| |

Taken from British GQ (Aug 07, 2017)

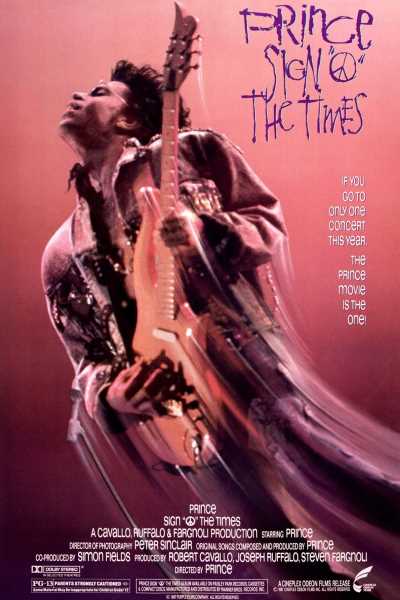

Prince’s Sign O’ The Times: celebrating 30 years of genius

GQ looks at how Prince’s album Sign O’ The Times confirmed his genius and became the most important album of its generation

by George Chesterton

Credit: Jody Todd |

Thirty years ago, Prince released his ninth album, a collection of extraordinary songs that became the greatest record of its generation. The pop prodigy's postmodern magnum opus obsessed with sex, death and faith remains a milestone of Eighties culture – and the late singer's ultimate legacy

The Eighties were not a decade to be trifled with. By 1987 they had reached both the zenith and nadir of their tasteless excess and exuberant pomposity. They were, however, the last decade to have a truly distinct identity: their own colours and sounds, a design ethos, their own internal coherence and newness. The years that followed do not share the bookended unity that make it easy for us to sense when one era ends and another begins.

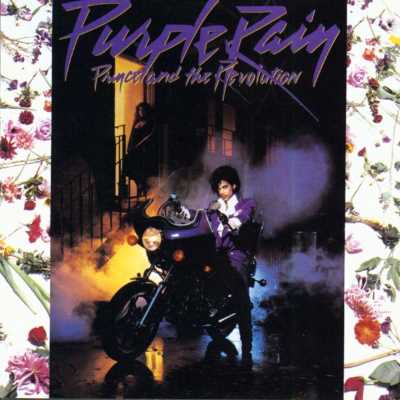

The Eighties were also the decade of the mega-album. Few of these giant records represented an artistic high, but rather embodied the total victory of corporations over the industry. Michael Jackson's Thriller began this phenomenon in 1982, followed by Bruce Springsteen, Madonna, Dire Straits, Whitney Houston, George Michael and U2. It was an exclusive club with ten million album sales as the minimum price for membership. Prince signed up with Purple Rain in 1984.

Credit: Jody Todd Credit: Jody Todd |

Thirty years ago, Prince released another album (his ninth). It did not sell as well as Faith or The Joshua Tree, and nowhere near as well as Purple Rain, but it's not easy to find anyone around in 1987 who does not agree that what he wrote and recorded eclipsed all his contemporaries. Sign O' The Times was much more than the career triumph of a musical magus. The sheer Eighties-ness of the Eighties can be so suffocating it is difficult for its culture to survive unscathed or untainted - but Prince made the Eighties sound good. Really, really good.

Sign O' The Times is the double album that confirmed Prince's greatness and signalled his slow decline (though no one knew it at the time). It coincided with yet another step back from the outside world and his retreat to the Paisley Park complex being constructed in Minneapolis. Prospero was on his island. It's ironic that Sign O' The Times was a calling card during his battle for creative independence, because if it had not been for the meddling of the dreaded Warner Brothers - against which he would wage a long, seemingly futile, conflict - the album may never had made it out at all.

Of all the losses during the festival of death our fragile psychologies constructed in 2016, Prince is the one that still upsets me. I have a terrible habit of listening to music and saying, "It's all very well, but it's not Prince, is it?" I know it's a self-defeating tick, but there you go. He was, no doubt, a distillation of James Brown, Jimi Hendrix, Sly Stone, Marvin Gaye, Stevie Wonder, George Clinton and Rick James, yet these influences do not diminish him - he remains ineluctably Prince. Conversely, no Sign O' The Times means no Outkast, no Pharrell, no Kanye, no Drake and no Frank Ocean.

Credit: Rex / Shutterstock |

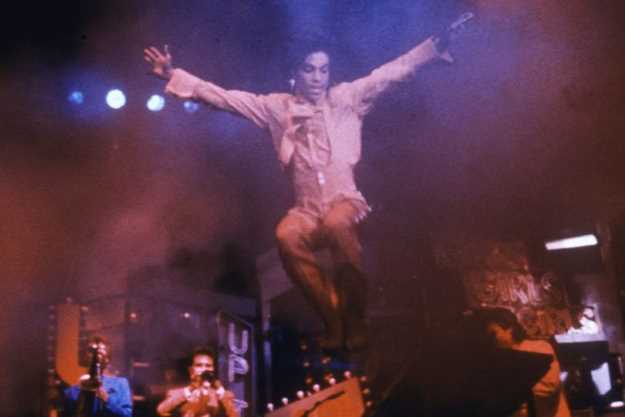

Prince was 19 when he released his first album, For You, in 1978, a showcase for his extraordinary skill and self-possession. Among the Minneapolis scene he led, he earned his reputation as a workaholic and perfectionist, qualities that would take him through the Eighties in a haze of nonstop writing, recording and performing, with hundreds of unreleased songs accumulating in the famous "Vault".

Prince followed For You with three more albums of middling success, developing his hypersexed androgyny and rock/soul hybrid until 1982 when he had his first big hits from the album 1999 (no major label today would indulge an artist for four relatively unsuccessful albums in a row). Minneapolis is a predominantly white city, so he was more exposed to rock than most African-American children. That mix bore fruit in the film and album of Purple Rain, which dominated American then global pop culture for an entire year in 1984, allowing Prince to lead his band, The Revolution, into the under-appreciated psychedelia of Around The World In A Day (1985) and the crystalline pop of Parade the following year. But there was always someone who was disappointed: his record company (and most of his newer fans) wanted a second Purple Rain; much of his black audience thought he was becoming too white; polite society was uncomfortable with his prurience and sexual ambiguity.

The first wave of fresh songs in 1986 came to be known under the umbrella of Dream Factory (although other band members recall another project called Roadhouse Garden), a continuation of their chart-friendly pop with increasing input from guitarist Wendy Melvoin and her musical (and one-time actual) partner, keyboardist Lisa Coleman. It was Prince's fear of losing control that led this project to be abandoned. During the Hit N Run/Parade tour, cracks widened between Prince and other members of The Revolution, especially Wendy and Lisa, who resented the imposition of dancers Prince had added to the lineup. This tension was not helped by Prince's engagement to Wendy's twin sister, Susannah Melvoin, also a backing singer with the band. Keyboardist Matt Fink told biographer Matt Thorne, "Wendy and Lisa didn't want to quit. It was a shock when he got rid of them and [drummer] Bobby Z in one fell swoop. I tried to dissuade him."

Aids, heroin, gangs, disasters – he was a pop Caravaggio fetishising the apocalypse

Prince's need to distance himself from the past is evident in his 1986 side-project Camille, in which he assumed an androgynous alter ego, recording his vocals at a slower speed then speeding up the tape to feminise his voice (an old trick of Clinton and Wonder). The electro-R&B songs were a calculated move away from the pop of The Revolution. The idea for Camille came from the 19th-century journals of the French hermaphrodite Herculine Barbin, who was in vogue among American Francophiles (of which Prince was one) thanks to the writings of philosopher Michel Foucault. Like Dream Factory, this would become one of the building blocks of the near-perfect album to come. Prince felt able to shelve Camille as easily as he retired several albums' worth of material with The Revolution. Producing so much music meant he could always move on to something new - there was no need to see everything through to the end. For him there was no end.

Yet another Prince project in 1986 was a high-concept rock-funk opera called Crystal Ball, and the song of the same name and the wreckage of this idea did find its way onto the next list of songs he wished to release. It's worth hunting down the original eleven-minute version of the song "Crystal Ball" to get an idea of where Prince was at the time. It illustrates his ambition, with ominous synth-funk riffs, jarring jazz interludes and classical allusions interlaced with spoken word passages and apocalyptic sound effects. It's not your average Eighties pop song. Prince's arranger, Clare Fischer, orchestrated this abandoned epic and other lost tracks (as the only associate permitted to work on his music without interference, Prince refused to meet Fischer, preferring to send him material like a pen pal) but his efforts survive on only one song from Sign O' The Times, "Slow Love".

It's impossible to know whether Roadhouse Garden, Dream Factory or Crystal Ball the opera were ever fully realised ideas for Prince, or if these were just song titles that became associated with concepts for convenience's sake (this vast range of material was recorded in seven studios in LA and Minnesota). In late 1986, Prince finally presented Warner Brothers with a triple album made up of material from all these projects called, confusingly, Crystal Ball. The company baulked at the idea of a ruinously expensive triple LP, especially after the underwhelming sales of his previous two records. Prince, reluctantly, cut seven songs to reduce it to a double LP, while embellishing others to produce his first official solo album since 1981's Controversy.

Being prolific is no guarantee of quality (1986 is the year in which the myth of The Vault was born) and a mind overrun by ideas for songs of every conceivable genre, design concepts, film scripts, dances, costumes and collaborations is prone to a lack of focus as well as great productivity. Sign O' The Times is the rescued strands of his consciousness, brought into one coherent work that he had not even conceived in that format until Warner Brothers rejected his first proposal.

Credit: Rex / Shutterstock |

Sign O' The Times is really a record of two instruments. In an act of self-sufficiency and bravado, Prince turned to the defining technology of the period which, for lesser talents would - and did - scuttle their music at the bottom of the Eighties ocean. In his hands they created something more compelling, darker and stranger. Not content with mastering guitar, bass, keyboard and drums, Prince became a virtuoso on the Fairlight CMI sampler and the Linn LM-1 drum machine as well.

What Prince would do with them is clear from the title song that opens the album. He used the stock sounds of the Fairlight, rather than samples, and twisted and burnished them until they became his alone. The famous opening bassline of "Sign O' The Times" deserves its reputation as bleakly beautiful noise - jarring and plastic but full of foreboding. It is one of the only times in his career that he looked outward beyond his immediate kingdom. Prince is rarely talked about as a great lyricist - though he is an underrated one - but the words are as unsettling as his music. Like a dark reflection of "What's Going On" he sings, "A sister killed her baby 'cause she couldn't afford to feed it/ And yet we're sending people to the moon." Aids, heroin, gangs, natural disasters, the Space Shuttle Challenger accident - he is a pop Caravaggio fetishising the apocalypse, as he had before in "1999", "Let's Go Crazy" and "Crystal Ball" and introducing an album layered with the chiaroscuro of sex, death and faith. And it's an opening shot that must have put the fear of God into his rivals.

Prince believed he was a protagonist caught in a cosmic war between good and evil, waiting for the end of days

Of course, this is meant to be the latest album by a global pop star, so Prince brings things back with the upbeat "Play In The Sunshine" and the syncopated call-and-response of Camille in "Housequake". He follows that with the album's second masterpiece, "The Ballad Of Dorothy Parker". Amid the intoxicating, humid lyrics about a man meeting a waitress who tries to seduce him, it's the musical vision that really holds you. Prince manipulates the drum machine with an astonishing deftness and control, effectively playing a continuous drum machine solo. The gnarled keyboard sounds he ekes out of the Fairlight unnerve, while the voices of these characters narrate, whisper and tease their way around this most lugubrious scenario. Like "Play In The Sunshine" it ends with a "Prince coda", an extra couple of bars in which he drops in some unconnected or unfinished musical line. It may not seem like a big deal, but it shows Prince's commitment to dazzle, attaching seemingly throwaway musical phrases that add layers of value and interest to everything.

On "It" he sings, "I think about it all the time." No shit, Prince. "It" seems little more than a chant to carnality, but he smartly allows space for the song to build without overloading the instrumentation (it contains the classic Fairlight "stab", one of the Eighties most ubiquitous effects). Prince is, as usual, insatiable and ashamed, a push and pull that dominated his work until he became a Jehovah's Witness around the turn of the century. However his feelings about sex evolved (sex as sin or life or both), he had always been a milliennialist, a protagonist in a cosmic war between good and evil waiting for the end of days. It might be hokum, but for someone with his volcanic creativity it probably helped him make sense of the world.

|

"Starfish And Coffee" is a slice of McCartney-esque levity, a nursery rhyme written about a school classmate of Wendy and Susannah Melvoin (one story is that the girl used to sing "starfish and pee-pee"). The big band sound of "Slow Love" further mellows the mood before "Hot Thing", a pounding electro-groove held down by a Fairlight bass sound. This incidental detail shows Prince at his bravest - an entire song anchored by a single atonal note that never changes even when the chords do. It features some suitably filthy saxophone by Eric Leeds and a lot of screaming. Nobody screams like Prince and, even though it seems serious, you feel sure he knew how funny it sounded.

Don't bother looking for anything profound or interesting in 30 years of Prince's gnomic public utterances (believe me, I've tried). He dismissed critics as "non-singing, non-dancing, wish-I-had-me-some-clothes fools" and the only thing he was clear about was that in interviews he was never clear, employing platitudes and nonsense rather than engagement. But fans never felt that distance. Many of the girls I grew up with were obsessed with Prince, but it was not as a traditional pin-up. The female fans I knew felt a deep connection with him, as if he understood them in a way no other star could. Although he possessed the lust of a satyr, his lack of machismo made him a less threatening - though no less desirable - idol and much has rightly been made of the help he gave so many women during his career (my favourite song by someone else is his "The Belle Of St Mark" by his brilliant drummer Sheila E). The Sign O' The Times engineer Susan Rogers said, "I'd like to point out his generosity of spirit with regard to women. For all of his love of sex, Prince never approached women as a conqueror or a predator."

‘If I Was Your Girlfriend’ is Exhibit A in the case of Prince vs Everyone Else

Some of the best songs Prince ever wrote were about Susannah Melvoin (including the rarely heard "Go" and "Empty Room") and there are at least four songs on Sign O' The Times about his muse: "If I Was Your Girlfriend", "Forever In My Life", "Strange Relationship" and "Adore".

One of these begins with the sound of an orchestra tuning up, then a street and market, then a wedding march... "If I Was Your Girlfriend" is exhibit A in the case of Prince vs Everyone Else. It is probably the most emotionally complex hit single ever released, with Prince turning the conventions of a corny slow jam on their head. The most common interpretation of the origins of this extraordinary song are that Prince was jealous of Susannah Melvoin's closeness with her sister Wendy, and here he begs to share that intimacy by proposing his own metamorphosis. He becomes - all at once - the worried boyfriend, the manipulator and seducer, the hermaphrodite Camille, the "girlfriend" and, most bizarrely of all, perhaps even Wendy herself. He inhabits these multiple personalities in the lyrics: "Would you run to me if somebody hurt you/Even if that somebody was me?" The complexity is pushed even further by his multitrack backing vocals, all at different pitches. This being Prince, it suggests physical intimacy as an expression of something deeper and ends abruptly, unresolved, in the middle of a line.

Though not part of the Camille project, "U Got The Look" sees the character return to spar with Sheena Easton in the album's most obvious, most fun and biggest single, while Prince takes up another short story with "I Could Never Take The Place Of Your Man", a song rescued from an earlier 1982 session and featuring the only true rock guitar solo of the album. What makes an artist great is not ability but taste. Prince had more ability than anyone, but he could have spent his life making prog-rock symphonies about sci-fi goblins and no one would have cared. Taste is knowing when to slow down, speed up, go soft or go loud, knowing when a touch says more than a shove and a whisper more than a scream. Compare it with the preposterous poodle rock of the same year and it's easy to see this line being crossed with abandon by almost everybody else.

Getty Images |

Even though it's followed by the semi-live "It's Gonna Be A Beautiful Night" (one of The Revolution's last performances) and the soul ballad "Adore", it often feels like the album's obvious climax is "The Cross". It's such an overwhelming experience by preacher-man Prince that when he sings, "Don't cry, He is coming" it could make even the most fervent nonbeliever consider some old-time religion. "The Cross" works in mysterious ways because, having portrayed and punished himself as a sinner, Prince's plea for salvation becomes even more potent. He is the perennial prodigal son, breaking up with God to make up with God.

I remember 1987 as an unsettling year punctuated by disaster: the Zeebrugge ferry, the Hungerford massacre, the King's Cross fire. A Conservative government had a record high 50 per cent support in the polls and luxuriated in another landslide general election victory. In the US, Ronald Reagan was playing hardball with the Soviet Union and keeping the nightmarish threat of nuclear war alive. I also remember it as the year everyone I knew learnt the words to Sign O' The Times. Today, it's still box-fresh every time you listen to it. "I could say anything at that time," said Prince.

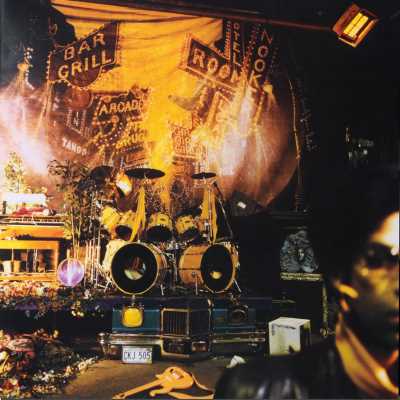

It is not a concept album, but more like a piece of postmodern architecture, reflecting how Eighties styles converged in a distinctive and sometimes brazen new way in art, design, film and TV. The album cover was suitably mysterious, with only part of Prince's out-of-focus face in the foreground and a seedy stage behind, the drums perched on an old Pontiac Grand Prix, everything in peach and black (his designated colours for the project). "Prince looks at all his music, in his whole life, as a movie, and everybody who's involved with him on whatever level is a character in his movie," said Eric Leeds.

It is easy to forget that this was a major album by one of pop music's biggest global stars, not some experimental outrider. What was the competition? Rick Astley? And 1987 was the year the wheels came off pop music in Britain, with adverts driving a rash of tired Sixties soul rereleases. In the US the big beasts remained, but more troubling for Prince was the start of house music and the proliferation of hip hop.

After Sign O’ The Times, in striving for freedom, he found himself trapped in a prison of his own making

The bludgeoning libido of The Black Album was recorded then ditched immediately after Sign O' The Times, its reputation as a great lost album undermined once it was heard in full. Prince supposedly abandoned it because he thought it was "evil". It seems he was being overwhelmed by the weight of his own concupiscence and complained of a spirit called "Spooky Electric" amid rumours he had himself been spooked after a bad experience with ecstasy. His tenth official album, Lovesexy, was him turning away from the darkness and into the light. He was never quite the same again.

Getty Images |

Prince always had an uneasy relationship with hip hop. He felt threatened by it, both as a style that would overrun his territory and as a sign of his own vulnerability and age. He regularly turned down requests for permission to sample his older work, his attitude determined by his religion, commercial paranoia and an increasingly eremitic existence in Paisley Park. "Some of these acts I really dig but I don't want my music used that way," he said in 1997.

Can it be coincidence that, as so often happens to great men, the retreat to Xanadu brings about a kind of madness in which awestruck acolytes exist only to serve - to bend to the will and whim of their master - and that the achievements of the past become impossible to repeat? That's not to say Prince was a tyrant, but that, after Sign O' The Times, in striving for freedom he found himself trapped in a prison of his own making. By the late Nineties it seemed Prince wasn't quite Prince any more. He was like a Japanese soldier, still fighting the last war.

Susan Rogers says, "Prince was smart enough, as a young man, to know that he'd need to let people in if he wanted to have a long career, so he did it. But, to the outside world, he appeared as a big enigma."

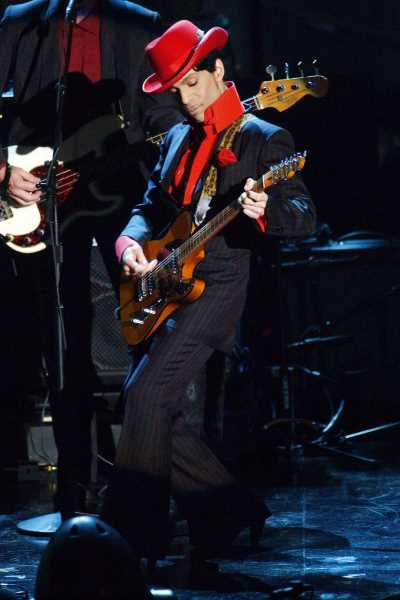

What is left is art and art endures. At his induction to the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame in 2004 he said, seemingly unaware of the irony, "Too much freedom can lead to the soul's decay." Then he went on to not just steal the show but take it, frame it and mount it on his wall with his embarrassingly brilliant guitar solo on "While My Guitar Gently Weeps".

By today's standards, Sign O' The Times may seem a cold album. But all things being cyclical, Prince and the plastic, superficial Eighties followed the sincerity of folk-rock and the ideological purity of punk. In this context, Prince was the successor to David Bowie, in that the art and artifice were the point. Heart for heart's sake was not an issue. It was the ideas that mattered. Now we value emotional nakedness above all else, in a culture where workaday honesty is judged to be "real" while around us songs, radio, TV and films become reflections of Facebook status updates.

He was different then and he's different now. He is just different. And Sign O' The Times is as wondrously, deliciously different as he ever got. Prince believed he was engaged in a cosmic war between good and evil, but for us his most important fight was against an evil somewhat closer to home. The evil of banality. Thankfully, he won.

|

|