| |

Taken from PopMatters (July 29, 2002)

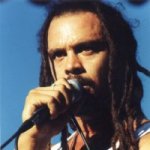

PLAYING BALL: SPEARHEAD FRONTMAN MICHAEL FRANTI TAKES TO THE STREETS

by Simon Warner

"If you don't remember the past, you can forget the future."

- Spearhead on Chocolate Supa Highway

In the side-street outside the club, as the shadows begin to stretch, a cluster of young men kick a football back and forth. It's a cool June evening in the city of Leeds, a sharp northern English breeze mocking the notion of mid-summer. A World Cup hangover, England recently ejected, tinges the scene. Yorkshire voices -- broad, hard, boisterous -- scrape as the ball bounces from head to knee in the impromptu practice session. In the side-street outside the club, as the shadows begin to stretch, a cluster of young men kick a football back and forth. It's a cool June evening in the city of Leeds, a sharp northern English breeze mocking the notion of mid-summer. A World Cup hangover, England recently ejected, tinges the scene. Yorkshire voices -- broad, hard, boisterous -- scrape as the ball bounces from head to knee in the impromptu practice session.

But one figure, rising to well over six feet, lends an eye-catching ingredient to the gathering. Towering above his fellow players, his head topped by a tied bind of rasta bangs, his feet shoeless but balletically bobbing the ball up and down, mixing with the locals with ease, joining in the banter. They chat between the juggling. "I think you're blaming the hand of God again," says the tall man with a smile as talk turns to the dashed home hopes of the soccer tournament.

Michael Franti must be the one, the only, popular music performer on earth who joins in with a street kickabout, an hour or so before he's due on stage. ("I love soccer," he confesses a little later). Spearhead, his diamond of a band, are about to play a warm-up gig prior to a tour that will take in festivals and gigs around the UK and Europe. But their frontman could be just any old punter, any old out-for-the-nighter, drifting from the hub-bub of the bar to share his footballing skills. Michael Franti must be the one, the only, popular music performer on earth who joins in with a street kickabout, an hour or so before he's due on stage. ("I love soccer," he confesses a little later). Spearhead, his diamond of a band, are about to play a warm-up gig prior to a tour that will take in festivals and gigs around the UK and Europe. But their frontman could be just any old punter, any old out-for-the-nighter, drifting from the hub-bub of the bar to share his footballing skills.

Yet Franti has made a life ignoring conventions. Maybe it stems from a formative childhood, a black boy adopted by white parents. Maybe it arises from an unwillingness to merely regard music as an frippery, an entertainment, merely a dramatic gesture. His work, a rich, warm synthesis of rap and soul and reggae, R&B and funk, jazz and latin, is a potent elixir in itself, but it is the lyrical manifesto spicing the brew that has left record company executives edgy and made extended relationships with the mainstream industry difficult to sustain.

At the same time, Franti eschews the cumbersome bravado of rap culture: while Snoop and Dre, Ice T and Ice Cube, spent years firing searing broadsides at the establishment, they, like Elvis Presley and James Brown, Jagger and Rotten before them, were eventually assimilated. Even gangsta could ultimately be commodified.

But Franti, in all his several guises -- the Beatnigs, the Disposable Heroes of Hiphoprisy, Spearhead -- has determinedly avoided the predictable battle-grounds. This gentle giant, like, say, Christ before him, says difficult, challenging things in a quiet and literate fashion: that combination of insight, intelligence and incision appears to unnerve the establishment. Liberal polemic seems rather more unsettling than macho posturing. The fact that he possesses an evangelical charisma makes him all the more compelling, all the more disconcerting, depending on your point of view.

Whether it's statements on AIDS, poverty, or the death penalty, there is a refreshing directness of approach which rises above the plainer, black and white issues of race, of urban violence, of manhood, of the ghetto, which are more likely to provide headlines and soundbites for the middle- of-the-road media. But Franti can't be compartmentalised as a personification of the street wars, as a dangerous catalyst to inter-racial tensions. Rather, he has hooked up with bigger, tougher matters, not so easily pigeon-holed or stereotyped -- often controversial civil rights issues that span communities, cross states and national boundaries, rather than become entangled in the verbosity of older power struggles.

In an impressive sequence of widely acclaimed recordings, the most recent under the Spearhead banner, including 1994's Home, 1997's Chocolate Supa Highway and 2001's Stay Human, he has explored a broad range of topics -- the questions raised by Aids on songs like "Positive" and "Do Ya Love", his cultural heritage on "Dream Team" and "Red Beans & Rice", and the plight of the poor on "Crime to be Broke in America".

Last year's CD, his most rounded and sustained collection to date, was an ambitious song cycle presented as fictional radio programme. An independent phone-in station explores the political machinations surrounding the death penalty as a black activist faces execution. On-air conversation dramatises the interchanges between the politicos and the community while a dozen new Franti compositions lend commentary and counterpoint to the debate.

As darkness falls, as the gig nears, as the football bumps and bobbles over the high fence of a nearby building site, Franti shakes hands with me and we begin to talk. I suggest we go inside but he says the noise is too great. We look around. Among the stacked breeze-blocks of the construction project, we sit. "We can improvise a studio," he says with an endearing enthusiasm. His wife Tara, clad in a Brazil tracksuit top, and one of his two children, Ad?, join us for a few moments to say hello. I ask him what it's like to be back on this side of the Atlantic, about to take his group on the road.

PopMatters: How does it feel to be returning to Europe and embarking on a summer tour?

Michael Franti: I feel a great a sense of freedom In what I do. One of my definitions of freedom is self-discovery, every day I feel I'm discovering something new about who I am and what my music is, where I fit in the world. I feel very fortunate that I have been able to do this since 1986

PM: Do you feel that some of the commercial hassle that has haunted you to a degree over the years has that disillusioned you or made you a stronger artist?

MF: I feel blessed because most of the musicians I know don't get to go to Europe and don't get to do gigs even in San Francisco, where I live. Most of the musicians I know are probably more talented, have probably practised more than I have. Most musicians don't have the chances that I do. It's the rarefied few, 0.2% of all musicians, that sell a million units, so I feel really happy to be a working musician.

PM: Do you feel sometimes that your messages are too difficult, too indigestible, for the mainstream to really taken on board? Do you feel you are saying things that are maybe uncomfortable for the mainstream record companies?

MF: My messages are often awkward and indigestible for some people but I don't feel it's the people's fault. I feel it is my responsibility, my goal, to try to make difficult messages easy to understand and that's what my craft is. Like we mentioned earlier, with literature, it's the same thing. You are constantly trying to edit your words down and be brief, so you can get some very complex ideas and emotions, across in a simple way. That's my search, that's my journey, as a craftsperson.

PM: A big question you will have been asked many times before but perhaps you'd try to answer it. Can music change things?

MF: Well, I don't know if music can change the world overnight but it can help us make it through a difficult night and sometimes that's all we need, just to make it into tomorrow. You know something, I was thinking about Bob Marley's music. If you read the history of Bob Marley and you study him as a person, he wasn't perfect - he had a lot of children outside his marriage, he did a lot of things which were a little gangster-ish in terms of getting his records played in Jamaica, he had his enemies, he wasn't a perfect person. But if you listen to his music, his music inspires us to be our best. That's what we get out of it and that's what I get out of it; when I hear that music and I think, man, and I really want to start to be virtuous and be strong and be a good person. And so I think that's one way that music does really help to promote changes; it's a catalyst for our lives and it's helps us to deal with our emotions.

PM: You're still living in San Francisco you say?

MF: Yes, I grew up in the Bay Area, in Oakland.

PM: Is San Francisco still the right environment to forge a creative space, a place where you can create your work?

MF: I think every environment is the right environment! That's what we should be doing!

PM: Are you planning to stay around the Bay?

MF: Yes, it's my home I'm raising my kids, with my wife. San Francisco is a haven for misfits and weirdos and I'm both of those things. I fit in really well!

PM: Did you see that Richard Florida report that's come out in the last few weeks in America and had emerged in Britain recently, about cities not needing shopping malls and conference centres, they need gays and bohos, creative, artistic and ethnic communities, to stimulate commercial good health.

MF: I haven't seen that; I don't know much about marketing, but I know that San Francisco has those people in abundance. I really love San Francisco because of its diversity and that's what people are maybe saying: people like to be around diversity and see the colours. San Francisco, when I first moved over there in the early Eighties, I was startled because I grew up in a pretty conservative family. I grew up in a situation where my parents were very kind of closed. My father was an alcoholic so that kept him closed in a whole different kind way. I was surprised to see gay people in the street.

Then, when the AIDS crisis came about in 1986 I saw people who were friends of mine through music and the art world, whose parents had abandoned them because they came out of the closet. They were suffering through illness and death alongside of their lovers, who were taking care of them and cleaning their bed sores and holding their hands on the street as they were going blind and ultimately shrivelling up and dying. And I started to realise that it's not so important who you choose to love as do you choose to love? I wrote a song about that 'Do You Love' which was inspired from that.

PM: Just to move on to literature and the way it may have affected you. You had a band called the Beatnigs which obviously played on the black thing and the Beat thing, and you made an interesting album with William Burroughs. What does the Beat Generation, what does the Beat movement, reading, poetry, the novel, mean to you? Are they things that have shaped your own creativity?

MF: Yeah . . . when I was a kid -- you know my parents were white, I was adopted -- one day I came home from school. I was about six years old, and some kids had called me a bad name. I was really hurt, I was crying, I was scared, and my mother was, like, what did they call you? You could not curse in my family, I would have got my mouth washed with soap and slapped. So I didn't want to say the word. "Was it the f-word, was it the s-word? What was it?" "No, it was the n-word, it was nigger". I didn't know what that meant, but I knew it was a bad word. My father and my mother said sticks and stones may break your bones but names will never harm you.

Since that time, in my life I've been in fist fights and had things thrown at me at concerts, been battered and bruised and stitched up, and those scars have always healed but the scars that have really stayed with me and affected me are the words that people say to me. But as I grew up, as I made it through high school, I did not really start reading until I got into university in San Francisco -- I got a scholarship to play basketball -- and through that I had some really good teachers in my first year at school and they turned me on to reading. And through that I found that words had the power to hurt people but they also had the power to heal people, and that's what got so into writing, so into poetry, so into story-telling.

A lot of the songs I write are narratives -- I love words and I am really healed though reading and inspired by reading. So many of the songs that I write are inspired from phrases that I come across in books. Sometimes people put together words in a clever way and sometimes I will draw on those words to use as lyrics in my song, as I try to find a spark.

PM: Are there particular writers or poets who you might name-check as influences?

MF: You know who I really like as far as poetry goes and that's (the Nuyorican poet) Saul Williams. We have become buddies and it's like there has never been in my life a contemporary person who I felt so in tune with the higher level of wordsmithing. We had a chance to tour together, hang out together, and I'm just really in awe every time I'm around him. I really hope we work on something together. The way that he thinks and the way that he writes is really great. And it's neat -- I always read about Jack Kerouac and the Beat Generation, Lawrence Ferlinghetti and living in San Francisco you are around all that history, but it's never been that I had a contemporary who I felt I could share this kind of thing so having Saul has been special.

PM: Have you written prose or been tempted to write it?

MF: No lately I have been moving further and further away from just narrative writing, because I have just been playing guitar, so I've gotten interested, at the moment, in the craft of the three minute song, I'm really listening to Woody Guthrie and the Beatles who I've never really ever listened to. Nut then I'm also listening to the way Doug E. Fresh writes, and the way that Biggie Smalls writes, Slick Rick, really concentrating on pop form and simplicity, brief writing, but being able to tell like a very elaborate story.

PM: When are you planning to release more new music?

MF: We have been working on a new record. We started working on it in February. We started writing it then. In April and May we went into the studio, working with Sly and Robbie on some of the tracks. At the end of August or September, we'll finish it, then we'll put out a single in the fall and the album will come out at the beginning of the year. The working title is Everyone Deserves Music.

Everyone deserves music! That seems an appropriate point to end, as we're looking forward to catching your gig tonight. Thanks, Michael and hope you enjoy your show.

The ball has been recovered. The local lads are back in action. Michael Franti cannot resist their invitation to return. "Don't get injured," I say. He laughs loudly and re-enters the friendly fray.

- 29 July 2002

|

|