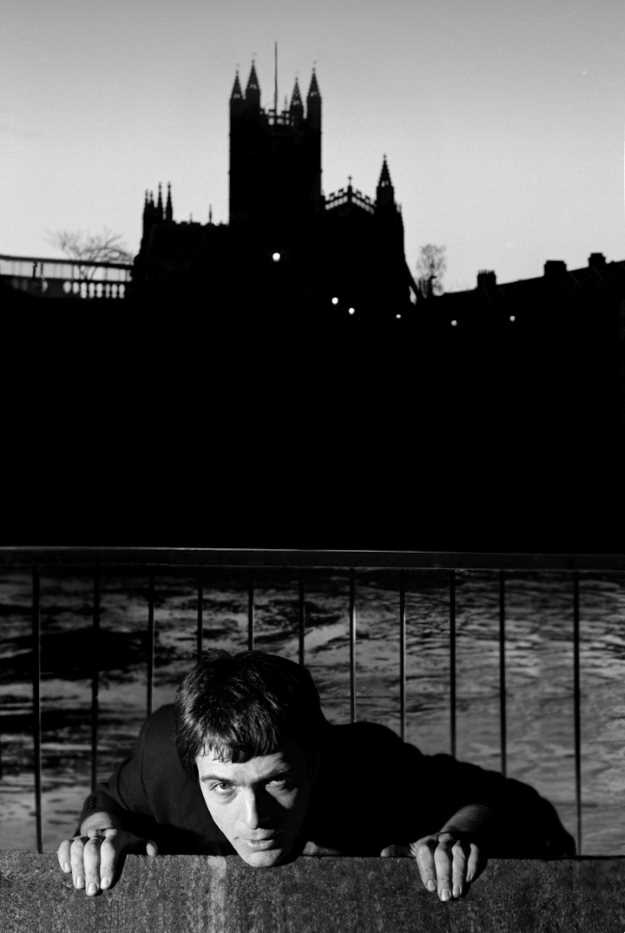

Clive Arrowsmith, "Peter Gabriel" (1978) (© Clive Arrowsmith, image courtesy The Museum of Bath Architecture) |

BATH, England - Part messiah figure, part marketing gimmick, the rockstar trope would seem to be both exhausted and exhausting. So why is it enjoying so many revivals, from Oscar-season buzz around Bryan Singer's Queen biopic Bohemian Rhapsody (2018), to the globetrotting blockbuster exhibition David Bowie Is (2013-2018) celebrating The Thin White Duke's multimedia career - film and stage actor, painter, dancer, songwriter, producer, and fashion designer?

Peter Gabriel: Reflections at The Museum of Bath Architecture adds a small-scale, locally focused note to the frontman nostalgia-fest, gathering together 29 portraits of the British musician taken by photographer Clive Arrowsmith in the 1970s. Like the Queen and Bowie revisits, Reflections spotlights a short-lived era when rock aspired to the condition of art, and few rock musicians were more ardent in this aspiration than Gabriel.

Born in 1950 and educated at Charterhouse School in Surrey, Gabriel formed Genesis in the late 1960s with classmates Tony Banks and Mike Rutherford. They didn't care about rock-as-macho-performance. Instead they focused on the collaborative art of songwriting and set out on a path cleared by formally innovative rock albums like The Beach Boys' Pet Sounds (1966), The Beatles' Sergeant Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band (1967), and The Who's Tommy (1969). But the band also had their ears glued to American roots music, to Motown, and to British folk

Gabriel's career, like those of Bowie and Queen's Freddy Mercury, proves that rock, that mass consumer product, was able, for a time, to break ground and even function like an outpost for late Modernism. In other words, rock could experiment with its relatively new form, replace its already formulaic song structures with complicated poetics, reconfigure its stage presentations, and in the process, expand the range of what popular music could express and mean.

Genesis performing live at the Auditorium Theatre, Chicago, on November 20, 1974 (photo by Tony Morelli via Wikicommons) |

For certain young rockers, this involved major risk. It meant refusing marketplace demands and ignoring audience expectations. It meant hitting the road and piling on huge debt. Accessibility was an anathema. When the hit-making UK music show Top of the Pops offered Genesis a coveted TV slot in 1974, they turned it down. In concert, Gabriel adopted a similarly contrarian approach. Instead of repackaging the frontman's preening, strutting bravado, he disappeared behind masks, make-up, UV and black lighting, and abstract and surreal costumes.

Satirized by hilarious mockumentaries like This is Spinal Tap (1984) and Life of Rock with Brian Pern (2014-2017), Gabriel's visual theatrics remained tongue-in-cheek, punctuated by droll wit and lewd humor, even as their seriousness of intent took on a cinematic dimension.

Unexpected shifts of tone became a virtual necessity to their live act. Genesis's "Supper's Ready" (1972) is a 23-minute song that starts as an acoustic ballad about a couple's estrangement, builds into a cycle of visions inspired by Ovid's poetry, British folklore, and Christian allegory, and ultimately reunites its contemporary lovers amid an apocalypse, with lyrical snippets lifted from The Book of Revelations.

Then there was the music's technical complexity. Borrowing from classical, folk, and jazz, riffing across unpredictable chord progressions and time signatures, Genesis electrified European audiences. In a bid to widen their American audience, the band staged a tour in support of The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway (1974), a double album with lyrics written entirely by Gabriel, which The New Yorker recently revisited and compared to James Joyce's Ulysses (1922). Demoralized by the pressures of being the public face of the band, Gabriel quit the scene when that tour wrapped in 1975.

Clive Arrowsmith, "Peter Gabriel" (1978) (© Clive Arrowsmith, image courtesy The Museum of Bath Architecture) |

Viewed through Arrowsmith's lens, Gabriel's departure turns out to have been well-timed, at least from an artistic standpoint. By 1975, art rock, or as it is known today, progressive ("prog") rock, was old-school avant-garde. The Moody Blues, Yes, and Emerson, Lake & Palmer were on the way out. The Clash, Blondie, and Joy Division were on the way in. Gabriel spent that fluid, post-punk era strategizing a new musical direction. And that transition is where Clive Arrowsmith's Reflections find Gabriel.

The visual style of Reflections harks back to Arrowsmith's origins as a photojournalist. In 1966, after graduating from Kingston College of Art, he was commissioned to photograph the painter LS Lowry in a village outside of Manchester. Rather than separate the aging artist from that provincial setting, Arrowsmith's series, catalogued in Lowry: At Home Salford 1966, Unseen Photographs, immerses the painter in his native milieu - pictured in his messy home studio, on random street corners amid strangers, and reflected in local shop windows.

After the Lowry project, Arrowsmith was in demand, working in the booming fashion and music industries on both sides of the Atlantic, rubbing elbows with Irving Penn, The Beatles, and Stanley Kubrick. He first photographed Gabriel during his Genesis years for British Vogue; those outtakes are included in Reflections. Those images are both macabre and funny. In one, the singer appears as just a head, his body and limbs swallowed within a bright white pyramidal form.

In contrast to the Genesis-era Vogue images, the musician looks thoroughly at home cavorting in Bath in 1978. Though the singer has cut his hair and traded in showbiz threads for a bank manager's suit, the images maintain a disorienting effect, borrowing from the grit of American film noir and the cool of French New Wave.

Clive Arrowsmith, "Peter Gabriel" (1978) (© Clive Arrowsmith, image courtesy The Museum of Bath Architecture) |

Still, the portraits exude an eccentric, self-conscious Englishness. Gabriel is captured jogging on country trails, wielding camera lights, or leaping into the air. Arrowsmith exploits the tension between the urban and the rural. His suit and tie, along with the camera gear and electric lights, clash with the foothills and grassy footpaths of England's West Country. The singer looks younger and more innocent than he was, with his mop-top blowing in the wind, or his clean-shaven face breaking into a childlike grin. Or he seems like a sleepwalker in a concrete dreamscape, poised to trip, or tip over, or fly off into the air.

As a local boy made good, Gabriel parlayed that clout to gain access to the city's famed Roman baths, where Arrowsmith could shoot in the early morning before the tourists arrived. Arrowsmith infuses these compositions with references to Rene Magritte's Surrealist images of businessmen cut into silhouettes of water or sky. Almost submerged in the ancient baths, dressed in a waterlogged suit, the musician closes his eyes as he spoons invisible soup from a saucer, while the shrouding steam seems to transport him into the afterlife.

Water frequently adds an extra touch of drama, even in portraits that might otherwise look like outtakes from an unearthed 1970s detective film. In one, with Bath Abbey and the River Avon in the background, he appears to be sinking into the river's currents as he grabs a rail along the city's promenade.

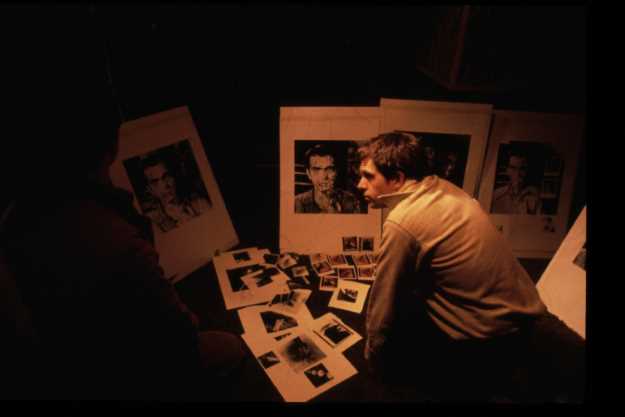

Peter Gabriel selecting cover art for the album "Peter Gabriel 3" (May 1980) (photo by Larry Fast, © Peter Gabriel Ltd) |

Reflections occupies a gray area between fine art and a record label's publicity shoot. In Gabriel's return to music, he embraced both of portraiture's functions. Like Arrowsmith's portraits, the singer's album covers feature images in which his features are distorted or semi-obscured. Such oblique portraiture parallels his songwriting, in which he adopts the perspective of the outcast in songs about faith healers and indigenous exiles, cross-dressing cat burglars and anxiety-ridden assassins. His third solo album combined electronica, industrial soundscapes, and African inspired percussion. When executives at Atlantic Records in the US previewed it in 1980, they deemed it "commercial suicide," rejected it, and dropped Gabriel from their label.

Perhaps ironically, Reflections will likely draw many visitors thanks to the singer's commercial breakthrough LP, So (1986), which made him rich and famous on the strength of an Otis Redding homage, "Sledgehammer," and its groundbreaking music video created by a team that included the late animator Stephen R. Johnson and the Quay Brothers. In turn, the elliptical, semi-surreal portraiture in Reflections might inspire museum-goers to discover the comparably darker pockets in Gabriel's back catalogue, including tracks on So, such as "Mercy Street," which channels the waking dreamscapes of American poet Anne Sexton; "Milgrams 37," about 1960s psychological experiments in human obedience; and "Don't Give Up," about the suicidal toll of unemployment in postindustrial Britain.

![Catalan artist Evru (formerly Zush) in 1992 with his painting commissioned by Gabriel for 'Digging in the Dirt' from Us (1992); describing his concept, he has stated: '[T]he world under the earth is all dirty [...] I imagined that there is the real world, the world where we live and there is this subterranean world, this world under (us) [...] our mind underworld.' (photo by Stephen Lovell-Davies, © Peter Gabriel Ltd)](../Archives/ArtView_Pics/PeterGabriel_Reflections_Clive-Arrowsmth@Hyperallergic_20190126_06.jpg)

Catalan artist Evru (formerly Zush) in 1992 with his painting commissioned by Gabriel for "Digging in the Dirt" from Us (1992); describing his concept, he has stated: "[T]he world under the earth is all dirty [...] I imagined that there is the real world, the world where we live and there is this subterranean world, this world under (us) [...] our mind underworld." (photo by Stephen Lovell-Davies, © Peter Gabriel Ltd) |

Abandoning the pop limelight, Gabriel returned to his roots and attempted crossover links between visual art and music. His critically acclaimed Passion (1989), originally composed as the soundtrack to Martin Scorsese's film The Last Temptation of Christ, (1988), features cover art from a self-portrait by British painter Julian Grater, whose work takes on a second life on as a portrait of the all-too-human Christ dramatized in Nikos Kazantzakis' novel, the book that inspired Scorsese's film adaptation. A few years later, for the artwork that accompanies Gabriel's introspective Us LP (1992), the singer commissioned original works by such international contemporary artists as Rebecca Horn, Yayoi Kusama, Mickael Bethe-Selassie, Andy Goldsworthy, and Finbar Kelly, who responded to individual songs in the creation of their work.

Furthering this interplay of music, visual experience, and local culture, Reflections' curator Tim Beale has taken his own contemporary photographs of sights in and around Bath that crop up in Gabriel's music, and incorporated them into the exhibition. One of Beale's photos, a stunning nighttime view from a summit outside Bath, depicts the scene that inspired Gabriel's anthem, "Solsbury Hill" (1977), a folk-rock ballad about rejecting the security of the sure thing for a future of untold risks.

Tim Beale, "The Lights of the City" (2018) (© Tim Beale, image courtesy The Museum of Bath Architecture) |

Today, rock fans and critics draw no distinction between rock as pop and rock as art, and so it's easy to lose sight of the ambition to create hybrid forms, original sounds, and a broader emotive range that stirred the postwar genesis of rock music and fueled it for decades. If you don't believe me, re-watch Queen's performance at Live Aid, now nearing 160,000,000 views.

If a short song or whole album can be as formally and emotionally complicated as, say, the range of experiences that make up our bizarre, fucked-up human condition, then, it turns out, certain frontmen of a certain bygone era in British culture might be worth revisiting from time to time. They remind us that - maybe - this very late Modern medium of rock music still has a lot of juice left in it after all.

Peter Gabriel: Reflections, curated by Tim Beale, continues at The Museum of Bath Architecture (The Countess of Huntingdon's Chapel, The Paragon, Bath) through February 3.

|

|