| |

Taken from Rolling Stone (Oct 31, 2017)

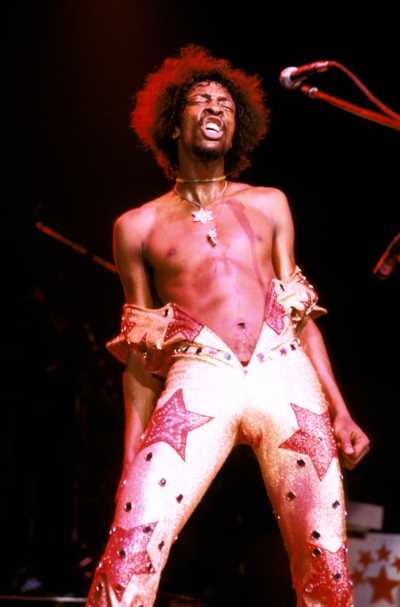

Bootsy Collins on What James Brown Taught Him, Why He Quit Drugs

As the bass icon releases new LP 'World Wide Funk,' he reflects on the perils of stardom, the genius of his late friend Bernie Worrell and more

by Kory Grow

As Bootsy Collins releases his new album, 'World Wide Funk,' the bass superstar opens up about James Brown, Bernie Worrell and why he quit drugs. Credit: Michael Weintrob |

There's a reason why the self-proclaimed "world's only rhinestone rock-star doll," bassist Bootsy Collins, has taken six years to put out his new album, World Wide Funk: He was awaiting the urge. "It's a feeling like you gotta release yourself," the typically hilarious yet surprisingly soft-spoken artist says. "It's like going to the bathroom, man. You know, 'I gotta poop. I can't hold it no more.' I can't hold it, man." Collins laughs at his own analogy and says, "I probably gotta get out more often. I've been pent up too long."

Collins' scatological joke, of course, undersells World Wide Funk. The albumis a continuation of the genre-spanning R&B-funk–hip-hop amalgam of his last release, 2011's The Funk Capital of the World, except with more focus on musicianship. In addition to a typically star-studded list of collaborators, including Snoop Dogg, Chuck D, Victor Wooten, Buckethead and Collins' late P-Funk associate Bernie Worrell, among others, he collaborated with emerging artists in an effort to find a new sound.

"I didn't want to make a record like I've been making before," he says during a lengthy, career-spanning interview with Rolling Stone. "Everybody knows what to expect from me, so I didn't want to do that. I wanted to add a fresh, young energy to it, so I involved some young musicians and had them around me in recording sessions. I know what old funkateers wanna hear, but how do you get out of that if you don't want to just do that?"

Collins says the experience of working with younger musicians like bassist Manou Gallo and guitarist Justin Johnson, helped him accept change, embrace new technology and "open the mind." "They were wild and crazy about the opportunity to be with me," he says, "and they're feeling like they ain't nobody yet, and I'm saying, 'You are.'"

It led him to create the album's bluesy, country-flavored "Boomerang," the upbeat jazzy dance number "Snow Bunny" and the rap-inflected modern funk of album closer "Illusions." To him, it's just a new extension of what the man known as Bootzilla has always been about. "I don't want to leave all the funkateers hanging, so I'm gonna take 'em with me and I'm just gonna build on what we do," the singer says, with optimism beaming out of him. "And then we'll all be out on the high sea, waving and funking and having a good time."

When you felt you were ready, was it easy to get started on World Wide Funk?

Yeah. When I started the record, it just felt right. I didn't know what I was doing as far as what it was going to wind up being. But to me, the hardest thing to do in life is to get started. I grew up with brothers all on the street corner about what they was gonna do. And I was one of them. It just so happened that I learned early that I gotta turn this talk into doing something. My brother had a guitar and he wouldn't let me play it, so I knew I had to get a paper route and started saving my pennies; I started making $2.50 a week and I thought I was rich, man. The guitar I bought cost $29.95. You know how many months that took me to pay for that?

About a year.

Yeah.

There's a track on the record, "Bass-Rigged System," where you play with four other bassists – Victor Wooten, Stanley Clarke, Alissia Benveniste and Manou Gallo. How do you pull something like that off?

It's a thrill. My first concern was getting it down. I knew that if we started vibing, it was gonna go down and it did. At the end of the day it was, "Let's see how we can place these things to make some kind of sense?" There are gonna be people looking, listening to this and wanting to hear what so-and-so played, so I tried to do that part of it so people would actually hear what each one was doing.

I love the album's "Salute to Bernie," which features your recordings with Bernie Worrell before his death last year. What are your fondest memories of him?

Probably a better question would be what were not my fondest times [laughs]. It was like he was the other half of you; he makes you a whole person. He made my music whole. He makes me feel like the part I don't have – the technical part, as far as knowing what chords go together and how to read music – he knows how to make what I play sound like I did on purpose.

He complements you.

Yeah, and he does it without questions. He never asked, "Why did you do that? That ain't the right chord." It would be like, "OK, if that's what you wanna play, let me see what I can do to help it sound right." He was always like that. He was just a joy to be around. We gained so much from each other.

What did he learn from you?

He learned that you don't have to be correct traditionally. Sometimes you can play whatever you're feeling and just make it work. I didn't know any better coming from James Brown's school; James just did what he felt.

What are the biggest lessons you learned from James Brown?

The most important one was that he told me I was too busy; I was playing a lot of stuff. He loved all the different stuff I was playing, but if I were to give him the one – the one beat on every four count – and then play all that other stuff, he said, "Then, you my boy."

He treated me like a son. And being out of a fatherless home, I needed that father figure and he really played up to it. I mean, good Lord. Every night after we played a show, he called us back to give us a lecture about how horrible we sounded. [Affects James Brown voice] "Nah, not on it, son. I didn't hear the one. You didn't give me the one." He would tell me this at every show. One night, we knew we wasn't sounding really good – we were off – and he calls us back there and said, "Uh huh, now that's what I'm talkin' about. Y'all was on it tonight. Y'all hit the one." My brother [guitarist Phelps "Catfish" Collins] and I looked at each other like, "This mother has got to be crazy." We knew in our heart and soul that we wasn't all that on that show. So then I started figuring out his game, man. By telling me that I wasn't on it, he made me practice harder. So I just absorbed what he said and used it in a positive way.

Since we're talking about how you developed your style, I'm curious what you think of this. In George Clinton's book, he said that Parliament-Funkadelic found its stride when you played wah-wah style bass through a Mu-Tron on Chocolate City's "Right On." Do you agree with that?

I think he's right, 'cause after we did that I felt like I had something to offer instead of just being a bass player. I felt like I had a signature. When we recorded that, it set a sound for us as a group – as a band and I guess as a player as well.

"'Flash Light' was more of a Parliament song, and George called it out: 'You know, well, give that to me,'" Collins says. "So he took that and I took 'Bootzilla.' And they both were hits." Credit: Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images |

What was your process like back then? I believe "Flash Light" was a track you recorded with your brother.

Me and my brother used to just put tracks together, 'cause George would always be the one to pick what songs were going for Parliament and what's going for Funkadelic. I had a handle on the songs I liked for myself personally, like for Bootsy's Rubber Band. But [Parliament-Funkadelic's brass section] the Horny Horns and my brother and I would just record tracks.

So when we did "Flash Light," I was in need of one other song on the Bootsy? Player of the Year album. So I recorded "Flash Light" and I recorded "Bootzilla." I happened to like "Bootzilla" for Bootsy's Rubber Band, because that was more the monster I was trying to create. "Flash Light" was more of a Parliament song, and George called it out: "You know, well, give that to me." So he took that and I took "Bootzilla." And they both were hits.

You were talking earlier about the new approach you took on World Wide Funk. Will you be doing much of the older stuff on tour?

I know I might have to do a few, but I'm gonna try to make sure they don't push me to do a whole set like I have been doing. I think this album is going to allow me to break out of having to do that. Because this ain't back in the day. This is a new day and the sooner we embrace that, the better. Being creative calls for change. If I did the older stuff, it would have to be moving forward. Just me being in the mix is old school enough. You're gonna get what I got in me. So I'm looking forward to the challenge.

About 20 years ago, you told Rolling Stone, "I got so tired of living up to that Bootsy character. I'd become a so-called 'star' and I just didn't know how to handle it." How did you find the place where you're at right now?

A lot had it do with time and a lot had to do with backing off "Bootsy" and becoming William again. I came home to see mama one day with all the boys and girls with me, and I had the star glasses on – I was decked out with my leathers on like I was still onstage. I came home, and she slapped the glasses of me. I'm like, "What was that about?" She said, "Go out there and take that garbage out, boy." And I was like, "Oh, man." I was very embarrassed in front of all my friends. But I needed that. That slap right there let me know that when you come home, you take the glasses off. You ain't nobody but William here. And I had to realize that.

A lot of things had to happen to me. I fell off my motorcycle and had a terrible accident. The doctors told me I wasn't gonna be able to use my right arm and I'd never play again. And that scared me to death. So that combination right there was enough to turn me around to say, "Wait a minute. It's all right to be that guy when it's time to be that guy, but you don't have to be that guy at home." I thought I had to be him 27 hours a day.

That sounds like a hard lesson.

It's like the Frankenstein monster: Once you get him up and rolling, that mother gonna turn on you. I had to accept that this was my fault. I'm the one that's out here crazy, doing all these drugs. 'Cause I didn't get into it just to do that. And I found out that I put more time into doing drugs and partying than I did making music.

Did drugs ever help your creativity?

Definitely, but I wouldn't say go out and try it. For me starting off, I was just adventurous. I was trying different stuff. LSD was probably the culprit for opening my mind to anything and everything possible: I mean the colors, the clothing, the self-expression, the whole love-and-peace thing. It had to be in there, but what I was doing helped bring it out even more. It pumped it up faster like a time traveler. ... It was the trip of a lifetime, and I think it worked for me. I felt good about it.

Bootsy Collins, 1978, a year before the plane incident that led him to quit drugs. Credit: Fin Costello/Getty Images |

What made you stop taking drugs?

The motorcycle accident and the mother slap. And the other part was in 1979, I got on the SST [supersonic transport plane] going over to Europe. I had been wanting to fly on that thing. They had just came out. Everybody was telling us how quick you get there, so I had wanted to fly it. As soon as I got on it, 45 minutes into the flight, we lost all of the engines. So you're talking about somebody who's scared to death, man. Then we hit the sound barrier, and you just heard this big boom. I'm sitting by the window, 'cause I always sit by the window over the wing, and as soon as I heard the boom, I saw big flash of fire come from one of the motors. We were going straight down. You ever seen a plane coming out of the air? And not only that, I had just come back from the movies watching Jaws. I was like, "Oh, my God, Jaws, I'm coming to see you."

Now put that together. OK, I'm gonna crash. Then if I ain't dead, Jaws is gonna eat me. And then one of the engines kicked back in and we were able to fly back to New York sideways. It was a crash landing, but we made it. And that was one of the incidences that helped me come off of everything I was on. I made all these promises to God, like, "If you get me out of this one, Lord, help me. I promise I won't take no more." I stayed off planes until I got with Deee-Lite in 1991. Everywhere I went between those times it was bus, a train or boat.

I kept saying that for a while that it started like me crying wolf and then at some point I had to get serious. Whatever point that was, I throwed all my drugs away and I stopped taking them. That was in, like, '84 or '85. That's when it started to become clear what I needed to get back to, which was the music.

That will definitely turn your life around.

Yeah, it did. And I'm thankful. A lot of things that we think are negative to us help shape our lives. Like the thing James [Brown] was doing when he was saying I wasn't on it. That was a negative thing and that was why he was doing it to me. It helped shape my life and make me better. A lot of things come at you in a negative way and it depends on how you accept it and respond to it. It can make you a better person.

What lesson did you take from that that you rely on today?

I just wanted to play in the band. I didn't want to lead the band, because it took too much. All you wanna do is have fun with the people, and then it gets thrown on you to do this. It's like, "Man, all I wanna do is just play music for the people. Is that so hard to understand?" You gotta come up with a balance, because you have to do it all. I had to step away from it to find out how to do it. And I'm still finding out. It's something that you never really grasp.

|

|