| |

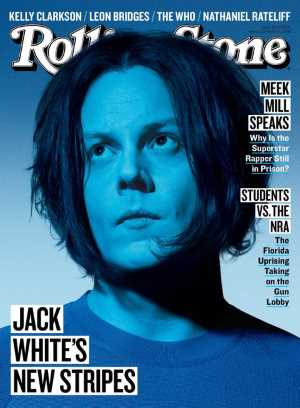

Taken from Rolling Stone (Mar 12, 2018)

Can Jack White Change His Stripes?

Jack White Cover Story: New Solo Album, Why White Stripes Won't Reunite

He became a rock legend by embracing the past. Now, the last guitar hero is trying to figure out how to live in the future

by Brian Hiatt

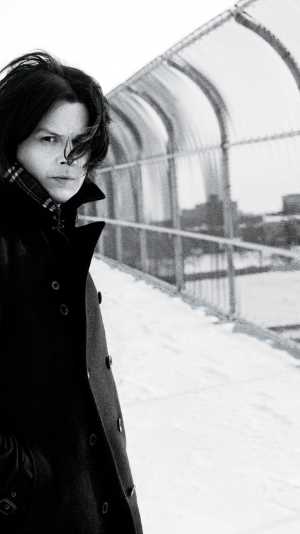

Pari Dukovic for Rolling Stone |

On a Detroit winter evening, years ago, Jack White punched a guy in the face. Really hard. And not just once, if you believe the police report. It was the culmination of a feud between two garage-rock dudes, back in 2003, when feuds and garage rock and dudes were still a thing. White has been known to hold a grudge; to send, from time to time, an intemperate e-mail; to, on occasion, "storm offstage," as online headlines would have it.

And he's not sorry, not at all. Yeah, he threw a punch or three. "Sure, but so did Johnny Cash," White says, leaning forward on an olive-colored upholstered armchair in his windowless, tin-ceilinged wonderland of an office, deep within the Nashville headquarters of his Third Man Records. Sitting on a bench behind him is a life-size skeleton with its legs crossed. White periodically strikes an identical pose, to distracting effect. "So did Sid Vicious. Jerry Lewis."

He lets out a disarming, high-pitched giggle, revealing an un-showbizzy arsenal of uneven little teeth, and corrects himself. "Jerry Lee Lewis. I'm sure Jerry Lewis too! If you call Johnny Cash's mom a whore in a bar, you expect him to not react? Or go push a Hells Angels bike over and see what happens. It's insane to do something you know is insulting to another human being and expect no repercussions."

So does Jack White have a temper? He told you once before, but it bears repeating. "With me, you get the extremes of every single emotion," he says. "Happiness, joy, jealousy, anger, excitement, passion, lust. And when you go into creative mode, it's definitely my job to not put any blockades up when emotions come to me. I'm sure if you interrupted, you know, Michelangelo while he was painting, and he got upset, I don't think anybody would argue with the fact that he has every right to be that way."

He's wearing black jeans, suede shoes and a snug long-sleeve T-shirt with an unusual, Star Trek-y collar. After a flirtation with a shorn rockabilly look, his black hair is back to the precise chin-length of his White Stripes days. Against the paleness of his skin, it looks almost like a special effect.

"I think a lot of emotions have been demonized over the years," he goes on, "as if they should never exist on planet Earth. Absolutely not. Without revenge and anger and these quote-unquote negative emotions, how would we have won World War II?" He leans back, takes a puff from one of the cigarillos he smokes, and ashes it on a lovely silver-and-glass ashtray.

Pari Dukovic for Rolling Stone |

Jack White is still willing to say stuff, even in an era when famous people are digitally disincentivized from uttering so much as a vaguely provocative syllable, where extremely cautious wokeness is the only sensible interview mode. He is untroubled by the sardonic tweet you may be composing right at this moment, and if it's not something you'd say to his face, he'd call you a coward.

Jack White is not a coward. He is, in general, unafraid. You can hear it on the album he's about to put out, the bracingly bonkers Boarding House Reach, which finds him, at age 42, making his most out-there music: gospel-Dylan backing vocals and jazz piano and drum machines and synths and conga breaks and spoken-word passages and jarring edits and a general air of wacked-out dada whimsy that reminds you that Captain Beefheart has always been one of his musical lodestones – an early promo shot of Beefheart and his Magic Band is one of the many treasures in White's office.

A point to consider: Jack White, here in midlife, is at the precise point in musicians' careers where we tend to most undervalue them. In 10 years, he will be an undisputed legend. So let's just jump ahead. Even if you're sure rock is dead (it's not), no one in this century has done a better job of jacking electrodes into its corpse, juicing it up and forcing it to boogie than Jack White. Not to mention creating the only guitar riff in recent memory to become a worldwide stadium chant. Based on the White Stripes' six albums alone – not to mention the Raconteurs, the Dead Weather, his solo work and an endless series of productions – he's more than earned a retroactive spot in the classic-rock canon.

Also: Old-school as he may be ("Mr. Old Timey," "Mr. Retro" are his own descriptors for the popular caricature), actual dad that he is, White isn't done evolving. He's still headed somewhere, still busy being born.

Pari Dukovic for Rolling Stone |

Jack White believes in making things difficult for himself. The artistic reasons behind this ethos are clear ("You have to have a problem/ If you want to invent a contraption," he once sang), the psychological origins of it less so. Catholicism? There is a picture, somewhere, of a little Jack White, at that point still Jack Gillis, meeting Pope John Paul II. White certainly has a self-flagellatory bent: "I'm bleeding before the Lord," he sings on "Seven Nation Army." Is it related to being the seventh of seven sons, and 10th child overall, with parents who were a little too worn out from parenting to set too many restrictions for their youngest kid? Probably. He considered, as a teenager, both the military and the priesthood, and ended up starting a company where employees wear uniforms – which no one seems to mind much, other than dry-cleaning fees.

At Third Man, White is his own label boss, and he half-yearns for an era when a big, square corporation would've stood in his way. "'Hey, the label won't let you do it,'" he says, fantasizing aloud. "'You can't record a song like that!' What cool problems to have! How easy to rebel against that and make something cool and new happen. But I'm coming up in the age of independent music where there are no rules, so I've always created my own constrictions." The White Stripes, of course, were all about what White once called "the liberation of limiting yourself." Though White stretched the boundaries over time, the band was, legendarily, built around a mere three elements: Jack's voice, his guitar, and his ex-wife Meg's oft-misunderstood, underrated, occasionally one-handed drumming.

But his rules sometimes seemed to border on masochism, if not pathology. White once told longtime Radiohead producer Nigel Godrich that he was mixing a Dead Weather album without automation, which meant he and an engineer had to nail every tweak in real time. "We would get two minutes in," White recalls telling Godrich, "and be like, 'Ah, fuck, forgot to turn on the reverb on the fucking vocal at the chorus – and now we start all over again.'" Godrich was aghast. The first automated consoles date back to 1973 or so; they are hardly digital witchcraft. "Why," Godrich asked, "were you doing that? Jesus, man!"

White couldn't quite explain it. "Because I just got to," he told him. "I got to know in my heart it was done the right way, the hard way, the difficult way."

But it was Chris Rock, who did a set in Third Man's event space last year, who really got under his skin. "Nobody cares how it's done!" Rock told White, in passing. He was joking, but not really.

"I wish he wouldn't have said that to me," White says, shaking his head, "because it's haunting my days. Because I've built my whole artistic creativity on this. But he's right, because nobody fucking cares! Even musicians don't fucking care. You know?" He describes showing "modern musicians" his setup – the tape reels, the vintage Neve recording console – to which they respond, "Well, I've got a computer." White bursts out with that laugh.

It can't have just been five words from Chris Rock. Maybe it's age, or restlessness. But White has begun to loosen his grip. "It became, 'I've got to let this go,'" he says. "This album is the culmination of, like, 'I don't care.' I want it to sound like this. I don't care how it was made." Which isn't to say he didn't set up a complex and arbitrary set of parameters for himself, because he totally did. He started by making demos in a rented apartment where he re-created his high-school-era four-track studio setup, taking pains to begin songwriting in his head, sans instruments. He went on to record in L.A. and New York with musicians he'd never met – some of them drawn from the live bands that back rappers like Kendrick Lamar. "Some of these songs have three or four drummers on them," says White, who, in the end, headed back to Nashville to "Frankenstein it all together," as Third Man exec and longtime friend Ben Swank puts it. "I don't know if he was feeling like he was in a rut or what," says White's engineer, Joshua Smith. "But it seemed he was feeling inspired by doing things a little different."

He tracked everything to tape, as usual, but for editing, White turned to Pro Tools, a digital convenience he condemned, not long ago, as "cheating." Moving to a realm where musicianship could be trumped by a click of a mouse was, he says, "a gigantic scary thing." Get behind him, Satan.

White also abandoned his long-favored pawnshop guitars. It started when he saw an interview with Eddie Van Halen, promoting his latest signature instrument, the Wolfgang Special. "He said, 'I wanted something that doesn't fight me,'" says White. "I was like, 'Those are the magic bad words that I completely disagree with. And that's why I'm picking his guitar.'"

So he sent Smith out to fetch one, and a 5150 amp, too, which led to the unlikely sight of White shredding through a few Van Halen covers. The amp didn't last, but he also got himself a St. Vincent signature model – "I love that she was making a guitar for women" – and a Jeff "Skunk" Baxter one as well. When he felt his fingers glide over the frets, he was dumbfounded. "Oh, my God," he says. "If people only knew how hard it was on these shitty guitars...because I didn't know!"

Just before lunch, White shows me an artifact from an old-timey mental asylum. It's the Alton State Hospital Review, a 23-pound scrapbook made by some of an Illinois sanitarium's 15,000 patients during the 1930s, chronicling their lives via prose, poetry, images and even tiny versions of rugs and dresses they'd sewn. "I'll be reading this the rest of my life," White says, flipping through with reverence.

And where does one obtain such an artifact? "This was a part of an auction," he says, vaguely. The next day, he hands me a driver's license that belonged to one Frank Sinatra, age 28 – another product of a winning bid. (It's fun, though perhaps not accurate, to picture these auctions as just White and Nicolas Cage sitting amid an auditorium of empty seats, outbidding each other unto infinity.)

Sometimes, buying this stuff yields artistic pay dirt. Last year, White purchased a musical manuscript written by Al Capone in Alcatraz (in the 1920s, even gangsters could read and write music) for a song called "Humoresque": "You thrill and fill this heart of mine/With gladness like a soothing symphony." Capone, it seems, played tenor banjo in a prison band with Machine Gun Kelly on drums. The song, a take on a Dvorák work, turns out to have been recollected, not composed, by Capone, but White still ended up recording it as the closing track on his new album. He's moved by the idea that a famous murderer had a weakness for such "a gentle, beautiful song." "It shows you, like, what we were talking about earlier," he adds. "Human beings are complicated creatures with lots of emotions going on."

White slips on an orange-and-black Detroit Tigers jacket and zips through Third Man's headquarters toward the one-car garage where he's parked his Tesla Model S. It's drizzly in Nashville. He's got the car's stereo tuned to a hip-hop Slacker Radio channel, per usual. He doesn't carry a cellphone, which means "freedom in a humongous way." It also meant he had to set out on foot in the winter cold the other day when he had a blowout on the freeway.

We zoom over to a parking lot near a farm-to-table restaurant, where he strides inside and takes a seat with his back to the wall. "When I walk outside," he says, "I'm assuming at all times that someone is about to touch me or say my name. It's a strange way to exist. It's like you're always on the defensive. Nobody has said shit to us in the last five minutes, but your brain is experiencing it, so it's almost like some caveman instinct. You're on duty, you're clocked in."

Inside Third Man Records in Detroit, MI. Photocredit: Peter Baker for Rolling Stone |

He orders a hummus appetizer and a salad of shaved Brussels sprouts with chicken. He's on a paleo-ish diet. He describes his exercise regimen as follows: "I run as fast as humanly possible, for short bursts." It's my turn to laugh. "It's true! I do! I'll run at top fuckin' speed...on a treadmill. I can't run outside. It's too dangerous to run that fast outside with rocks and shit, I'll probably break an ankle. But whatever the top speed on the treadmill, I'll go. For short bursts. So I don't have a heart attack or some shit." He thinks that's what human beings are meant to do. "You run as fast as you can to catch up with an elk. Then you hide for a couple of minutes, and you run really fast again."

Despite his caveman sympathies, he is, in many ways, a progressive. "Why don't you kick yourself out?" he sang, presciently, in 2007. "You're an immigrant too!" "America is learning that a two-party system is not a good idea," he says. "They're learning that their Electoral College is a ridiculous remnant of the past...that reality-television stars should not be looked to as equal to politicians...that a single human being has the ability to wipe out humanity. How ridiculous!"

White does mention a fondness for the controversial author and YouTube philosopher Jordan Peterson, though he's apparently only seen him talking about religion. "He's got more intelligence in his brain than his body can handle," he says. Later, I mention the anti-feminist, anti-political-correctness screeds for which Peterson is also known. "I didn't know about that," White says. "Maybe we should drop that whole thing now!"

When White was young, his parents stayed put in a changing Detroit neighborhood, leaving him one of the only white kids in his high school. "You really get perspective of what it's like to be somebody else who is a quote-unquote minority," he says. His brothers shared his love for rock & roll, but few others did. There were always instruments lying around his house, says Ben Blackwell, his nephew, a Third Man exec and longtime employee. "I have a distinct memory of being five or six years old and being walked through the parts of a drum set – and Jack walking me through the members of Led Zeppelin."

White does recall a missed opportunity or two in his neighborhood. Once he and a bassist friend, Dominic Davis, now a session player who's on White's upcoming tour, got "invited by this African-American kid in our class who played piano and saxophone. He said, 'Hey, man, I know these kids in your neighborhood, you should jam with them.' We went over, and these two Mexican kids are playing punk rock. But their lyrics were scary to me – they were talking about suicide, heavy shit I didn't know about. To this day, I'm like, 'Man, we should've started a band with those guys.' They were badasses. That was really strange, to be into punk in that neighborhood and be Mexican!"

White is, needless to say, full of eccentric passions. Early in our very pleasant lunch, with little preamble, he embarks on an 1,100-word-long rant about his "love-hate relationship with nurses" that deserves to be performed as a stage monologue. It begins with a kidney stone that emerged while he was driving in a van with Meg, and a nurse who shushed him when he was moaning with pain upon the arrival of a second kidney stone years later. "I just despise them and their trips that they're on all the time," he says, with still-fresh animus. "Like, I told this lady, 'How dare you tell me to be quiet when I am in extreme pain! You're supposed to be helping somebody who's in pain!' It's like talking to a cop. They hear so much bullshit all day long. They don't wanna hear what you have to say! You know, cops never look at you – always, like, lookin' around the room." For a moment, he does an excellent impression of a hostile, evasive, gum-chomping police officer. "They're controlling you when they do that." Anyway, he concludes, back on the nurse thing, "I don't know, man. I wouldn't want their job. They got a tough job, that's for sure."

If rock bands were closer to the center of popular culture, White might be even more famous than he is. Instead, he says, "I kind of slowly picked the most difficult spot to live in, which is in the middle," he says, back in his office. "It's easier to be a gigantic pop star or to be an underground band and be the underdog. Because the scrutiny comes from two different directions. There's people who want you to sound the same, there's people who want you to do something different, there's people who want you to be obscure, there's people who want you to be on the radio on the way to work."

He doesn't think superstardom would've agreed with him, in any case. "A majority of people in the pop world, they'd just make fun of the way I look," he says. "I mean, I can dig that I'm, for some reason, weird-looking for them. 'This guy looks like Edward Scissorhands! Like, what the fuck is this crap?'"

He once joked that he'd never achieve his "dream of being a black man in the 1930s." And while he's aware of "golden-age thinking," the dangers of "looking back at the past and only seeing the goodness of certain eras," he does sometimes yearn for the past. "I mean, the horrible racism and the treatment of gays and females in the 1920s is hard to forget," he says, "and at the same time you watch a clip of a musician playing in a club in Chicago and you think, 'Wow, why couldn't I have been born in that time period? And why couldn't I release my first albums when there was so much ground to be broken in the Sixties?'"

White is hardly the first successful white bluesman, and his thoughts on the idea of cultural appropriation are careful and nuanced. "There's definitely a family of musicians," he says, "and when you play with people of different cultures, nobody cares what anyone's skin is. Are there people who have taken advantage of other people's culture and made money off it? Oh, yeah. Black people invented everything. They invented jazz, blues, rock & roll, hip-hop, on and on and on. Every cool thing in music comes from them. And from the American South, their spread went global, which is absolutely one of the most incredible Cinderella stories of all time – this music being played on front porches in the Delta went global. Incredible. It makes you want to cry, it's so beautiful. And were there portions of people who wouldn't buy a Little Richard rec-ord but would buy the Pat Boone version? Of course." What really bugs him, though, is fake Jamaican patois. "The rhythm I'll let you get away with," he says, "but the fake accent? I can't stomach it."

White has become a vocal fan of hip-hop, and does something that's an awful lot like rapping on one of his new songs. There's a framed picture of Slick Rick on his office wall, not far from shots of Loretta Lynn and Iggy Pop. In his first decade of fame, White was publicly dismissive of the genre, despite a childhood that included whole bunches of it, with afternoons of blasting LL Cool J and Run-DMC while playing foursquare on Detroit streets. "A lot of that," he explains, "was my job as an artist. My role in my own brain is to not go along with the status quo, ever. At that time, digital was taking over...so of course it was my job to preach the idea of 'This is a person singing and playing an instrument. This is the blues.' I would just be like, 'Here's an unpopular opinion.'"

But he let all that go by the time he got in the studio with Jay-Z, circa 2009, and laid down a bunch of tracks for him, none of which yielded anything lasting, although versions of two of them finally pop up on White's new album. "I played a drumbeat and then I played a bass line," he says. "I played guitar and then he rapped over it." The fire-breathing riff of the new track "Over and Over and Over" dates back to the White Stripes, and White tried to record it multiple times over the years, including with Jay, who tried to give it the hook "under my Ray-Bans."

White's collaboration with Beyoncé, years later, was more fruitful. He gave her the track "Don't Hurt Yourself," which she reshaped into something fierce and personal – he was surprised and pleased when she used some of his demo vocals on the finished song. They've never performed it live together, though he was supposed to be on Saturday Night Live with her: "I'm not sure what happened," he says with a shrug. As White's camp recalls it, she also asked him to come up with an alternate arrangement for the Lemonade track "Daddy Lessons," which he did, with Third Man country artist Lillie Mae on demo vocals. Beyoncé had impressed everyone by requesting an arrangement á la roots singer-songwriter Seasick Steve. She didn't use it. "It was so cool," engineer Joshua Smith says wistfully.

White follows current music closely enough to have developed an amused contempt for DJ Khaled, especially after watching this year's Grammys performance of "Wild Thoughts," which draws heavily on Santana's "Maria Maria." "It's just Santana's song in its entirety," says White, embarking on an extended sarcastic riff. "It was nice of DJ Khaled to sit down and write and perform and record that – that was good of him! He's an incredibly talented man. There's no doubt about that. He does so much! He said, 'They told me I would never be on the Grammys.' Really? Like, 'Hey, man, like, I know you're headed to lunch, but I just wanted to let you know that you'll never be on the Grammys!'"

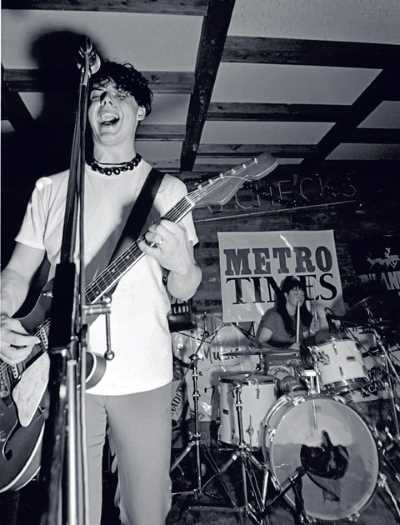

The White Stripes at Paycheck's Lounge, Hamtramck, MI, March 13, 1999. Photo by Doug Coombe |

When he's writing these days, White sometimes finds songs that clearly belong with a specific past project – the Raconteurs or the Dead Weather. And, he says, he holds those aside. But what if he comes up with a White Stripes song?

He laughs, a little too hard. "That doesn't really happen too much," he says, and pauses. "I'm not telling people what to think about the White Stripes. They can think whatever they want about it. But there is a case to be made that in a lot of ways, the White Stripes is Jack White solo. In a lot of ways." He says this very casually. "There's only two people in the band. I was writing and producing and conducting. The melodies are coming from one person, the rhythm is coming from Meg. People define things by the label you give them. I'm sure if Billy Corgan called his solo album Smashing Pumpkins, it probably would've sold twice as many copies or whatever."

I ask if there's any chance that the White Stripes, who broke up in 2011, could be revived. He squints, as if the question is odd. "I highly doubt," he says, "that would ever be a thing."

White doesn't think he'll get married again, either. "As an artist, it's very difficult for me to have regular everyday-life things." He's raising two kids with his second ex-wife, and he took time off from touring the past few years to spend as much time as he can with them while they're "in their single-digit ages."

He sometimes wonders if his intensity is out of place in modern music. "I'm fucking pushing myself constantly," he says. "Sometimes onstage I'm like, 'Why the fuck am I bothering? Why am I pushing myself so hard?' The next act on the festival is playing the same set they played the night before in the same way and having a blast. And I'm sweating bullets and bleeding all over the stage. It's hard to know if it's worth it."

He recently saw a Bruno Mars live clip that made him think. "He said something a lot of artists say: 'I hope you guys are having fun tonight.' It's the simplest thing in the world! I've never said that and I don't know how to say that and I don't know what that would mean." He blinks. "Is that really why we're here?"

Instead, White thinks it's all about "the truth ... trying to get somewhere real," he says, stretching in his chair. "Your ideas were pure and you were trying to sculpt sound, trying to make something beautiful."

Thus far, he's always had the next thing lurking in his head. "I haven't had that moment yet, of 'I have no inspiration, I have no idea what to do tomorrow.' A little part of me wants that writer's block, just to see how I could overcome that challenge. But another part hopes it never happens."

Earlier in my visit, there was a knock on the door. "Someone has a summons for you," a voice says. It's Blackwell, the Third Man exec, and he has actually brought the first three vinyl copies of Boarding House Reach. "Ahhhh," White exclaims, grabbing a copy and looking hard at the indigo cover. (The androgynous person on the front has White's eyes: "When you cover up the eyes or the mouth, the figure changes gender.") "It turned out good, man," he says, tearing off the shrink-wrap. "They tell me the test pressing sounded incredible." He looks at it again, this beautiful object he brought into the world, and smiles. "It exists now," he says.

|

|