|

Taken from Salon (Nov 29, 2018)

Funk was the black answer to "Star Wars": Take the trip with "Tales From the Tour Bus"

Salon talks to producer and historian Nelson George about the rock radio "apartheid" and why funk never got its due

by Melanie McFarland

Mike Judge Presents: Tales from the Tour Bus. (Cinemax) |

Regardless of the musician featured, each episode of "Mike Judge Presents: Tales From the Tour Bus" begins with the same disclaimer: "The following is about real people and real events. However, due to the passage of time, and, in some cases, indulgence in both controlled and illicit substances, details of some tales are a bit hazy."

Par for the course for any pop music history exploration. But in his underappreciated animated gem, these words should make you rub your hands together in hungry expectation.

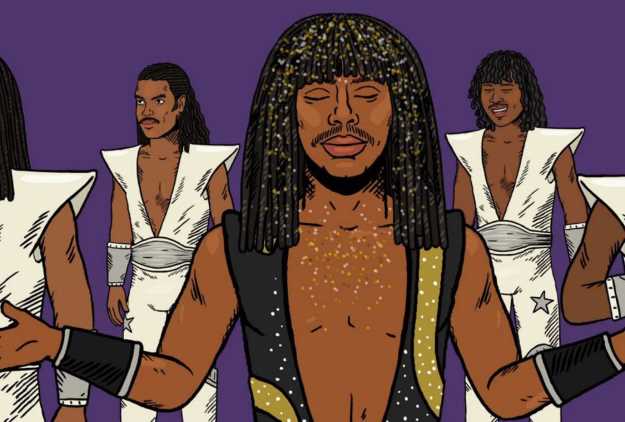

The second season of the Cinemax series kicked off at the beginning of November relatively quietly with regard to the amount of coverage it's received in the press. But these new episodes, airing Fridays at 10 p.m., are anything but soft. Season 2 of "Tales From the Tour Bus" is a psychedelic journey into the relatively unsung world of funk, a genre born out of the soul era and raised, by the likes of George Clinton and Bootsy Collins, bumping to bass grooves and flying a Holy Mothership while whacked out on LSD.

The new season opened with a Technicolor half-hour devoted to Clinton before moving on through nasty funkmaster Rick James who merited two episodes. His name pulled my attention, an increasingly difficult feat in a time of too much television, and not for the reason most may suspect.

The late Rick James is known to many as the subject of one of the most legendary "Chappelle Show" skits and his sad catchphrase "cocaine is a helluva drug." Long before that, though, he was a fixture within black music, boasting an extensive body of work that extends much further back than Dave Chappelle or MC Hammer, who sampled James' signature lick from "Super Freak" for his monster hit "U Can't Touch This."

But to anyone who knows anything about James' wild and alarming life, the opportunity to see its highlights animated by Judge, the man who brought us "King of the Hill" and "Beavis and Butt-Head" before going high-falutin' by creating the multiple Emmy-winning "Silicon Valley," is too good to pass up.

And the two-parter on Rick James does not disappoint. Neither does the season's second two-parter on James Brown, which airs its first episode this week. Future episodes this season profile Morris Day and The Time and the indomitable and relatively little-known Betty Davis. In fact, this is a show that's worth discovering via SVOD, if only to enjoy binging multiple trippy episodes in one sitting. Stumbling upon new chapters as they air, however, is its own treat, in that there simply aren't any delightfully cultish series like this one out there right now.

"Tales From the Tour Bus" visually fascinates and educates by animating footage of interviews with the actual musicians, family members, historians and the people who knew them best. But its deeper appeal lies in cartoonish illustrations of those tales and testimonials from the people who knew and worked with the featured legends, leaving in every verbal idiosyncrasy and thoughtful pause the way that the person speaks it. Many of these unfettered, insane yarns can only be done justice via animation, but even their tragic or frightening recollections are granted a measure of benediction via Judge's artistic rendering.

And as much as there is to love about the first season of "Tales" and its devotion country music artists, season 2 reaches the next level by diving into the largely unsung stories of funk stars, who formed a bridge between '60s soul and most of the popular music we prize today, particularly hip-hop.

"Hip hop has been about the street and about very grounded stuff," explains Nelson George, the filmmaker, author and music historian serving as a consulting producer on season 2. But even now, he says, funk's influence is reaching through the years to influence the music of today. "There is a sense of trying to not just do the street thing, but trying to find a way to elevate it. And I think that funk is the most elevated black music, the most theatrical black music style that we've had."

Prior to this week's airing of the series's two-part episode featuring James Brown, the first of which debuts Friday at 10 p.m., Salon chatted with George about his involvement with the series and why funk musicians in general haven't gotten their due in the same way that giants of other pop music genres have.

Please note that this interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Let's talk about how you came to be involved with the second season of "Tales From the Tour Bus." Your hand in it is very apparent.

I more or less got involved in helping them navigate the world of funk because of my background. I was at Billboard magazine in the '80s, and I'd covered these guys for years.

I also did a documentary that was on VH1 called "Finding the Funk." So I was really able to work as a bridge between the production and getting George and Bootsy, some of the other characters. I helped them out with the Betty Davis episode. Alan Leeds, who's in James Brown's episodes a lot, is a good friend of mine. Or Jimmy Jam Harris, who's in the Morris Day episode. So I worked as a sort of a bridge between the world of Mike Judge and the world of funk.

The first thing the "Tales from the Tour Bus" narrator [voiced by Judge] points out at the beginning of the season is that these are all music legends, but you don't really see many, if any, documentaries about them. There have been references, of course, like in "The Defiant Ones," as I recall, it was pointed out that a lot of samples came from that genre. And obviously these are great stories. So why do you think it is that we've seen, say, films on James Brown but next to nothing on Rick James, Bootsy Collins, George Clinton, even Betty Davis?

Funk is the stepchild of music history.

Soul music was incredibly celebrated while it was happening. Aretha Franklin, the Motown artists, the Al Greens, they all have been considered great parts of American culture and so forth. And then hip hop has made its own lane, and that has become such a big thing. But funk is the bridge between those two things. Funk is an evolution of soul music. Funk is the music of bands.

As the Bootsy episode illustrates, a lot of them had been background guys, session guys. Funk allowed them to step forward and be the stars themselves. That was a problem, marketing-wise, and I think racially, quite honestly. It's easy to see James Brown, Aretha Franklin, even The Temptations, which is only five guys, and identify with them. It's easy to see a rapper with one mic. Or Run DMC, which was two guys and DJ.

A funk band was like nine guys, eleven guys, or eleven guys and girls depending on the band. People really were taken aback by that. There were big, big hit records that came out of funk - Earth, Wind & Fire had a bunch, P-Funk, Ohio Players - but they were hard to identify because there were so many people in the band. Also funk was, you know, ten, eleven people wearing space outfits. The look, literally the visual of funk, put people off. You knew the band, but you didn't know the players in many cases.

And then, funk kind of evolved in this funny moment when you went from top 40 radio where you played everything: Motown played right next to the Stones, played right next to the Beach Boys, played right next to Tom Jones. Funk came up in that era of the late '60s and early '70s - the '70s in particular was its heyday - when there was just real de facto line. Funk was the music that should have been playing next to Led Zeppelin on rock radio.

Interesting. Why?

If you listen to the Isley Brothers, P-Funk, Earth, Wind & Fire, Kool & the Gang, these bands, they're not that different from what Chicago or Led Zeppelin or any number of bands on the white side of rock were playing.

But there was an apartheid that went on in rock radio. With the exception of Jimi Hendrix and maybe Sly, they didn't play any black bands. And so that became a real barrier to funk's evolution. It never quite got the audience that it deserved because it was sort of stuck just in a black music mode. And I think both soul music and hip hop were both able to be accepted as pop music. Funk music never really got that acceptance.

So to me, with this season of "Tales," getting this opportunity to give these guys a platform has been incredible. I mean, Betty Davis is one of the most interesting stories in popular music, and she's the only really known to, really, the true funk connoisseurs.

Betty's a woman who became a muse, you know. She changes Miles Davis' wardrobe. She changes Miles Davis's approach to sound. She introduces Miles Davis to Hendrix and, through that, changes the direction of jazz for a decade or so because the electronic direction Miles went in affected all the young musicians. At the same time, she leaves Miles and she becomes her own artist. She becomes her own star. And she makes these really incredibly hardcore, highly sexual records that scare people, essentially.

She she's a remarkable story, and having her as part of the season is one of the things I'm really proudest of. Because I feel like, of all of the people in our season, she is the least well known in some ways is the most impactful, both for her impact on Miles and her own breakthrough work as a solo artist.

In the context of Mike's animation, taking on music legends makes sense. And I get why the first season would take on country music, since it would appeal to the audience that would be most likely to subscribe to Cinemax - i.e., affluent white audiences. Season 2 is really interesting for the reasons that you state, but also, funk is a genre that really lends itself to animation. I was actually telling a friend of mine recently that one of my very first memories of being exposed to music was a Bootsy Collins song. And, of course, Bootsy was on "Yo Gabba Gabba."

That's right.

This is a musical genre that lends itself well to animation and nostalgia the same time. It also is very educational for the same reasons, in that not all of these are artists that most white audiences would be familiar with. They would not necessarily connect to, say, Bootsy or Rick James in a deep way, aside from the more recent pop culture references.

I mean, people know Rick James more for the Dave Chappelle stuff than they do for the actual music. Which is a shame. You know, when you go back and listen to the music, Rick was a very, very gifted songwriter and arranger and singer. It brought me back to the albums and how well made they are. Also, one of the things about funk that it becomes very clear when you watch the series is that funk was, in some respects, black hippie music .

That is to say, James Brown started funk and Brown is the innovator. And he didn't give a damn about anything but the hardest hardcore stuff. But Rick and Bootsy and George, and to some degree Morris [Day] through Prince, and definitely Betty Davis, they're taking elements of rock culture, in terms of some of the showmanship, in terms of some of the staging and some of the outrageous subject matter, and they're bringing a black aesthetic on top of that, along with some interesting space stuff or futuristic stuff.

Funk is very interested in non-Christian religion; there's a lot of references to pyramids, Egyptology, eastern mysticism, all these things play a role in all of this music. And then when hip hop came in, hip hop was kind of essentialist.

It's not as a spiritually based, either. Maybe it was easier to understand? Whereas with funk, you had to join them, you had to take a trip with them that was both sonic and somewhat conceptual.

I've become a real champion of funk music because the more I look at it, the more I see how it was, in a way, the black answer to "Star Wars" and all these movies from the '70s. "Star Wars" and "Close Encounters," and this idea of going into space - all of those movies were criticized because there were no black people in them except for maybe one guy. Whereas funk was situating these musicians in a spacey, sort-of-elevated environment. The Mothership landing is basically the black version of "Star Wars."

Yeah. That was an amazing feature in the George Clinton episode.

Funk was a very visionary form that allowed the kind of black expression that you might see in painting or you might see in even the avant garde jazz thing, or you might see in literature in the work of Ishmael Reed, or Octavia Butler. There were all these different corollaries, all these things were going on around the same time.

If you go back and read the cultural writings of the era, you would read, "Disco is this, disco is that." Funk was never as fashionable. There was no Studio 54 of funk. It wasn't a music that a particular elite group liked, ergo, it didn't get the media coverage. Whereas disco is this thing that was in New York and very glamorous, funk was perceived to be sort of a gritty, kind of dark, black thing. And it didn't cross over the same way disco did.

I'm going to go back to something that you had said just about the whole idea of this crossover with science fiction. This year we've witnessed the increased visibility of black producers and black directors in Hollywood. We've witnessed the success of "Black Panther" and Ava DuVernay's profile rising as the director of "A Wrinkle in Time." Discussions about Afrofuturism have gone more mainstream. And I wonder whether any of this impacted the direction and the development of the second season of "Tales From the Tour Bus."

Well, the development of this season was already in progress, you know. But when you pick Bootsy, George Clinton, Rick James and Betty Davis as part of your season, you're going to deal with ideas and looks, particularly, that are futuristic. Everything about it was forward-thinking and not just situated on this planet. I think that was just more a matter of this coinciding, somehow, in this moment.

But maybe there is something going on in the culture. Among the other things I think that I think it played some role in putting funk back on everyone's radar screens are two albums we should mentioned. One is the Childish Gambino record, which is very much situated in the '70s version of funk, and then to some degree Bruno Mars' last album, "24 K Magic," which is more situated in kind of an '80s version of funk. And he did "Uptown Funk" before that.

So there is something going with funk in the culture that's been going on for a year or two that plays into what you're saying. Somehow the fact that "Black Panther" comes out the same year as "Tales from the Tour Bus," which comes out in the wake of Childish Gambino and some of the other things that have happened, all seem to be part of it this moment where people are looking for something a little different.

Most of the season that's aired far has shown the bridge connecting George Clinton, through Bootsy, to James Brown, the subject of this week's episode. And of course, the Rick James episode included Prince. So one might surmise there would be a Prince episode, but instead, "Tales" is going to feature Morris Day and the Time - which I totally agree with, by the way. But I'm sure there will be people wondering why this season doesn't feature Prince.

Well, Prince is a little different. Morris was Prince's funk alter-ego. I mean, in other words, Prince was consciously aware of trying to divide his musical mind into different sections. You know, when he had albums with the Revolution, they tended to be pop rock with some funk on it. When he did Vanity 6, that was more, like, girl group meets nasty funk beats. But when he wanted a band, he created The Time as his funk alter-ego. It was really was more going for a black radio or black audience thing.

So for our show, it made more sense to look at Morris and The Time who, who really took funk into the '80s using different instrumentation and a different aesthetic, but still very much about the showmanship and about the band music of funk. And Morris himself had an interesting life and had his own conflicts about becoming this character.

And then you had Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis [who went on to produce superstar acts such as Janet Jackson]. You had amazing musicians who came out of that band, who also sort of extended to the electronic era. So it made more sense to do it that way than trying to squeeze Prince into a half-hour format.

But what's interesting about the show is so many people show up inside different episodes. You're going to see Joe Tex in the James Brown episodes, and a few other people who you may not expect, in very funny ways. I mean, just having Prince walk around in the Rick James episode was hilarious. And we get Prince not from the point of view of this great genius, but the point of view of Rick James' band and how they perceived him. I thought that was great because it gives you a different look at who he was at that point in his evolution and how he's perceived by his peers at the time.

What's that saying? Something along the lines of, "Great minds innovate and geniuses steal."

Yeah. And that was Rick's beef with Prince. Among people who know the history of the music, that's a very legendary rivalry that's probably not known in the pop world. But people who were into black music know about Prince opening for Rick and that they had this big beef.

At the time when Prince opened for him, Rick was a headlining artist and Prince was a young guy starting out. You can definitely can see how he saw Rick's show and said, 'I can take this, I can take that element, and integrate it into my show' - something that Rick didn't appreciate.

As you said, there are a number of legendary artists popping up in episodes of "Tales." Maceo Parker appears in James Brown, and you mentioned Miles Davis' story in connection to the Betty Davis chapter, which I'm really looking forward to.

You're going to have some real interesting people pop up in that one.

I'm wondering if you've heard any inklings of what musical genre a potential third season would cover. Jazz, maybe?

It's funny. I can't speak for Mike, so I don't want to say. I've pitched a couple of things to him. But in the realm of what's been established, you know, it's got to be a form of music that has some mythology to it, and a form of music that has some outrageous to it. I'm hopeful that that will happen and, and that I'll be involved in it because this was incredible amount of fun.

Having just done a doc on funk where we were basically had stuff from talking heads and we had found footage, to be able to just animate a great story and not worry about finding footage to cover it is amazing. It's so liberating.

I do love the fact that it actually leaves room for creative license at the beginning with the disclaimer. And there's something that you said there that I think really captures the magic of this series, which is that it does make the most of the outrageousness of these figures.

To that extent, a lot of people right now, when confronted with figures like Rick James - who went to prison for his part in a terrible crime - have had to reassess their relationship to their fandom. But what this series does really well is to show what happened, to take those dark times into account as part of the story, while also explaining why a person maintains affection for this music. We see what went into it. And I'm curious to get your take on what animation does in terms of feeding viewpoint.

I just think that you're able to go into these moments and bring people into them differently. It's interesting - with animation, it's obviously a fictional thing in that you're creating images that don't exist for something that you say did exist. But there is something very tangible for us about the animation that makes, even if we know they're cartoons, that makes it feel realer. And that's what really one of the strange things about it.

I have several personal Rick James stories. He was a cartoon character. But he also was clearly a troubled guy in that his success had not liberated him. It had sort of trapped him into a kind of mode of behavior that I think he had a hard time escaping.

And I feel like in some ways, we're able to make that point very well with the animation. The theatricality that Rick had or Bootsy had or George has, had another side, a dark side, in that you become trapped in your own creation. And you can begin to feel that you can get away with anything, or that the stakes are not as high as you think they are. In other words, you feel a certain sense of entitlement and also a certain sense of invulnerability. That eventually affected all of them in some way. They all had to go through a personal trial before coming out the other side.

Rick never came out the other side, unfortunately. But George and Bootsy did. His story actually is quite epic. I'm assuming that someday, someone's going to do a real Rick James documentary or a movie, a longer piece. But I feel like our show gives you a pretty panoramic view of his life.

The same is true for James Brown. My take on him and on Rick James is that both men made great music, but as a woman, I knew would never want to spend any personal time with either of them. But the series does a tremendous job of showing where that drive comes from in a way that I haven't experienced before.

I feel like our James Brown episodes, I would put them up against a movie that been made about him anytime. I think we did a better job, quite honestly, of really getting into his career.

In what respect?

There's a vividness to our type of storytelling. You know, Alex Gibney did a doc on James [ 2014's "Mr. Dynamite: The Rise of James Brown"] and there's obviously that movie. We're definitely better than the movie. I have no question in my mind that were better than the movie. I mean, I worked on this, so forgive me if I'm being too proud, but I feel like we were able to give some nuance to Brown that may not have been captured as well in the doc.

Live action documentaries have a sort of reverence to them, regardless of subject, where some of these small nuances of character and personality quirks kind of escape them. Which is what "Tales" capitalizes upon.

I mean, in a way it's a show about eccentricity. Every person we've done here is very eccentric and non-traditional. None of these people would fit in any nine-to-five job. They had to create their own world order to exist, and I think that the show captures that really well.

Obviously there's going to be a very interesting Rick James thing done someday by somebody. Hopefully. It would be a really good documentary. George, quite honestly, who's retiring next year, deserves a really epic doc. He's had an epic life. All these folks are our major artists who also are incredibly complicated and interesting people. And I'm really impressed with how well we've been able to have the outrageous stuff that happens on the tour but, but also to really situate it in character in a really great way.

|