| |

Taken from Bass Musician Magazine (October 1, 2013)

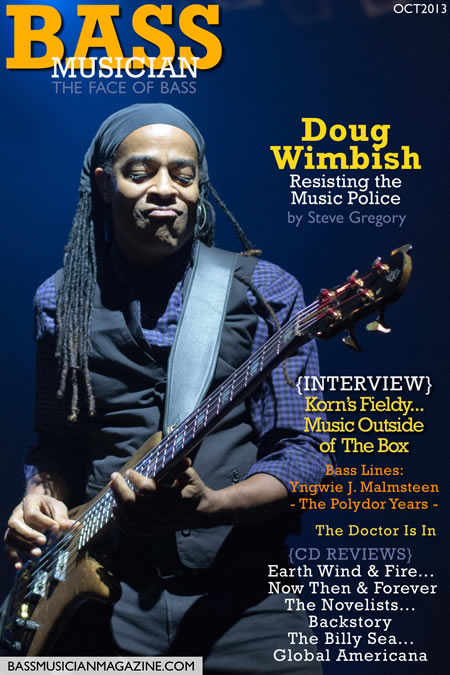

Doug Wimbish: Resisting the Music Police

by Steve Gregory

Bass Musician Magazine Cover Oct 2013 |

The music police are everywhere. Standing patrol at every industry event, YouTube post, and concert, they are always ready to jump into action. Anything outside of what has been mandated as “the acceptable” causes alarms the sound across the force, sending swarms of officers to derail artists of a different mind. Sonic intruders are belittled, derided, and beaten back to ensure that the comfort level of the masses remains undisturbed. Status quo will be maintained; innovation is the enemy.

Rather than some far-fetched, futuristic Orwellian plot, this scenario is current and real. The music police, who were once posted only in key positions within the recording industry, now have legions of self-appointed deputies patrolling YouTube and message boards to sling insults and vilify musicians who follow frequencies that are considered taboo and dangerous. To the Big Brother, musical enemy number one is the bassist who travels outside of the known, instead choosing to follow his or her own muse. Effects that alter the beloved clean bass sound, techniques that are unusual and new, and, heaven forbid, bass solos that enter the rarefied air occupied by guitarists, are reason for the music police to go into full attack mode. “Obviously a frustrated guitarist” and “that doesn’t sound like a bass” are phrases so often hurled at innovators, they almost seem cliché.

So what of the musical outlaws, the ones that hear their muse sing so loudly that they cannot help but follow the unknown path? There are some that start on their journey, but are quickly turned away, bruised and defeated. Others race across the musical sky in a meteoric burn, changing perceptions and illuminating others to new possibilities by the sheer brightness of their path. To the music police however, the most dangerous are those that have infiltrated the system and unapologetically change the way we understand music one recording, one concert, and one act of musical defiance at a time.

Doug Wimbish is one of the greatest artists of musical mischief that the bass world has known. The music police cite a list of offenses that includes the use of effects, looping, sampling, soloing, and making entire recordings that sound like they feature multiple instruments, but are made with just a bass. Doug has raised the ire of many by bucking music trends and inciting new movements in rap, rock, funk, noise, and jazz, to name only a few genres that have been affecting by his uncompromising bass sound. The problem for those that wish to impose musical dictatorship is that Doug is not a fringe player that can be cornered, threatened, and pushed aside. Rather than hiding in the shadows to create low-level shenanigans, Doug has been in the public eye with a recording career that is now entering its fourth decade. During this span, Doug has produced thousands of amazing recordings and hundreds of popular hit records. As soon as the patrols close in to capture Doug in an act of revolution, he has moved again, only leaving behind a recording that has the masses clamoring for more.

Photo by Luciana Casado |

After growing up in Connecticut and developing a name for himself in recording circles, Doug leaped into the mainstream musical scene with the group Wood, Brass, and Steel, who recorded on All Platinum Records. After two albums were recorded, All Platinum Records folded and many of those involved migrated to create Sugar Hill Records. It was at Sugar Hill that Doug founded his first of many major musical revolutions. The recordings from Sugar Hill, which included tracks by Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five, Mille Mel, and Duke Bootee, introduced the world to the energy and innovation of rap. Doug’s contributions would change the perception of bass playing and influence the entire history of rap and hip-hop. Unfortunately, Sugar Hill Records was fraught with allegations of egregious abuse of artists and musicians, which has been recently documented in the release of the movie, “I Want My Name Back”. Rather than be subject to the abuse without response, Doug took advantage of the system and developed his playing, recording, and production to a level that would lead him to even greater heights.

While at Sugar Hill, Doug partnered with guitarist Skip McDonald and drummer Keith LeBlanc. This trio was at the center of the seismic musical movement at Sugar Hill and, after leaving in 1984, would move together to London begin another era in musical advancement. In London, Doug, Skip, and Keith, along with British producer Adrian Sherwood, formed a new musical entity. While the group would grace recordings by major artists as a studio band, they would break out into their own sonic space as Tackhead. Tackhead produced noisy, artful records that challenged politics, religion, and current culture. It was during this era that Doug was given the freedom to completely stretch his sonic landscape. In Doug’s words, he learned how to, “make a record out of nothing”. No sonic territory was considered off limits and Doug took every opportunity to explore these frontiers. Two Tackhead recordings that are readily available, “Friendly as a Hand Grenade” and “Strange Things”, highlight the boundless energy that Doug brought to the music, without regard for the status quo.

While Doug was causing a clamor among listeners who were excited and in awe of his groundbreaking bass work, he also found himself in circles with major label artists. His amazing abilities and recording prowess led him to record and collaborate with Jeff Beck, Mick Jagger, Joe Satriani, Annie Lennox, Seal, Madonna, and others. Doug was able to maintain his relentless attack on bass frequencies on one side, while slowly introducing the mainstream to his talents and unique sound on the other – the perfect situation for eluding the music oppressors.

Photo by Luciana Casado |

In 1991, Doug was asked to join the band Living Colour, who was already riding the dual waves of critical acclaim and music police action with their first two releases that featured multiple musical styles and provocative song subject matter. Doug joined Living Colour and immediately impacted the band in tremendous ways. The first record completed together, “Stain”, showcased Doug’s fiery energy and innovative sounds. The recording garnered a Grammy nomination for the song, “Leave It Alone”, which was co-written by Doug and featured his effect-driven bass sound. After a second release in the new group formation, “Pride”, lead guitarist Vernon Reid disbanded the band.

After Living Colour’s breakup, Doug launched into a period of restless innovation, in a quest for new frequencies and energy. With Living Colour drummer Will Calhoun and jazz vocalist Vinx, Doug formed Jungle Funk, a unique, drum-and-bass driven trio that gained the attention of major festivals, fans, and critics. Soon after, Will and Doug formed the trance/groove group HeadFake. The 90’s were capped with Doug’s solo release, “Trippy Notes for Bass”.

Living Colour reformed after a one-off gig in 2000 that led to the release of “Collideoscope”, an album featuring an array of styles and subjects. While the group began to tour together, Doug also continued recording and playing with a wide range of musicians. These artists included Mos Def, Fernando Porto, and John McCarthy. Most recently, Doug’s calendar has been filled by a tour with Living Colour to celebrate the 25th anniversary of “Vivid”, along with writing and recording a new album with the group. He has also worked with Finnish vocalist Tarja Turunen and has reunited with Sugar Hill artists after the release of “I Want My Name Back”.

Doug Wimbish is relentless in his pursuit of sound and is passionate about the frequencies that vibrate within him. When speaking with Doug, one quickly realizes that they are in the presence of someone who has altered the bass world one note at a time, often while facing criticism for his efforts. Always one step ahead, it is not unusual to see insults hurled at his effects or techniques, only to see them adopted by others a short time later. Doug’s passion for sound is his muse and it is this song that he has followed, even when the music police were in hot pursuit.

The typical question-answer format that is common in interviews doesn’t fit Doug. He is always moving, always thinking, and always willing to share his knowledge. This interview reflects that unique style, eschewing the standard format and simply presenting topics we spoke about. As with many things with which he is involved, Doug is changing the game in every way.

Reconnecting with members of the Sugar Hill Gang and the watching the release of, “I Want My Name Back”.

Just to look back and reflect on the times and the amount of struggles that we all went through…it’s like surviving a plane crash. It’s the only way I can describe it. Getting back together with Master Gee and Wonder Boy has been a blessing. We went through a lot together. We paved the road for ourselves; we did a lot of legwork and we also paved the road for other folks to follow.

To be on the same stage, just to be in the same room and to have conversations with the guys after many years…I think the last time we had all been together on stage, prior to this year, must have been 1983, 82, something like that. A lot has happened since; the rap industry in particular has really taken a whole other course, since the mid-70’s until now. It’s just gone way past anybody’s wildest dreams. A lot of people have been blessed to have the markers that we left to follow, to be able to move forward. Let’s look at it like it was just gasses before, now there’s solid planets that exist, and a lot of the planets that exist now shine brighter than the original gasses.

To be able to actually sit and watch that documentary was bone chilling. What really got me was watching my friends watch and the response I got from them. I sat right next to Capt. Kirk from the Roots and Vernon Reid on the other side when we were watching that. These guys have known a lot of stuff that was done, but they had no idea. Their mouths were on the floor watching that movie. It’s a CSI crime scene, basically. The look on Vernon’s face, in particular, was classic, because I’ve known him so long, but I’ve never really shared these stories that much. Sometimes you don’t really know what’s happening until you see it and witness it in a certain way.

To go back down memory lane is really deep. I feel relieved and I feel empty at the same time. To see the images of Sugar Hill Records, what was left after the fire; that park bench that everybody was doing the interviews on…so much history. So much depth, you can’t possibly engage in it. All that being said and done, I look at it as a blessing to be able to finally have other people see and hear just a snippet of some of the things that took place in hip hop history.

For me, it is the beginning of a new era for us, now we’re looking at continuing and doing some new things together. It’s just funny how things happen in life; some things go full circle. Right now, I’m at a point in my life where I’m just happy to have been involved in the Sugar Hill scene that took place. Being with Mike and Guy is right now is an honor. I talk to the guys all the time. I look forward to our next encounters.

Starting out at Sugar Hill

Photo by Luciana Casado |

I look back and it all was like a flash. We went into the studio one day in 1979. We drove down there and the next thing you know, we’re in the studio. From the day we went there, we never stopped working.

Sylvia [Robinson] was trying to reach my house and we were still protesting anything Sylvia Robinson-based because we had just left Wood, Brass, and Steel. We did two records, the company (All Platinum Records) folded, and didn’t do anything with the record. It was a great record and we were all pissed off as a band. Sylvia starts ringing my mom’s house. I finally took the call and she asked if I could come down. I had heard Rapper’s Delight in a disco we played at and thought, “That’s an All Platinum record!”You know the sound of studios, like a Staxx, or Motown, or Philly International, and so on and so forth. “That’s an All Platinum record!”I heard the first four bars and told Keith [LeBlanc] that and he got even more excited about us going down there.

We initially went to Sugar Hill and we knew something was happening because when we drove back from Sugar Hill we ran right into a friggin’ tornado! A tornado in Connecticut is very rare and I said, “That’s sign enough”.

The Sugar Hill Era

Things were alive; it was an alive time. I look back now in reflection and it was almost like, “Did I play on that stuff?”It seems like another lifetime; it was going into the new world not knowing what’s happening. All the people that came through, all the sessions we did, all the people that I met. It’s not just the rappers, it’s all around. There were a lot of great engineers that came through Sugar Hill Records. So many untold stories of people that came, almost for holy water. Stewart Copeland coming in, sniffing around, seeing what was happening, right when the Police were at their height. The guys from Squeeze… A lot of guys from England were kind of interested in what was going on at Sugar Hill. They took notice before a lot of folks in America did, as far as what was going on, the culture, how we made the records, and then trying to get myself, Keith, and Skip, because we were the rhythm section for all of that. At one point, it was quoted that the three of us were on more turntables than any other self-contained band.

That being said and done, we never let it go to our heads, we were just having fun, it was a gig. We didn’t make that much money, because we were being robbed; we were being satisfied by the friendship and meeting other people that we were around. On one level the financial side of it was a crime scene, but the unity of all of us being together was beautiful and was the real payment. If I have to turn anything into currency, my currency was the friendship that we had with everybody there. People have absolutely no idea how hard we worked to pave the road. It was something that paved the road for future generations and I’m happy to be a part of it.

Understanding the impact that Doug’s work at Sugar Hill was having on the music industry

We were aware by the effect and it came in many different ways, it was a continuum. We were working a lot, so we didn’t have enough time to think or let our egos go crazy. We would go to Disco Fever on a Friday night and listen to what was going on with what Grandmaster Flash was spinning. We would take notes in our minds so we could go in and cut some arrangements for what he had played over the weekend. Then on Friday, I’d be driving back to Connecticut and I could hear it on the radio, before it even came out!That was the effect.

Then the other effect was that people used to laugh at us, they thought it was a novelty. Coming from Wood, Brass, and Steel and some of the other stuff I had done prior to the Sugar Hill era, people were like, “Why are you guys doing this? You guys are much better musicians than that!” So you had this push-pull from folks, but it was temporary. A lot of what was in people’s minds was trying to equate what we were doing with what was happening at that time with the whole funk scene. Parliament-Funkadelic, Rick James, Cameo, and Con Funk Shun were the markers and all of those folks were not really feeling it at first until “Rapper’s Delight” came out.

We would go on stage and play one song and it would be complete pandemonium for 15 minutes, so those that didn’t believe kind of got swallowed up by the wave of believers. It was like One Direction/Justin Beiber on steroids. Master Gee was 17 years old and he was that kid that was taking his shirt off and making the girls faint. We used to just laugh; it was just a gig to us.

We go in and start to make records and we cut all the time. We cut during the week and then go out and play on the weekend with the rappers, then come back and record. Then along comes Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five and we’re doing all of their records and once they came, the Crash Crew, we did all of their records, the Funky Four Plus One, and so on and so on. We found ourselves just working all the time and that was a time when a lot of people weren’t working. It was tough times. We were post-Vietnam and post-recession taking place, 1977 -78. Huge gas lines and stuff like that. We were just on the flip side of that; we survived.

I look at one lane is us being together and going through this journey. The other lane was a reality of life, that this stuff is starting to make a mark. Every record we cut was a hit. It was back to back-to-back-to-back hits. Everything we touched was hits. I was one in the flocks of geese that were laying the golden eggs. I was happy to be able to make records and go into the studio. That being said, one lane was the fast lane of records and the other lane was, “How long is this really going to last? Is this just some novelty shit?” It wasn’t.

Disparity in credits for writing at Sugar Hill

Photo by Luciana Casado |

The disparity was the fact that I would write some of the songs that I wouldn’t get credit for them or credits were given to one of the Robinsons’ sons as a graduation present. For example, “The Message” was written mainly by Ed Fletcher, aka Duke Bootee. He wrote pretty much all of “The Message” except for the last verse. I came up with the melody. At that particular time, I was more than happy to participate. When we made records, it was almost like open-heart surgery was taking place. A lot of people were in there to make sure that the patient got transplanted. Whether it was the main doctor’s job, there had to be some RN’s there to make sure the room is sanitary and there had to be somebody that had to make sure the gear is working. So there was always a group of people generally working simultaneously on certain things. Sometimes your contribution, you just got used to not being put down [on the credits]. For example, Ed Fletcher, aka Duke Bootee, wrote the Message in its entirety and Melle Mel came in and wrote the last verse. It didn’t matter, that’s all fine, because Sylvia Robinson’s name is on that record whether she wrote something or not. That’s just the way it was.

Payment disparity at Sugar Hill

It’s like this:when you’re in a group of people and you operate as a group, and it’s time to get paid the money, it’s easier to tell 10 people “no” than one person. So the divide and conquer was alive and kicking. I had the opportunity to take the group hill or the record. I chose to take the group hill – not selling my friends out.

I’ve seen other people go to Sugar Hill, be wined and dined, taken to a steak house or a Japanese restaurant, and the next day they signed a record deal in one room as an artist and they went to another room and signed their publishing away, without even realizing what happened. It’s a crash course on reality. Yes, we were in the public eye, yes it was fun, and we were going all over the world. It was really, really exciting times, but I went home and looked at the reality of how I could raise my family with what I had. I was a dad at 19 and I still couldn’t make ends meet. I started off in All Platinum and we would record as studio musicians. I would have to record a lot of music to survive. When Sugar Hill came, we would start getting maybe a couple of hundred bucks a track. It still wasn’t in real time as what the rest of the world was getting paid. We were always on the back burner in a sense, but then again, we were ahead of the game, so you had these two things that were being stretched at the same time. Creativity and the friendship was our payment in a sense. We didn’t cross the line and try to get all cuddled up with the Robinsons and stuff like that, because we knew the game.

This is a familiar story; everybody shares the story one way or another. My story was probably not that much different than others in a sense, it’s just fast. We were the ones that were educated and raising these rappers, more or less. It was the band that was giving guys Music Business 101. We would draw a line in the middle of a page and this is publishing on this side, this is writing on that side. We would be like, “At the end of the day, you may be on the writer’s side, but it’s the publishing side that’s the one that is going to be able to sustain you throughout, year in and year out”. The Robinsons knew that we had that knowledge and they tried to counter by keeping us dormant and silent. We weren’t aggressive, crazy folks; we were smart enough to know how to tether ourselves to the different things. That’s how we dealt with it. We didn’t get confused by the illusion and we helped everybody, we never turned our back on anybody.

Recording for non-rap artists at Sugar Hill

Photo by Luciana Casado |

We cut for a lot of people. Not just the rappers, but also a lot of other folks came through. Sugar Hill acquired the Chess catalog: we recorded with Solomon Burke, Etta James, Wilson Pickett…people don’t know this!We recorded with Jack McDuff; I was in the studio with George Benson. Undocumented stuff! I can go on and on… there were a lot of artists. There were a few that Sylvia liked and they wanted to try to get back to their All Platinum roots.

With the success of what Sugar Hill did, it’s like a wave that just curls over. The hip-hop wave curled over anything that they had done prior. As much as they might have tried to push artists, people weren’t trying to make the All Platinum connection with the Sugar Hill connection. People were like, “I see the candy cane album cover – I know it has to be a hip hop artist”. Then all of sudden you’d see something that has Philippé Wynne on it or something like that and it tried to push stuff down somebody’s throat. It never really did anything. If they had gone with another label it probably would have, but that’s the nature of this business that we’re in.

We looked at it like, by working with all of those other people, it was a relief for us. We could actually do some other music and we’re not talking to kids anymore; we’re talking to adults.

The Tackhead Era

Prior to Sugar Hill, we had gone through “All Platinum University” and we graduated that with high honors and now we were in grad school, more or less. While we were in that grad school period, which was late 1978 to September of 79, we already started to prepare. We were looking at getting our own record deal, because we had already started recording and we were in the process of getting ourselves signed as a band. Then we got caught up in the tuna net at Sugar Hill and we realized that we had to put that on the back burner. What we did was, we took advantage of the studio time. For example, we went out and bought our own multitrack reel; they didn’t even know we were doing it. We took advantage of the system as the system was taking advantage of us. That prepared us for our endeavors that led us to the Tackhead era, the Adrian Sherwood era, the going to London era. That took place in the fall of 1984.

So we took all this energy, all those formulas, and we went to England. There we just continued with the knowledge and we were free to be able to go in with Adrian Sherwood. We knew how to make records out of nothing. We went through a complete shift. We started to really expand. Here’s this rhythm section that’s funky, that’s metal, that’s rock, that’s R&B, that’s blues, that’s country, all kinds of styles. It was nothing for us to go into the studio and somebody to say, “This might be the next Ministry record”. “Fine. Press record…let’s go”. We finally go into a situation where we didn’t have any handcuffs on. It was more like a body release…finally moving and we weren’t in a straight jacket.

We started our own label and only pressed up 1,000 of Tackhead “What’s My Mission Now”, but those 1,000 got out to the right people. Those 1,000 people that got those gave us the strength to do another record and press 5,000 next time. It was 2 different worlds:The world that we came from at Sugar Hill and the world we were dealing with in the UK. They were worlds apart, not just separated by water, separated by dark matter!It was worlds apart.

Tackhead was like the news with a beat. We were making anti-government records…in a nice way! Sometimes you have to get people on the dance floor to preach the gospel. We would take the piss out of some of these American reverends and preachers and make them famous, put them on records. Nobody gets more to the head than them. So we found a way to get away from the American scene. I’m American, I’m a Native American, so we never disowned our country or took the piss out of our hosts, but what we did is let everyone know we knew what side of the mountain the moon was hitting up on. We just held our cards tight and we let out the knowledge when it was needed, so we didn’t get deported! Or, when we tried to get back into America they didn’t send us to Guantanamo Bay!That’s kind of how we navigated.

We managed to get accepted by the English. The English are geniuses at winding up Americans; they do it just for fun. We found a way to not get wound up; we took that formula and came back to America and started winding the Americans up. This all came from making records and being free to make noise. Politics and all of the things that were going on is what opened me up and gave me the freedom to explore noise. It’s not just the music, it’s the politics, it’s the energy, the environment that I was in that was encouraging me to open up and be free.

Recording in the UK

Photo by Luciana Casado |

We were dealing with a new set of principles of how things are done in the UK. There were less distractions in the UK. We didn’t have TV on all night, everyone gets together and goes to the pub, there’s more of a social aspect. It’s the environment that they bring. There are more residential studios in the UK than any other place on earth. People knew how to make records. That’s why Hendrix moved over there, because he could have the freedom to experiment. In America there were still these guidelines:you have to make sure the bass drum’s EQ’d this way, and blah, blah, blah. That stuff got smashed in the UK. You had freedom to learn how to record, how to engineer, how to produce.

A lot of people in the UK didn’t know our hip-hop roots and it was damn sure that no one in America knew what we were doing in Tackhead. Our moment of separation from being that studio band to becoming an artist really took transition when we went to the UK. We started to come up with the idea of attaching a name to the 3 of us, the 4 of us with Adrian, whether it was Tackhead, which was the second name actually. The first name we came out with was called Fats Comet, then I came up with the name Tackhead and everybody liked it. We would make records and just pop a name on it, to see what was going on. That was the beginning of being able to move away from the back burner and get a little closer to the front burner.

All of that took place in the UK, because America had a different set of rules going on. [In the UK], you could bang a record out in the studio and put that jammy on a tape and go down to Camden Market and sell it! You could sell records out of the trunk of your car. It was a different vibe. You could get more of a return from pressing 5,000 copies than what you would have seen from your royalties on a record that sold 100,000.

It was almost like there was Doug Wimbish of the UK and I had a twin, someone in America that was playing to the American standards. On one level it was cool, but there was always room for improvement. America is a big country; the UK is a smaller island. You were dealing with island mentality. We learned America is a big country, it’s territorial. We were not going to Nashville and rocking the house. The UK, it’s different, it’s more centralized. You might have to work a little harder to make something, but once it makes it in the UK, everyone’s getting the same product.

Becoming “not just a bass player, but a sound system” in the UK

Photo by Luciana Casado |

That was the time when I had the opportunity to explore things. I had already started doing those things at Sugar Hill, but there were things that weren’t allowed or weren’t needed at that time. Then when I did songs like, “Vice”, which was used on the MCA Records “Miami Vice” record, which was a clear display of me playing every instrument on that. I programmed the drums, there’s no guitar, I just played distortion bass on that.

Adrian loved the crazy things, he would ask for low end frequency bass stuff as well, so I was encouraged to make noises, I was encouraged to make the bass sound like other sonics. That was when I was able to get those things released. Where we started to do recordings where, for example, Skip wouldn’t play guitar for one session and I would play bass and then play distorted bass to sound like a guitar. I was encouraged to do that. We always found ourselves in these minority segments that, nothing to do with race, but it was a small group of people that was listening to it. But that small group of people had loud voices.

I was able to explore, I was able to open up, I was able to put out my first single as a solo artist, “Don’t Forget that Beat”. I was playing more aggressive. Not worrying about the public. Run the red light!You’re on a highway and nobody’s there and you don’t have to stop. You’re in Idaho; you’re at the red light…there’s nobody there! There’s nobody for miles!You’ll get hit by a fly before you get hit by a car, but be respectful of what’s going on.

Widening Doug’s influence

We were starting to get the eyes and ears of the more mainstream. I’m meeting Mick Jagger, meeting Jeff Beck, meeting Annie Lennox, meeting Steve Lillywhite, meeting Trevor Moore, I can go on and on. Also, becoming involved in the music scene that’s already been there, adding another layer to the layer cake. You start to get these layer cakes going and it’s just what layer do you want to be on?I like the center of the cake as much as I like the icing with a cherry on top. We managed to layer ourselves wisely.

Vernon Reid, Will Calhoun, and the Living Colour beginnings

I had met Vernon in 1982 at a session that was being done for Duke Bootee, who had left Sugar Hill and got a solo deal on PolyGram. I produced a couple of songs for [Duke Bootee]. I wrote two songs, one of the songs was called, “Same Day Service” with a crazy bass line. I met Vernon is the studio when he came in with his guitar part. Fast-forward, Vernon would come by Keith’s place. We had a loft on 14th and 6th street in New York; it was like a musician’s sanctuary. We had no door bell, just come by and scream, “Hey, I’m here!” We would throw the keys down and you’d come up. Our place was a well-known place for musicians to come and hang out, one of which was Vernon. While he was putting together Living Colour, he would be hanging out, brainstorming and thinking about certain things.

Then we go to London. Vernon was a huge Tackhead fan; we’d do a Tackhead gig and he’d be at the gig before us with his guitar wanting to sit in. Adrian typically didn’t like the way he played, actually. I would get him to sit in, Adrian would turn him off. “It’s too busy!” Me and Vernon were mates. I start working with Mick Jagger and I was the one who told him about Living Colour. So we had a history, we were familiar with each other.

It was actually Will that called me for the Living Colour gig; it wasn’t Vernon. You know how they say things happen in three’s?I got a call from Bruce Springsteen, Seal, and Living Colour, all in the same week. Seal wanted me to be his musical director. With Bruce Springsteen, I got a call from his manager and she wouldn’t even tell me who the artist was. She said, “I have a business opportunity for you, but I’m not going to tell you who it is until I give you the spiel”. That was Bruce Springsteen at the end of the day. I always believe in, whoever calls you first to be honorable. So Will had called me, he was doing a drum clinic in the UK and he came over. He was like, “Either I’m going to leave the band or Muzz is going to go. One of the two of us. “That’s where it came down. Some things went down with Muzzy that they weren’t comfortable with so they decided to make a change. Still, I had to audition. Will was like, “I don’t know why you’re auditioning! I want you!”They’re auditioning Meshell Ndegeochello, T.M. Stevens probably, a bunch of cats.

They had one gig coming up and basically it was like Rock in Rio that was taking place in Brazil under a new sponsor. That gig was still on the books, and then they were going to make the “Stain” record. I fly into New York and I do an audition and that night and once again…there’s a hurricane! It was October of ‘91; I flew in just for this audition and flew right back. They still didn’t tell me I was a band member until after the first gig. I was offered the job to be in the band after the first gig that was in front of 80,000 people! There were about 3 days of rehearsal; it was really 5 days, but the band was so happy that they spent the first 3 days doodling around and just playing. Then I had to remind the guys, “Um, I need a set list! This is all great, but tell me: what are we doing for this one gig so I can focus on it?” By the time all the doodling was done, we had about 2 days to get it together. Next thing you know, I end up in the band.

Not working with the Rolling Stones

Fast forward to the end, Vernon’s going full force and he’s pretty much burnt out. Next thing you know, Mick Jagger is calling me up asking me to do the Rolling Stones record! They’re already auditioning bass players, they’ve already auditioned Darryl and Pino and a bunch of guys. I had already done Ronnie Wood’s solo record, I had already worked with Mick, and I played with Charlie after he hadn’t been playing for a while. So really, I just had to get Keith in the fold, plus I lived in England and knew the English mannerisms. So I went over to the UK and it wasn’t even an audition – we just started recording!They were like, “Yeah, we are going to start and we’d like you to be on the record”. I said, “When are you guys going to do the record?’Well, the record was going to take place in October and November and I’m like, well, Living Colour’s got an Australian tour. Mick was like, “How much is the band getting paid?”He was going to pay the band off for me to do that record!

The killer is this:like I said, Vernon was going through some really rough periods in his life. I was like, “Mick, if you want to do that, contact Vernon and let him know. We can probably pull this off” And Vernon, I don’t know if it was jealously or what, led Mick to believe that we were going to make another record. Meanwhile, he already had this plan in place to break the band up. So he kind of led Mick to believe we were going to do something else and that wasn’t the case at all. Vernon apologized to me after that, but that was my opportunity to go on working with the Rolling Stones.

And I’m still working with them [Living Colour]. Everything you do in life, you have to do it from the heart and have to be honest with what’s going on. You can’t let other situations derail you from what you’ve invested in. That’s the character that I am. That’s what happened and I can’t change it. Was I bitter? Yes. Was I upset? Yes. Did I get over it? Yes. Did I deal with it in a professional way?Yes. Did I sell my boys out at that time? No. Did I handle it professionally?Yes.

The bass community’s fear of advancement

For a bass player, there’s been this fundamental role that you should be playing. But it’s not just the bass player that should be playing the fundamental role; it’s the whole band. I’m not the timekeeper; the whole band should be keeping the time. At the same time, the bassist’s path has had many different chairs. It’s moved around. There’s been the time when bass is in your face – there’s your Jaco Pastorius’ and Stanley Clarke’s – all of my heroes. Bootsy Collins, Larry Graham, John Entwistle, Paul McCartney, Oscar Pettiford, Charlie Mingus, Scott LaFaro…I can go on and on about people who pushed these envelopes and made stuff happen.

It’s the beauty and the beast of the bass, is what I call it. You have the guidelines of what is a good bass sound; you have a community that preaches that gospel. I’m not in that community, never really been in that community. I’ve always been the outsider. I’ve been noisy. I’m in that community in some sense, I’ve done a lot of records, but when people see me with my pedals, they get nervous and think I’m a frustrated guitar player or something like that. All that I’m trying to do is still explore my voices; I’m still exploring myself.

Like when I was with Annie Lennox and I broke the whammy pedal out that I got from Joe Satriani. I was playing a line and she was like, “Whoa! I like that sound! That’s Annie Lennox! Can we put that on the record?”I’m like, “Sure!” That’s “Precious” on her “Diva” record. And I’m the first to play whammy bass on a major hit record from a major artist.

I got people familiar with a bass player playing with pedals. When a person sees the setup at first, they start laughing.Then when they see me use them, and I might not even use all of them, they come back with, “Oh, I see…you really use these things.” I say, “Well, you know, I’m not here for show-and-tell!” It’s being able to have the availability of changing your suit.

That’s my conversation; I play from the heart and from the soul. I’m not forcing anything down anyone’s neck. I go in sometimes and people will be like, “I thought you had a lot of effects” and I’ll say, “I’m the effect, plug me in!” When I do have those things, it’s for the music; it’s for the art of creativity. That’s where I separate myself from a lot of other folks, because I spent a lifetime learning all of these secret herbs and spices of how this pedal goes with that pedal and how to set that one. I have spent years to be able to find out how to make things sound.

People look at the bass as being flat and I look at it as being round. I don’t see it as a flat terrain that’s already been walked on, I see it as a wide, free, open atmosphere and everyone should be able to breath some of this air. I’m not the architect of this, I’m the recipient. I never really care what people think about what’s happening, I just know the effect.

Knowing yourself and sharing knowledge

Sonically, I’ve gotten to a level that I’m comfortable with. I’m comfortable with that level because I don’t let my ego get crazy. I’m always listening; I listen to what everybody does. I’ll get inspiration from school kids singing, I’ll get inspiration from a tabla player, I’ll get inspiration from somebody playing a calimba. My inspiration comes from hearing other people play their instrument and hearing the sound coming out. Sound is as important as the notes.

It’s the shape of the note that separates the individual. For example, you hear Victor Wooten play something, that’s Victor Wooten. I could hear 4 notes and know that’s Vic. I could hear Larry Graham and I could tell that’s Larry Graham, I could tell instantly. The shape of the note, the sound he got. How he dialed in and had the brains to get the right instrument with the right strings with the right amp and put the sequence of notes and put those fingers in the right place, that’s his print. Now, it’s easy to sit down at the dinner table and emulate someone else’s sound, that’s easy. We all take information from each other, but some people take this information and start to use it as weapons to make someone else feel like they are less of a musician. Share that knowledge!That’s your ego talking.

Then you learn how to brand the sound. We branded the Tackhead sound; we branded the Living Colour sound. It’s the shape of the note you use and that’s it. You can play all of the scales on Earth, which is great, but you still have to find your own fingerprints that are clear, that are you. Finding your own voice is where people struggle sometimes, because they are not listening to themselves. They’re listening to everyone else but themselves. That’s where the first conversation starts. You find yourself saying, “Why can’t I do this?” Well, did you allow yourself to do it, or did you take the advice of someone else? You might have been right at the beginning and trying to go some other place, but someone else was like, “Nah, I don’t like that. I’m going to be a musical police officer. That shit ain’t hip, don’t play that!” That’s the first step in the wrong direction to me.

All it takes is a moment to get inspiration. I’ll share with anybody anything that I know. I’m not one of these guys that turns his back when he plays a technique. If somebody wants to know how to play the flamenco slap, I’ll take my bass off, put it right around that person’s neck and say, “This is exactly how you do it”. I’m not hiding anything. It’s not going to do me any good when I’m out of here. The best gift in life is the one you give.

On the web:

dougwimbish.com

twitter.com/#!/dougwimbish

facebook.com/dougwimbish

youtube.com/user/DougWimbishBass

|

|