| |

Taken from sfweekly.com (Aug 30, 1995)

Keeping It Real

Redefining hip hop with Spearhead, Ben Harper and Aceyalone

by sfweekly.com

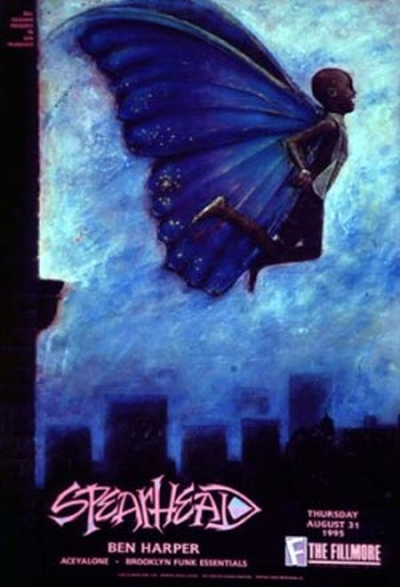

Concert Poster Filmore |

"Keep it real" scores of hip-hop MCs stress in song after song, a cliched cry that essentially translates into "keep it status quo." Though historically hip hop has been all about quick-fire evolution, the genre has grown increasingly formulaic in recent years. To mainstream eyes, hip hop means gangsta rap -- one never-ending tale of drug slangin', gang-bangin', and beeyatch-slappin'. Maybe that's why the rap market has suffered a marked decline in the past two years. Truly alternative hip hop exists, but is often disdained as some bastard child to be adopted by the college radio (read: white) crowd. As the hardcore audience fails to embrace these artists as their own, emotionally or financially, the acceptable definition of hip hop gets narrower by the day.

Michael Franti, Ben Harper, and Aceyalone are three hip-hop generation artists somewhat spurned by their peers for a steadfast reluctance to conform to easy categorization. Franti leads Spearhead, a five-plus ensemble that blends a panoply of black musical forms into a gumbo of warm, smoldering grooves. Singer/songwriter Ben Harper plays a soulful blues guitar that's hip hop in outlook, if not in sound. Then there's Aceyalone, whose stylishly cantillating delivery and thought-provoking lyrics lift him above the common rap realm. Though their individual styles differ greatly, the trio are united by a keen sense of poetry -- one learned at the knees of Run DMC and Grandmaster Flash, as well as Too $hort.

"Sure I would like more hip-hop people to hear what I have to say," Franti admits. "But it doesn't piss me off. I'm a storyteller. That's where my talent is. For me success means being able to create things, and I've been able to do that for quite a few years." True. First came his stint with the seminal if little heard Beatnigs, a Bay Area industrial outfit on Alternative Tentacles. Then came the breakbeats-meet-scrap-metal sound of Disposable Heroes of Hiphoprisy, with Franti as MC. Who was this guy rapping about Amos and Andy, AIDS, and Pete Wilson? hip hoppers wondered. Is he one of us? Outspokenly political and musically amorphous, Hiphoprisy found itself filed under alternative rock, not hip hop.

But Spearhead's debut, Home, is bridging the gap between audiences with its grooveful mix of rap, funk, reggae, rock, and jazz. Released in 1994 to critical acclaim but dismal sales, the album has been gradually picking up steam. Radio programmers may have shunned it, especially at urban stations, but MTV positioned the recent "Hole in the Bucket" Buzz Bin clip on both the Alternative Nation and rap-flavored MTV Jams segments. A grittier "Slaveship Mix" of the thoughtful look at homelessness has received heavy airplay on BET.

Franti thinks the hip-hop nation is ready for a change. "A lot of these kids are like myself. We grew up listening to Run DMC, Sugarhill Gang, all that early stuff. We were in high school then, and now we're out of college. And, you know, Onyx is cool, but we don't always want to slam and let the boys be boys. We want to listen to stuff that's mind-expanding, too."

The same goes for 25-year-old Ben Harper, who titles his second release Fight for Your Mind. "If you're gonna step, step on in/ If you're gonna finish, you've gotta begin/ Don't fear what you don't know," he sings on the title track. With a folk singer's sense of imagery, Harper grounds his lyrics in social commentary. "This album is about the fight between good and evil," Harper says. "I think it can get better, and that we can make it easier, but I don't see an end to the rate of regression taking place. I see a lot of irresponsibility, misinformation."

Harper has been pegged as a folky, hip-hop guitarist, an assessment that has as much to do with his imposing physique and fat ghetto braids as it does with his music. Though he was weaned on rap, he says it doesn't dictate his style of play. "I'm not blues or hip hop or anything like that. I love both of them, but I'm committed to the music I hear in my head. I don't want to restrict it to any one style. Music is about growth and experimentation -- it doesn't have boundaries, people do."

Nothing has been able to contain Los Angeles' Aceyalone, though. As one-fourth of the lyrically prolific and still active Freestyle Fellowship, Aceyalone helped take hip hop to realms previously explored by the likes of Mingus and Parker. The Fellowship bases their delivery on melodic ebbs and flows, vocal inflections, and jazz harmonics. What lends each MC distinction is not just stylish presentation but lyrical flows that resonate with thought and meaning. For example, in "Headaches & Woes" from Acey's upcoming solo debut, All Balls Don't Bounce, he guides the listener through the psyche of a young black man: "I got a head full of headaches, a heart that's full of woes, man/ I'm constantly singing the blues and not many people know, man/ That leaves me with a twisted view of the whole wide world as I know it/ And I guess I got no choice but to be a poet/ I guess I got no choice but to be a prophet, a griot/ A gangsta, an athlete, a bum, a nobody, a criminal, a convict, a black man, an MC." It's a far cry from the juvenile choruses of the stunts-and-blunts flunkies.

"We do poetry, jazz, spoken word," Acey says. "It's all the same thing. No limitations. It's called being open. We're just open."

Hip hop raised Franti, Harper, and Aceyalone just like it raised Snoop and the Wu Tang Clan, to diverse results. Their music underscores the depth and dynamics of hip hop, proves that it need not be constrained to a simple beat and a rhyme. "Hip hop is a culture," Franti explains. "It's the dance, it's the music, it's the clothes, it's the DJs, it's the rappers. There's the spray art, the language, the code of ethics taught. The only thing I haven't peeped out yet is what hip-hop food is, exactly. I'm sure at one point there'll be a specific cuisine," he laughs.

Spearhead, Ben Harper, and Aceyalone play Thurs, Aug. 31, at the Fillmore in S.F.; call 346-6000

|

|