| |

Taken from Rolling Stone (January 29, 1987)

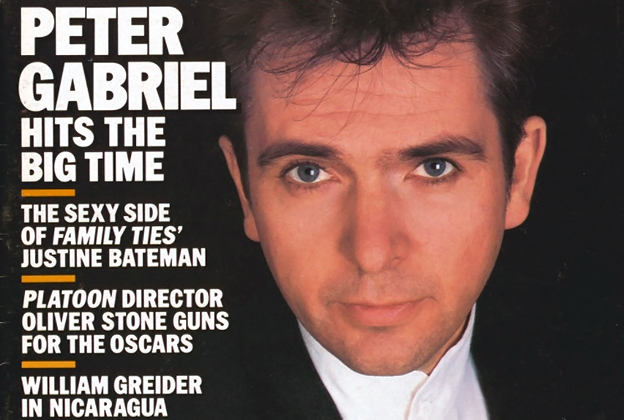

Peter Gabriel Hits the Big Time

Over ten years after he said goodbye to Genesis, Gabriel has finally made it on his own

by Steve Pond

Peter Gabriel on the cover of Rolling Stone.

Robert Mapplethorpe |

'What's a god like you doing in a place like this?" That's the title on the note a flight attendant delivers to Peter Gabriel, who's just about to tear into his second bag of smoked almonds as he flies from Salt Lake City to San Francisco. As Gabriel reads the impassioned, page-long poem from an anonymous passenger, his face is expressionless; when he finishes, he cracks a slight smile.

"I get a lot less of this these days," says the singer, songwriter and technological wizard, who has long been the idol of a sizable and devoted cult. "I used to get quite a few letters from people I visited with my psychic body or told to do all sorts of things with a song."

He shrugs and fiddles with the torn bag of nuts. "I still find that cute," he says.

Peter Gabriel may run across fewer head-over-heels fanatics nowadays, but he's also recognized on airplanes, in hotel lobbies and elsewhere far more often than ever before. Last year was the year cult stardom suddenly turned into something bigger, wilder and more profitable, the year everything worked: he had a Number One hit with the chugging rhythms and florid sexual metaphors of "Sledgehammer"; he turned heads and altered his once cold, artsy image with the cockeyed exuberance of the accompanying video; his sets were a highlight of Amnesty International's Conspiracy of Hope Tour; and he had a best seller in his album So, a joyful, moving and unexpectedly personal response to his public concern for social ills and his private despair over marital problems.

So as he wraps up a three-day ski vacation in Utah and heads to California for the last four shows of his American tour, it's fitting that Peter Gabriel has just released the deliberately cartoonish, outlandishly boastful "Big Time" as a single. The big time is precisely what this is.

On past tours, Gabriel filled medium-sized halls with hard-core Anglophiles, techno-freaks and fans of artsy innovation, plus the odd mainstreamer attracted to "Shock the Monkey" or "Games Without Frontiers." That audience, says Gabriel's guitarist, David Rhodes, used to consist of "denim guys and intellectuals." Now the crowds are larger and younger, and they include lots more women – some of whom even scream at Gabriel's clunky but dramatic moves, aptly described by his keyboardist, David Sancious, as "dancing by intuition."

From his favorite airplane seat – nonsmoking, on the aisle, near the front of the cabin – Gabriel considers his new audience during a characteristically long pause. "I think," he says slowly, "that as I enter my midlife crisis, it's exactly what I need."

Peter Gabriel, rock star at age thirty-six, budding sex symbol by virtue of his close-cut dark hair, vivid but melancholy blue eyes and sly but cherubic grin, allows himself a quiet chuckle. "Yeah, it brightens up the days a little bit."

It started with a video. It started with singing vegetables and dancing chickens, with model trains circling Peter Gabriel's skull as he sang about lust in a series of luridly silly metaphors. "It was extremely uncomfortable sometimes," he says, sighing, of the eight painstaking days it took to shoot "Sledgehammer." "Lying down under a plate of glass, with a sort of metal rod supporting the back of my head, and fish and fruit being moved around." He grimaces. "The fruit smelt all right after a few hours under the lights, but the fish stank."

It was instantly labeled the most innovative video on the air, but that was to be expected from an artist with a longstanding reputation for hightech experimentation. Crucially, "Sledgehammer" was also one hell of a hoot. "I think the song would have fared okay,' cause it did seem to work well on the radio," says Gabriel. "But I'm not sure that it would have been as big a hit, and I certainly don't think the album would have been opened up to as many people without the video. Because I think it had a sense both of humor and of fun, neither of which were particularly associated with me. I mean – wrongly in my way of looking at it – I think I was seen as a fairly intense, eccentric Englishman.

"I never really thought of myself in quite the way that I think other people do," he continues. "I do have quite a lot of fun with some of what I do, and I don't think that always comes through. But I think it did on this record and in the video. And that, if you like, got people interested in checking out the album, to see if they liked it."

It's the afternoon of the first of his two Oakland Coliseum shows, and as he sits in his San Francisco hotel room, Gabriel does seem fairly intense and, maybe, a touch eccentric – though in a relentlessly low-key way. Perched on the sofa, in a red-and-gray-patterned shirt, baggy black pants, black loafers and white sweat socks (the only clean socks he's got left), he speaks softly and hesitantly, often apologizing for his reticence. His gaze is direct, his face placid, contemplative and earnest; meanwhile, his hands fidget, and his legs tap out a steady beat under the coffee table.

Mainly, he seems like a nice guy. In Los Angeles, he bypasses his favorite hotel, because others in the band want to stay someplace else; in Utah, when a guest excuses himself to find the men's room, Gabriel instantly jumps up and walks halfway across the dining room of the ski lodge to point the way.

"The strangest part about it is, he's like a mensch," says Gary Gersh, a Geffen Records A & R executive who stayed in close touch with Gabriel during the making of So. "I mean, he's just a sweetheart in the classic sense."

"He can be stubborn, but it's never in a very noisy way," says David Rhodes, who has played guitar with Gabriel since the singer's third solo album. "But he always gets what he wants. He holds out for things – which, I think, is why people are responding so well now, because he's held on to his key beliefs and hasn't sold himself down the line."

Partly, it seems, Gabriel is a thoughtful artist who extensively researches songs like "Family Snapshot" (about a political assassin), "San Jacinto" (about Indian initiation ceremonies) and "Mercy Street" (based on the work of the late poet Anne Sexton); a craftsman who spends months on his records, reshaping the lyrics and the arrangements; a strict vegetarian who owns an isolation tank and is fascinated with all sorts of emerging technologies.

And partly, he's a dry wit, who says he titled his album So because it "has a nice shape but very little meaning." While recording the album, he, Rhodes and coproducer Daniel Lanois dubbed themselves the Three Stooges and would often don yellow hard hats and dance wildly to "Sledgehammer."

"There may be three levels to me," says Gabriel himself. "Level one is a fairly amiable, easygoing person. Level two is a bit darker and determined and perhaps a nastier piece of work. And layer three is a naive little boy. I think I can see all those three at work in different areas, and we all need to allow them to come up for air, to find a place where things aren't being hidden or suppressed. Which is something" – he grins ruefully – "that the English are remarkably good at doing."

The sixties soul sound of "Sledgehammer" may come as a surprise for fans accustomed to thinking of Peter Gabriel as an esoteric art rocker, but for Gabriel it's a return to his first love. When he became interested in music more than twenty years ago, R & B was his passion, Otis Redding his hero and the drums his instrument – all factors that made him stand out on the English farm in Woking where he grew up and at the strict, centuries-old "public" school (in America, a private school) where he first met the friends who became Genesis.

Gabriel's father was an electrical engineer and parttime inventor who came up with an early version of cable TV, read avidly and was eccentric enough to get off the train from London, stand on his head and do a few minutes of yoga. His mother, meanwhile, played music, as did her four sisters. Peter grew up with "piano lessons, dancing lessons, riding lessons, every sort of lesson."

As a kid, though, his interests lay elsewhere. "My favorite thing on the farm," he says, "was to build a dam across the river and build a central circle in the middle of the dam, in which I'd build a fire. Then I'd sit on the bank and wait till the water was high enough to wash over the fire. I'm sure some shrink would have some meaningful analysis for all this."

One of the few boys in a farming community with plenty of girls, he was also "free of inhibitions at that age" – then puberty hit. He grew chubby and became shy and withdrawn; things only got worse when he was sent to Charterhouse, a prestigious, conservative boys' school outside London.

"We were both pretty unhappy there," says Tony Banks, Genesis's keyboard player, who became Peter's closest friend at Charterhouse. "Neither of us liked being away from home, and the restrictions got us down more than they did most people. You weren't allowed to walk through certain doors or across certain bits of ground or have certain buttons undone. So we both got into people like Otis Redding and into the idea of playing music. Technically, you weren't supposed to have record players or radios at school, either, which was one of the reasons it was so exciting."

While at boarding school, Peter met his wife, Jill Moore. He was sixteen; she was fourteen. He was the first boy to arrive at a dance near Charterhouse; she was the daughter of the queen's private secretary and, he says, "the prettiest girl in the room – so it was quite simple." They were married when he was twenty-one.

Peter played drums in a soul and jazz band ("He always had the idea of the beat, but he didn't quite have the coordination," says Banks), then formed Genesis with Banks and two other Charterhouse students, Mike Rutherford and Anthony Phillips. They slowly attracted attention – partly because of their increasingly lavish, eclectic brand of late-Sixties and early-Seventies art rock, partly because Gabriel, their lead singer, took to telling long stories and wearing flower costumes, fox heads and red dresses. The latter two, Gabriel happily remembers, made their debut at a boxing ring in Dublin, "not the most tolerant place for men in ladies' dresses."

There was, Gabriel says, a "great sense of liberation." But he never fully participated in the abandon of those times: "The only drug I was interested in was acid, but I was too frightened by my dreams in regular hours to contemplate that. 'Cause I had very vivid dreams as it was, and I think I was fearful of letting go of control."

Instead, he had two experiences with hash. The first time he giggled a lot and then threw up. The second occurred about five years ago, when Gabriel, ever the diligent researcher, went into his recording studio, ate a lot of hash cake and then sat down at a desk with his notebook and tape recorder. Nothing happened, so he ate a lot more. Then he leaned his head over the desk and felt "these two bolts of metal shoot up the back of my neck, like mercury in a thermometer. They came crashing round the front of my head, and I thought, 'Uh-oh.' And panic began to set in deep."

Convinced he was going to die, he headed for home. "I decided I would try and get home in time to say my last words to my wife and kids. It was about half a mile across fields to where I was living, and I was still carrying the tape recorder, so there's this very funny tape of me thinking that I was going to die. I was sort of getting revelations, as I approached my death, about the meaning of life. I was certain that life was actually organized into five videotapes, which were all running slightly out of sync. And very soon after I came upon this profound piece of wisdom, you hear me collapse into a ditch."

Eventually, he found his way home, where he had milk with sugar and went to bed. "My wife thought I'd been in a road accident," he says and then breaks out laughing. "The strange thing was, my kids didn't think there was anything different."

Genesis was big stuff – and, as is true today, The lead singer got most of the credit. In 1974, Gabriel got an offer from movie director William Friedkin, who asked him to contribute to a proposed film script. Gabriel took a week off from working on the Genesis album The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway. The band wasn't happy, and, he says, "the rot began to set in."

"Genesis, at that time, were not into anyone having extracurricular activities," says Gabriel, adding slyly, "unlike today.

"And there was also a certain jealousy, because as frontman I was being credited as sole creative source of the band, which was really unfair. There were various transitions taking place within the band and within my life – such as the birth of my first child, which was far more important to me than finishing off a Genesis record."

That child, Anna, was born in 1974. She had caught an infection in the womb, and her umbilical cord was wrapped around her neck. She was born feverish and starved for oxygen, with her lungs full of fluid that she had swailowed in the womb; the doctors were so convinced she would die they wouldn't even let her mother see her for a week. (She recovered, and today she is a healthy twelve-year-old.)

"That was a major drama for me," Gabriel says quietly. "My wife remembers it that before the birth I was away with the band all the time. The band remember it that I was away with my wife all the time. I think it was the cause of bad feelings, because I was the first one of the band to have children, and until you have kids you have no real understanding of the emotional experience that it is. Let alone something going wrong."

"The birth changed him quite a lot," says Tony Banks, "and it was difficult for us to accommodate that, because at that stage in the group's career, we still wanted to do as much touring as we could. And after he wrote ninety-nine percent of the lyrics on The Lamb, I think he felt that he would never get that chance again, that we wouldn't let him do it.

"I tried very hard to persuade him not to quit the band, but he's not quite as taciturn when it comes to people he knows well. He gets a certain set look, and he is obstinate. So he left."

Disgusted with the music business, Gabriel puttered in his garden and wrote songs and shaved his head. "It was a fun thing to do," he says, shrugging. "I just shaved my head because I hadn't tried it before. And I think it's a good experience for everyone." Within a few months, his wife did the same – not for fun, but as an act of penitence for having been unfaithful. "I think at the time it was partly that she didn't like herself," he says, "and she wanted to make a bold gesture."

The Gabriels had another child, Melanie, and Peter Gabriel's solo career got under way in 1977 with an album that mixed orchestral flourishes with raw rock & roll; the songs ranged from apocalyptic visions ("Here Comes the Flood") to an allegorical account of his leaving Genesis ("Solsbury Hill"). His second album, released the following year, was a denser, more forbidding and, he thinks, somewhat unsuccessful collection produced by Robert Fripp and partly designed as a deliberate reaction to the pop-oriented debut.

Then what Gabriel considers his breakthrough came, when he simultaneously discovered African music and drum machines. Turned on by the new rhythms and the new tools, he wrote a batch of tunes that included the chilling "Family Snapshot" and "Biko," the soaring ode to the murdered South African activist Steve Biko. Gabriel's label, Atlantic Records, refused to release an album that it considered not only uncommercial but bad. Atlantic dropped him – "quite a knock to take when you've just put a lot of time and your guts into almost a year's work, and you think it's the best thing you've done." Mercury Records picked the album up, and "Games Without Frontiers" became a hit. "Fortunately," Gabriel says, grinning, "Atlantic's regretted it."

After that album, he signed with Geffen Records and explored third-world rhythms and textures even more fully on his next album, the fourth consecutive LP to be titled Peter Gabriel (except in the United States, where the company put a sticker on the cover that said Security). With a solid reputation as an innovator, Gabriel finally felt free of Genesis.

"It took about six years, really, before I was considered as a separate entity with separate tastes," he says. "It's frustrating, I think, if you perceive yourself as doing something quite different, which I think I was, and still get branded by the same brush. That particularly applies in England, where having been ex-public-school, middle-class and ex-Genesis switches off the majority of the media before they've even heard anything."

Now it doesn't bother him, Gabriel says, though he's well aware that his replacement as Genesis's lead singer, Phil Collins, achieved huge solo success with the help of a drum sound pioneered on the third Peter Gabriel LP. Sure, the old comparisons sometimes come up – say, when Gabriel is reminded of the version of Marvin Gaye's hit "Ain't That Peculiar" that he performed during his first solo shows in 1977.

"I'd like to do something like that again," Gabriel says, chuckling softly. "But I couldn't do a Motown song anymore, because they'd say I was copying Phil."

Sitting in the back of the minibus that's taking him to the Oakland Coliseum, Gabriel looks out the window at Christmas shoppers crowding San Francisco's sidewalks. "I got a little shopping done, but not enough," he says, grumbling. "I'm trying to find something for my kids to give to my wife, because they're not usually very good at coming up with anything on their own."

The unsuccessful shopping trip notwithstanding, the fact that Gabriel is taking presents home to his wife and kids is a sign of progress – because for about eighteen painful months not long ago, he was separated from Jill, Anna and Melanie. "I think this is probably the most positive record I've made, in some ways," he says slowly. "And, um...it's a little bizarre in some ways, because it came after one of the worst periods of my life. But maybe I needed to get some playful energy in there....I think it's easy for me, sometimes, to immerse myself in my work and sort of divert energy that perhaps should be going into personal things."

So when he wrote the love song "In Your Eyes" or the images of guilt and redemption in "That Voice Again" and "Red Rain" or the despair-versus-hope dialogue of "Don't Give Up," Gabriel was undergoing professional and personal changes. "I wanted some of this album to be more direct," he says. "Over the past few years, sort of, I tended to hide from some things, both personal and in my music. And so, if you like, it was part of a coming-out process."

Gabriel opened up and stopped hiding his emotions partly through est (hates how it's marketed but likes how well it worked), partly through a couples' counseling group he attended with Jill. After est, he hugged his father for the first time in more than a decade. Now he also finds it much easier to express anger, "which I've always been nervous of'; now he and Jill are on firmer footing.

"With relationships, for me it's always a case of a work in progress...," Gabriel says, "but we've been living back together again for maybe a year now. And there's still work to be done, but we do really well now, and hopefully we'll sort it out. Part of the problem, I think, is that you're very different people at sixteen and fourteen than you are at thirty-six and thirty-five, so, um...there's a certain amount of growing pains."

The fact that some of those growing pains are reflected on So is one of the reasons Geffen Records is so happy with the album. "Throughout the years, I didn't really know who the man behind the mask was," says the label's Gary Gersh. "With this album, part of the idea behind our whole marketing campaign was letting people know that there really wasn't a mask anymore, that the man was actually touchable. You can listen to the record and get inside his emotions."

There's one subject that touchable man finds himself returning to again and again, and with a little prompting Gabriel locates it. "There is some sense of, uh...," he says, then pauses for a long time. "Alienation is a common theme, which is the struggle to break out of a sense of separation."

And has that been a struggle in his own life?

"Yeah, I think so," he says, and his voice gets even softer than usual. "Definitely."

"Can we turn the lights off in this van?" asks Peter Gabriel, and it's a reasonable request when you consider that he's not wearing any pants. The second Oakland show has just ended, and he and the band have run straight to the minibus, which is now making a mad dash across San Francisco Bay to catch a midnight flight to Los Angeles. The vehicle is a de facto dressing room – but the Coliseum parking lot is full of gawking Gabriel fans, and it wouldn't do to have the star mooning his audience. So the lights are shut off, the band towels off and changes, and they head for the Bay Bridge.

Buzzing with adrenalin from the show, everybody is in a loose, playful mood, passing around the Christmas gifts that promoter Bill Graham put in their backstage stockings: candy, yo-yos, confetti poppers, leis. Gabriel ranges up and down the aisle taking drink orders; when the minibus hits a bump, and he dumps much of his Heineken onto his shirt, there's boisterous laughter from Rhodes, Sancious, bassist Tony Levin and drummer Manu Katché.

On the plane, things calm down a bit, though Gabriel leaves his bright-yellow lei in place as he unwinds a long black scarf from around his neck. Settling into the front row, he declares himself satisfied with the night's show, a bracing and moving piece of rock theater. Using spare but haunting lighting and the expressive body language he has been perfecting for years, Gabriel played the part of an individual struggling for human contact in the face of inhumanity, social evils and dehumanizing technology. But the show was also more fun than most of the performances on his previous tours, and it climaxed with a joyous duet between Gabriel and the Senegalese singer Youssou N'dour.

It ended with the somber strains of "Biko" – and a chance for Gabriel's fans to see the determined activist, who spends much of his time working for human rights, who regularly visits Central America, who roundly denounces American policy there: "By ignoring the needs and rights of ordinary people, the U.S. is alienating not only a lot of Central and South America but quite a lot of the third world, quite needlessly." But instead of preaching, Gabriel simply asks his crowds to participate. That means the fans sing the end of "Biko" themselves: that means Gabriel falls into the audience during "Lay Your Hands on Me" and expects them to pass him over their heads rather than tear him apart.

That backward flop into the audience has been a staple of Gabriel's live shows for years, and it gets riskier as his audience gets bigger. But he insists on keeping it in the show – a decision, says everyone around him, that's completely in character for a guy who simply isn't changed by fame and fortune.

"My lifestyle hasn't really changed," Gabriel says, shrugging. "I've lived comfortably for five to seven years now, but I still look to save a few pennies here and there, because that's a very hard habit to get out of." He has no plans, he says, to move out of the quiet English community in the Cotswolds where he lives. Nobody there makes a fuss about the resident pop star unless he's on Top of the Pops.

But he does want new video equipment and an upgraded studio, and he wants the time to experiment by making videos for all the So tunes not yet turned into clips. He would like to mount a performance-art piece and tour smaller halls next summer. And he's still interested in the idea of an alternative park that would be "a mixture of amusement park, art gallery, university and holiday camp." It combines many of his current fascinations: high technology, behavioral research, environmental and interactive art. Plus some old-fashioned thrills, courtesy of the author and psychiatrist R.D. Laing, who has talked with Gabriel about a Ride of Fears, in which the most common phobias would be presented with increasing intensity until the rider conquers them all or pushes a panic button.

And would Gabriel make it through without pushing that button?

"I don't know," Gabriel says, laughing. He once learned to control a fear of snakes with the help of a friendly python. On the other hand, he says, "when I was skiing, I got to the edge of a cliff and experienced vertigo, went to jelly."

The mixture of science and entertainment seems typical of Gabriel, who's certainly got the only rock & roll tour program that includes an Anne Sexton poem, a conversation with a signing gorilla, photos of artwork done by mental patients, a child's letter to God and pitches for Amnesty International and the University for Peace (a Costa Rica-based organization for which Gabriel and Little Steven Van Zandt organized recent benefit concerts in Japan).

Near the front of the program, there's a picture of Gabriel making a funny face and a caption that reads, "How did I get this far?" But now, as he heads to Los Angeles for the final two nights of his most triumphant American tour ever, he seems satisfied rather than surprised.

"People can put it down to luck, or good fortune, or..." He trails off, his face barely visible in the darkness of the cabin. "But I don't think you succeed by accident."

Ahead, Los Angeles is waiting for Peter Gabriel: there, the fans will pass him above their heads until he's halfway back in the huge hall, farther than any other audience has done on the tour; there, Sting and U2 have been calling for tickets to the shows; there, Joni Mitchell and Don Henley and Robbie Robertson will show up at the Forum, outside Los Angeles, and later at a party for Gabriel thrown at a trendy West Hollywood restaurant.

It sounds like a line from Gabriel's new single: "I'll be a big noise with all the big boys." This is Peter Gabriel's big time, and for a minute the way he introduces the song onstage sounds more appropriate than ironic. "Once upon a time there was a man from a small town," he says. "But he had big, big, big ideas."

This story is from the January 29th, 1987 issue of Rolling Stone.

|

|