| |

Taken from Pitchfork (October 06, 2015)

Do It All Night

The Story of Prince’s Dirty Mind

by Michaelangelo Matos

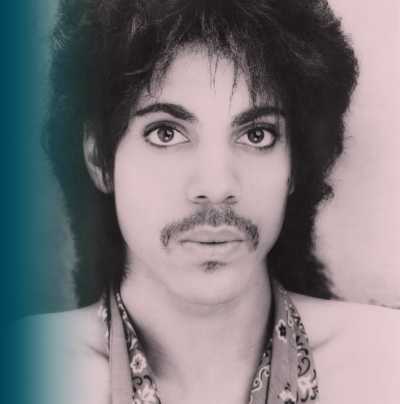

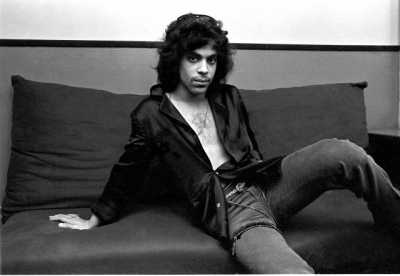

Photo by: © Pictorial Press Ltd / Alamy Stock Photo |

This article appears in the eighth issue of our print quarterly, The Pitchfork Review, which will be available at stores across America on October 26. Subscribe here.

It’s not entirely your fault if you don’t quite understand why Prince was such a big deal in the 1980s. In the digital era, the Minneapolis auteur has made his catalog relatively inaccessible, recently removing it from mainstream streaming services in protest of their underpayment. The strategy is principled and laudable even as it contrasts with prevailing realities, which means it’s très Prince—done with the belief that his legacy should be regarded his way. But whereas that same kind of stubborn, altruistic conviction often backfires for him now, it once made Prince the most exciting artist in the world.

When Prince signed to Warner Bros. Records in 1977 at age 19, his contract not only called for an unusual degree of creative control—he was to write, produce, and play every instrument on his recordings, à la Stevie Wonder—but also explicitly stated that he be part of the label's pop roster, not its R&B one. This distinction would shape the entirety of his career to come.

His first album, 1978’s For You, was all falsetto and ambition. His grasp was sure, but the material wasn’t quite there yet. Even so, the song “Soft and Wet” raised a few eyebrows: Stevie may have been a 12-year-old genius, but Prince was a teenage prodigy delivering an ode to pussy. The track’s canny combination of coy lyrics, tricky drumming, and layered harmonies served notice: not only could the kid play and sing, he could hear.

A year later, everything changed. Critic Chris Herrington once called 1979’s Prince the greatest teen-pop album ever made, and it’s difficult to argue the point (though “Bambi”, in which a crazed-sounding Prince tells a woman he wants to sleep with to renounce her lesbianism over a heavy guitar solo, is not quite high-school fare). “I Wanna Be Your Lover” crossed him over to pop and led to an infamous “American Bandstand”appearance in which he fucked with host Dick Clark by refusing to speak, instead holding fingers up to indicate numbers and smirking the whole time. Prince’s persona was that of the Avenging Geek—with the proviso that he would be much more capable in bed, since that was pretty much all he sang about.

Prince circa 1980. Photo by© Deborah Feingold/Corbis. |

For years, Prince had played with junior high and high school classmates from Minneapolis’ North Side. The talent pool was deep, and Prince could have picked anyone. The band’s roster was male, female, black, white—a mixture clearly modeled on Sly and the Family Stone. He also cranked his guitar in concert, not just on “Bambi” but on everything. Reviewing one of his first live outings fronting the band he would later dub the Revolution, Manhattan’s Soho Weekly News wrote in 1980: "Judging by [Prince], you'd never know that Prince is anything but a rock dilettante. In concert, it's clearly his lifeline.”

This had been the case for some time. Not only had the young tyro bicycled to his local record store in North Minneapolis, where the majority of the Twin Cities’ then-minuscule black population lived, to pick up new James Brown 7”s, he had been playing hard-rock covers in bars since he was a teenager. “I’m not saying I’m better than anybody else,” he told Rolling Stone in 1990. “But you’ll be sitting there at the Grammys, and U2 will beat you. And you say to yourself, ‘Wait a minute. I can play that kind of music, too. … But you will not do ‘Housequake’”—a JB-indebted funk bomb from 1987’s Sign O’ the Times.

Prince’s first dozen headlining club shows began at the Roxy in West Hollywood on November 26, 1979, and served as warm-ups for his real coming out as a live performer: opening 42 dates for Rick James’ Fire It Up Tour in February and March of 1980. On that trek, Prince typically stayed on script: seven songs culled from the first two albums. With one major exception the following year, this was not only the last time Prince would be anybody’s opening act but one of the few times he followed a setlist so exactly for an entire tour. That creative restlessness aligned him more readily with the make-it-new sensibility of ‘60s rock than it did with ‘80s pop’s carefully-laid marketing plans.

Prince had allegedly been added to Rick James’ tour to bolster the headliner’s waning draw. "It was a rough period for Rick," Prince’s guitarist Dez Dickerson told biographer Dave Hill. "We would go over like gangbusters, because the black audience was just dying for something new.” James himself famously loathed the Minnesota imp, telling Rolling Stone, “I can't believe people are gullible enough to buy Prince's jive records.” James called Prince “a mentally disturbed young man. He's out to lunch. You can't take his music seriously. He sings songs about oral sex and incest.” James would exact his revenge—as Prince’s 1980 opening act Teena Marie told Alan Light—by allegedly stealing Prince’s programmed synthesizers and using them on his own 1981 album Street Songs, and then sending them back to him “with a thank-you card.” (Prince returned the favor when he persuaded James' date to the American Music Awards, Denise Matthews, to join Vanity 6.)

Prince responded to the pressure and tedium of the James tour by working on what would become his third album, Dirty Mind. In the BBC documentary “Hunting For Prince's Vault”, keyboardist Matt “Dr.” Fink said that Prince wrote “When You Were Mine” on the balcony of a Florida hotel room, declining to join the rest of the band on a day trip to Walt Disney World.

Rick James had a lot to say about Prince, most of it bad. In 1983, he told Blues & Soul: “He doesn't want to be black. My job is to keep reality over this little science fiction creep. And if he doesn't like what I'm saying, he can kiss my ass. He's so far out of touch with what's really happening, it makes me angry.”

Prince was well acquainted with the reality of race in the record business. Crossing over from the commercial exile of R&B—a genre acutely feeling the aftereffects of disco’s backlash—to rock's mainstream was vital to anyone in his situation, especially as a native of lily-white Minneapolis. Writer Steve Perry quoted Jimmy Jam as saying, “Black musicians [in Minneapolis in the ‘70s] were going, ‘We can’t get a job, we better make a demo tape or something and try to get up out of here.’ … Not that we had more talent [than the white musicians]; nothing like that. We just had more initiative, because there was nothing here for us.”

That situation was writ large at the dawn of the ‘80s—which is to say, Prince knew precisely how fucked he would be if he didn’t stipulate that he be treated as a pop act. This was the dark ages of R&B crossover. Billboard’s year-end 1981 singles list featured only eight black records in the Top 40; in 1979, there had been 16 (and seven black records in the Top 10). The number had halved in two years.

“The record industry provides probably the strangest example of segregation since South African apartheid—a frequent, unspoken separation of blacks and whites that subtly and insidiously damages our industry,” Prince’s publicist Howard Bloom wrote in an August 1981 commentary piece for Billboard. “If a black act's record is rock & roll and belongs on AOR radio, that's too bad. The black special markets department drops the record because it's not appropriate to black radio. And the white AOR and pop departments generally refuse to touch the record because of the color of the artist who made it.” This also worked in reverse, as Bloom pointed out: Devo's “Whip It” got little play on AOR, Devo’s so-called “natural” constituency, but went gold in part because the record had broken on black radio thanks to black radio legend and Detroit techno forefather The Electrifying Mojo, who was also the first DJ to broadcast Prince’s music to the Motor City.

Although Prince liked to kid new wave, he also saw its openness as a beacon of the future. In 1981 he told an interviewer, “Tradition at black concerts a lot of times was to wear your best clothes, to come looking really dapper. It’s not like that at our concerts. There are a lot of black kids out there, but they're like open-minded and free, and they want to have a good time.” Guitarist Wendy Melvoin told Spin that when she joined Prince’s band in 1983, “We were still seen as part of the underground. I was proud of that.”

Bloom was ready to put his ideals into action, writing in a memo to Prince’s then-manager Steve Fargnoli, “I'd suggest booking him two dates in each market: a date as a second act on the bill to a major black headliner like Cameo, Parliament, etc., and a date at the local new wave dance club … Neither date will conflict with the other.”

The reason for all this was Dirty Mind, which Jean Williams—Billboard’s founding R&B editor—tut-tutted over: “The front cover has Prince standing donned in an open jacket with a handkerchief around his neck and in a pair of black briefs. Maybe it's meant to be sexy. The back cover gets better (or worse). Prince is lying down with the same 'outfit,' however, this time you get a look at his legs and what is he wearing? A pair of thigh high stockings. The effect is one of a nude man dressed in a pair of thigh high stockings.”

Dirty Mind was not just a rock album by a black artist but one that was sold by Warner Bros. as an album, rather than simply as a hit single’s expansion pack. Dirty Mind only yielded one R&B hit (“Uptown” reached #5) and had no success on the pop singles charts. At that time, the album audience was considered very separate than the singles audience—“serious” listeners versus casual—a difference that Warners’ marketing department was particularly adept at exploiting. However, this was a distinction that was creeping toward irrelevance: Within three years, the “tentpole” album, spinning off endless hit singles à la Michael Jackson’s Thriller, would be the major-label norm. But the idea of a crossover from R&B to new wave was both viable and novel in 1980—just ask Rick James, the self-crowned “King of Punk-Funk.”

Little of James’ music—or Prince’s for that matter—actually resembled new wave’s willful primitivism. “For a lot of black people, the word 'punk' had connotations of homosexuality, and there's always that macho thing with funk,” Dez Dickerson told Dave Hill. Dickerson himself “was put off by people with no intention of knowing how to play. Then, after a while, the spirit and the attitude of it began to appeal to me.”

Prince’s new wave leanings weren’t surprising considering that he was a regular attendee as well as an onstage fixture at First Avenue, the downtown Minneapolis club that regularly showcased new wave and independent artists. (A former employee once recalled Prince being kicked out of the club one afternoon, prior to opening hours, when he was caught in flagrante with a woman in the men's-room stall.) But even early on, Prince was interested making his own scene rather than joining someone else’s; he’d let himself be marketed as “new wave” while simultaneously disdaining it. To wit: At the end of the first side of the Time’s 1982 LP What Time Is It? (one of many Prince ghost-written and -produced albums from this period) the band sneers, “We don’t like new wave!”

There’s no mistaking “When You Were Mine” for anything but a new wave song—it has organ from the Blondie/Elvis Costello & the Attractions playbook, a stiff beat, and nervous guitar. The song’s urgency was built into its structure. As the late Paul Williams pointed out, the verses keep retracting: The first verse is 12 lines, the second is eight, the third four. Each verse takes us to the chorus faster, as well as to the song’s central dozen-note riff, which is both keynote and denouement. This was increasingly essential to Prince’s shows, in which, as Dave Hill pointed out, “one song would jump straight into the next with little explanation from the stage—another punk technique.”

If Dirty Mind is the album that allowed Prince to cross over as a rock’n’roll star, “When You Were Mine” is the song that allowed Prince to cross over as a rock’n’roll songwriter. At San Francisco club The Stone in March 1981, Greil Marcus reported, “‘That was the history of rock’n’roll in one song!’ a friend shouted before the last notes of ‘When You Were Mine’ were out of the air.” The song became an instant standard; the first cover appeared in less than a year, by English power-poppers Bette Bright and the Illuminations on Korova, Echo and the Bunnymen’s label. It was produced by Clive Langer and Alan Winstanley, the duo behind Dexys Midnight Runners’ “Come on Eileen” and Madness’ “Our House” (and later, uh, Bush’s Sixteen Stone). Other great versions would come from Detroit garage-rocker Mitch Ryder, Cyndi Lauper, and Crooked Fingers, who performed it as a creaking mountain ballad.

Bette Bright’s version changes the lyric slightly: Instead of “I know that you’re going with another guy,” it becomes “I’m going with another guy”; instead of “following him whenever he’s with you,” another pronoun switch. Changing the lyric of “When You Were Mine” has happened a lot when people cover the song, and not just because the song’s narrator was a man. The original song wasn’t merely about a love triangle but an ambiguously bisexual one, the interpretation of which focuses on the line, “When he was there sleeping in between the two of us,” as well as end of the final verse: “Now I spend my time following him whenever he’s with you.” Though “Sister” was the Dirty Mind track where Prince spells it out (“She’s the reason for my bisexuality,” often transcribed as “my, uh, sexuality”) the subtle hints in “When You Were Mine” were apparently enough to keep the song off the air. Positioning the song’s narrator as even a little queer was another touchstone with the notably gay-friendly space of new wave. The lyrics’ ambiguities are clearly deliberate.

Sleeping in between the two of us: This was Prince’s philosophy in a nutshell. “When You Were Mine” set up a career of defying expectations, jostling between sacred and profane, black and white, rock and funk, good or bad—and for the rest of the ‘80s he’d take more chances than anybody in pop. “When I brought it to the record company, it shocked a lot of people,” Prince told Rolling Stone of Dirty Mind. “But they didn't ask me to go back and change anything, and I'm real grateful. Anyway, I wasn't being deliberately provocative. I was being deliberately me.”

|

|